Bob Ford was the man who killed Jesse James, who is considered one of America’s most famous bandits. The killing of Jesse James was considered a cowardly act and Bob Ford’s actions followed him for the rest of his days.

Story by Ron Soodalter

St. Joseph, MO: April 3, 1882. Jesse James was uncharacteristically careless in trusting the Ford Brothers, Bob and Charlie. As the bandit leader almost certainly knew from recent newspaper reports, one of his band had already betrayed him and turned state’s witness. He was on the run. Yet, he welcomed the Fords to his rented hilltop hideout, fed them, and discussed with them his plans for a raid on the Platte City bank. After dinner, he divested himself of his pistols and climbed onto a chair, ostensibly to dust or straighten a picture on the wall, whereupon 21-year-old Bob Ford shot him in the back of the head with the same .45-caliber Colt revolver that Jesse had once gifted him. Trailed by brother Charlie, Bob then ran down the hill to the telegraph office to inform the Missouri governor of his deed.

It is safe to assume that every student of western history is familiar with one or another version of this story, which continues to be told in books and on film. To this day, Jesse James remains America’s most famous bandit. Photographic prints showing him laid out in his coffin sold in great numbers and are still treasured by collectors today. The fate of Bob Ford, however, is not so widely known.

Robert Newton Ford was born in Ray County, Missouri, near Richmond, in 1862, and grew up hearing about legendary Confederate guerrilla and bandit leader, Jesse Woodson James. While his older brother Charlie became a belated member of Jesse’s gang, Bob was more of what one historian referred to as a “hanger-on,” apparently content with running errands and performing chores for his idol.

Then, in 1882, things changed for the 21-year-old acolyte. During an earlier dust-up, Bob had reputedly slain Wood Hite, a close cousin of Jesse’s. He knew that Jesse had recently killed two gang members he suspected of disloyalty and would not hesitate to dispatch him.

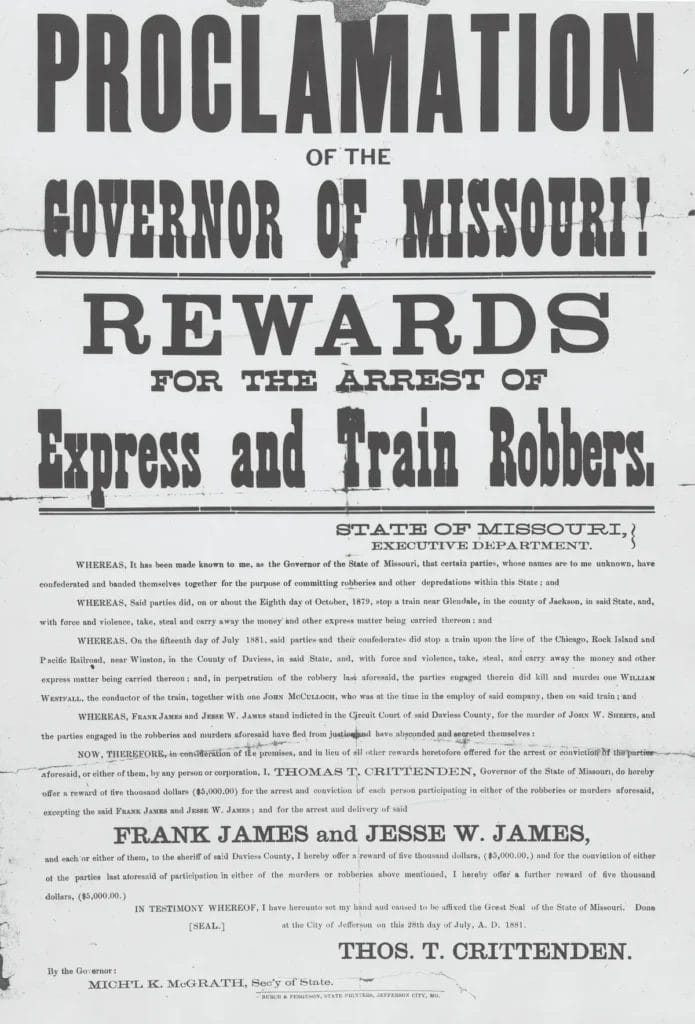

Greed also played a major part in Bob’s decision to betray his hero. Recently elected Governor Thomas Crittenden offered a reward of $10,000 for the outlaw’s capture, to be paid by the railroad companies that had long suffered at Jesse’s hands. The amount was massive for its time, worth nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Bob was determined to have it. He invited brother Charlie to join him in conducting the assassination.

Wood Hite’s slaying set Jesse’s demise into motion. The authorities, it seems, were most interested in talking to Bob regarding the slaying of Jesse’s cousin. He was brought in for questioning, but captured the attention of both the governor and various officers of the law when he assured them that he could deliver Jesse into their hands.

Bob subsequently met in secret with the governor. If properly motivated, Crittenden—who was desperate to put an end to the James Gang—was in a position to set aside all charges. In exchange for the death or capture of the bandit chief, he promised to absolve the brothers of any wrongdoing relating to the slayings of both Wood Hite and Jesse James and to pay them the reward.

Photo Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri

Once the deed was done, Bob and Charlie surrendered to the law, only to find themselves charged with first-degree murder. They were quickly tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged. The governor, however, was true to his word, and within hours of the sentencing, pardoned them both. The railroads paid the reward, which was divided among the Fords and three law enforcement officials. The Ford brothers’ take was considerably less than they had anticipated.

Life for Bob Ford was about to become something of a nightmare. Jesse James had captured the imagination of the average citizen, who saw him not as a coldblooded thief and murderer, but as America’s Robin Hood. There would be scant tolerance for his slayer. For the rest of his brief life, the young assassin discovered that wherever he went, he was characterized as a contemptible back-shooting coward.

In fairness, while it is true that Bob Ford shot Jesse from behind, back-shooting in the Old West was more common than many Americans are willing to accept. The fact is there were practically no “showdowns on Main Street,” in a culture where killing an enemy was more a matter of seizing the advantage than of fair play. Some of the country’s most notorious pistoleers, including Wild Bill Hickok, John Wesley Hardin, Billy the Kid, and Morgan Earp were dispatched from behind, from ambush, or in a dark room. The logic was unassailable: Why give a man, especially one who is well-versed in the use of firearms, better-than-even chance to slay you, when all doubt can be removed from the equation by simply lying in wait for your foe?

Photo Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri

Initially, Bob earned money by posing for photographs, in some instances holding the actual weapon he had used to dispatch his leader. There was little money to be made, however, and the brothers hit upon another way in which they might earn a living. They literally took their show on the road, in a staged reenactment of Jesse’s slaying titled “Outlaws of Missouri.” Neither was a natural actor, and the audiences were uniformly hostile, constantly interrupting their performances with catcalls, insults, and objects thrown at the stage.

Charlie outlived Jesse by only two years. In May 1884, depressed, suffering from terminal tuberculosis and an addiction to morphine—and according to legend, having heard that a vengeful Frank James was on his trail—26-year-old Charlie took his own life at Richmond.

A year after Charlie’s death, Bob made his way to Las Vegas, New Mexico, where he and former James Gang member Dick Liddil opened a saloon and dance hall. Some biographical sketches maintain that he also became a town policeman. However, he abruptly left town, purportedly to avoid a gunfight with a desperado.

Further dogging Bob was a popular street ballad of unknown origin that left no doubt as to the composer’s sentiments. The song portrayed Jesse as a bandit cavalier and a hero of the common man:

“Jesse James was a lad who killed many a man

He robbed the Danville train;

He took from the rich, And he gave to the poor.

He’d a hand and a heart and a brain.

“Jesse James was a man, a friend to the poor;

He’d never see a man suffer pain.

And with his brother Frank, he robbed the Chicago Bank,

And held up the Glendale train.”

Conversely, Bob was painted with an entirely different brush:

“It was Robert Ford, that dirty little coward,

I wonder how he does feel,

For he ate of Jesse’s bread, and he slept in Jesse’s bed,

And he laid poor Jesse in his grave.”

And if the stanzas failed to arouse the listener’s ire, there was always the chorus:

“Jesse had a wife to mourn for his life;

Two children, they were brave.

But the dirty little coward who shot Mister Howard**

Has laid poor Jesse in his grave.”

Jesse had lived in St. Joseph under the alias John Davis Howard, a fact that emerged after his death and eventually made its way into the ballad. Oral tradition has it that the song, with all its many damning verses, followed Bob wherever he traveled.

Still rambling the West, Bob opened a saloon in Walsenburg, Colorado, in 1889. Less than a year later, when silver was discovered in the town of Creede, he moved his interests there, but was thrown out of town for shooting out windows and streetlights while drunk. Eventually allowed back in, he built a public house and dance hall named Ford’s Exchange. When fire raged through the business district, destroying his saloon, he erected a large tent to serve as his emporium until a new saloon could be built. This never came to pass.

On June 8, 1892, Bob was standing with his back to the tent door, when a ne’er-do-well named Edward

O’Kelley—for reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained—entered the saloon carrying a sawed-off, double-barreled shotgun. Hearing, “Hello, Bob,” Ford turned around, and O’Kelley emptied both barrels into him. Bob died instantly.

Initially buried in Creede, Robert Newton Ford was later exhumed and shipped back to his hometown of Richmond. His tombstone, which has his birth date wrong by 21 years and ignores his middle name, simply reads,

“Bob Ford

The Man who Shot Jesse James”

Jesse James lies in the Kearney cemetery. Although the current grave marker merely reflects his name and dates, the original stone, in words reportedly framed by his mother, read, “Devoted Husband And Father—Jesse Woodson James—Murdered by a Traitor and Coward whose Name is not Worthy to Appear Here.”

Even in death, it seems, Bob Ford could not escape the public ignominy of his one unforgivable act.

Read more about Missouri’s infamous outlaws here.

After all articles that came from a printed issue put this at the end: Article originally published in the January/February 2024 issue of Missouri Life.