Missouri’s Most Infamous Outlaws

Missouri was once the western frontier and part of the Wild West. In the mid-to-late 1800s, Missouri was known as the Outlaw State, with considerable justification. Missouri contributed far more than its share of bushwhackers, stock thieves, band and train robbers, and killers. Here’s a roll call of some of the most infamous outlaws.

Born from War

One of the standouts was William T. Anderson, who more than earned the epithet, “Bloody Bill.” Before a fusillade of Union bullets ended his career, and Anderson garnered a stunning reputation for savagery. A Kentuckian by birth, he spent his wartime career cutting a swath of mayhem and murder through Missouri. He decorated his horse’s bridle with the scalps of his Yankee victims and established a policy never to spare a captive’s life. However, as bloody-minded, as Bill was, he was outshone for sheer barbarism by his teenage acolyte, Archibald “Little Archie” Clement.

Raised near Kingsville, Little Archie joined Anderson’s guerrillas at the age of 15 and immediately took to partisan life. He stood only five feet tall and weighed 130 pounds, but what he lacked in stature he more than made up for in brutality and sadism. By his 16th birthday, he had earned the epithet “Anderson’s scalper,” for obvious reasons. At one juncture, he left a note on a Union soldier whom he had dispatched that read: “You come to hunt bushwhackers. Now you are skelpt. Clement skelpt you …” As did many bushwhackers, Little Archie continued his depredations after the war ended. Predictably, he died in a hail of bullets, ambushed by an entire militia company on the streets of Lexington, Missouri.

Cut from the same cloth was Missouri native son Sam Hildebrand, the “Big River Bushwhacker.” Sam managed to prolong his career for seven years following the end of the war before being shot dead. Unlike other guerrilla fighters, Sam (who was completely illiterate) dictated his autobiography, which was published in 1870. It sports an impressive if the immodest title, the first part of which reads, Autobiography of Samuel S. Hildebrand, The Renowned Missouri “Bushwhacker” and Unconquerable Rob Roy of America; Being His Complete Confession. Despite its burdensome title, it is a well-illustrated, remarkably lucid, and highly entertaining 300-page tome, detailing the impetus behind Sam’s career as a bushwhacker as well as his actions during the war. Not surprisingly, Sam claimed to have been “driven to it” by war-related outrages committed against him and his family. It was reasoning that was echoed by many Missouri bushwhackers.

Queen of Thieves

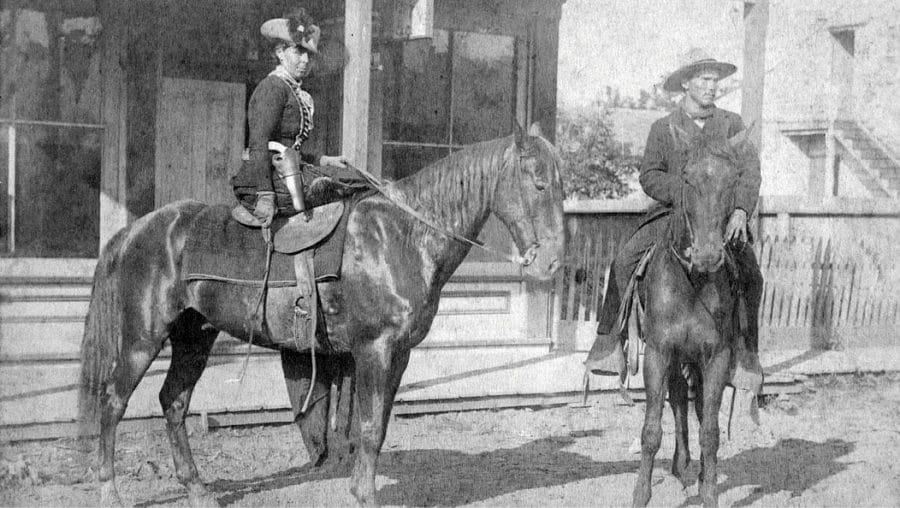

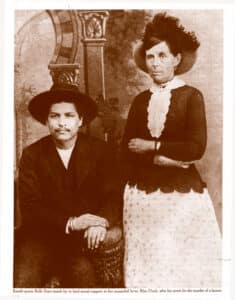

Few Western outlaws have been as inaccurately romanticized as the woman known as Belle Starr. While legend has dubbed her the “Bandit Queen,” Belle was nothing more than a stock thief who served a year in jail for her efforts. Although the glamorous Gene Tierney portrayed her in a 1941 Hollywood biopic, she was far from a dazzling beauty, as her photographs illustrate. Someone who knew her described Belle as “bony and flat-chested with a mean mouth; [a] hatchet-faced, gotch-toothed tart.”

She was born Myra Maybelle Shirley but subsequently tacked on the names of her husbands, Jim Reed and Sam Starr. Belle was raised in Carthage in relative affluence, but the Civil War bankrupted her father. She left home while still a teen and, despite a good classical education, began a lifelong and frequently carnal association with outlaws and other lowlifes.

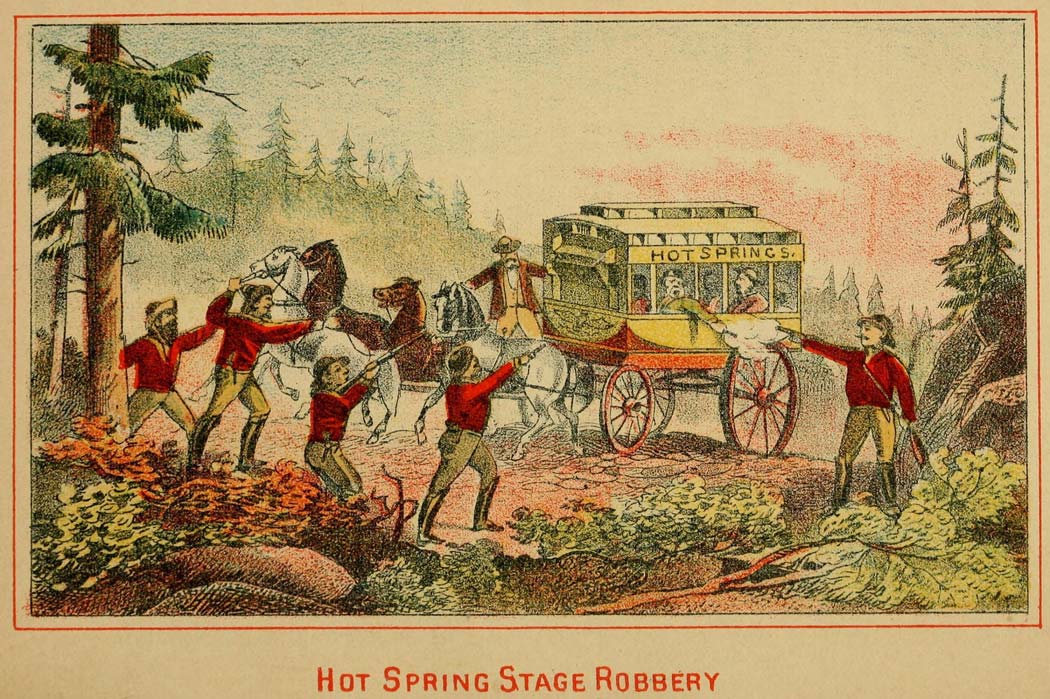

At 18, Belle married Jim Reed, a small-time thief, rustler, and whiskey runner. The marriage lasted for eight years until Reed was shot and killed. After a brief dalliance with stagecoach robber Bluford “Blue” Duck, she took up with Cherokee outlaw Sam Starr, reputedly using her hard-scrabble ranch on the Canadian River as their headquarters. Sam, too, was eventually shot to death, and Belle embarked on a series of relationships with younger men.

On a wintry morning in February 1889, two blasts from a shotgun blew her off her Thoroughbred horse, ending her life but setting in motion a captivating legend. At least three men were suspected of the killing, including Belle’s own son, but her assassin was never identified. Belle was just two days shy of her 41st birthday.

All in the Family

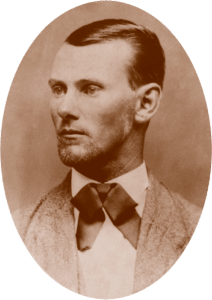

The most notorious lawbreakers to come out of Missouri where the James and Younger brothers. The James boys hailed from Kearney, and the Youngers were raised on a family farm in rural Jackson County. Of the men who made up this quintet of brigands, the name that has irrevocably made its way into the American lexicon is that of Jesse Woodson James.

Physically, Jesse James was unprepossessing. He was of average height and build, and he apparently blinked a lot. He suffered from a lifelong eye affliction, as 1882 biographer J. W. Buel describes: “In his youth, Jesse was troubled with granulated eyelids from which he has never recovered, which is seen in the constant batting of his eyes.” Buel also describes him as “of nervous temperament,” which is not surprising, given his chosen career.

During his lifetime, Jesse was looked upon as America’s Robin Hood, a man driven to the fringe of civilized society, who stole from the banks and railroads that had im- posed themselves on the common man. The legend grew that a benevolent Jesse, as the storied English bandit before him, habitually shared his ill-gotten gains with his less fortunate fellow citizens. In fact, nothing was further from the truth. Remorselessly brutal, he and his associates adhered to history’s first rule of thievery: They stole the money, and they kept it.

During his lifetime, Jesse was looked upon as America’s Robin Hood, a man driven to the fringe of civilized society, who stole from the banks and railroads that had imposed themselves on the common man.

Jesse was fortunate to have an ally in the newspaper business. John Newman Edwards, Confederate veteran, and Lost Cause apologist became the 1870s equivalent of Jesse James’s press agent and elevated a common freebooter to the status of folk hero.

Edwards worked as a newspaper editor until the war broke out, then enlisted in the legendary rebel cavalry General Jo Shelby’s Iron Brigade, and swiftly rose to the rank of major. At war’s end, Edwards rode with Shelby and his die-hards across the border into Mexico.

Of the original gang, only Cole Younger and Frank James would live to see old age. Cole, who claimed to have been shot a total of 20 times during the times he rode with William Clarke Quantrill and Jesse James, reputedly still had 14 bullets in his body when he was buried.

Two years later, the virulently anti-Reconstruction Edwards was back in Missouri, again working in the newspaper business. Shortly after, he co-founded the Kansas City Times, with the express dual purpose of opposing the current military occupation and promoting ex-Confederates for public office. When Jesse James and his minions robbed their first bank, Edwards seized upon them as the perfect vehicle for his propaganda. He painted the Jameses and Youngers—and most especially Jesse—as disaffected Southern ex-soldiers and patriots striking a blow against Yankee oppression.

The relationship was nothing if not symbiotic. For his part, Jesse used Edwards as a vehicle for peddling his own letters to the public. The outlaw was gifted in generating personal propaganda, and Edwards was just the man to put it into print. The two men served each other well.

Never was Jesse in greater need of Edwards’s literary spin than after the James/Younger gang’s 1876 abortive raid on the bank of Northfield, Minnesota. Frustrated when unable to break open the safe, a gang member shot and killed an unarmed teller. As the outlaws attempted to escape, the townspeople shot them to pieces. The debacle led to the wounding and capture of the three Youngers, the deaths of the gang’s accomplices, and a long, desperate flight back to Missouri for Jesse and Frank James.

Northfield effectively ended Jesse James’s outlaw career. Although he planned other raids, nothing transpired. By 1880, John Newman Edwards’s machinations to place ex-rebels in office had paid off, and he had no need for the outlaw. Jesse moved from place to place under an assumed name, finally renting a house in St. Joseph. It was there on April 3, 1882, that gang member Robert Ford, seeking amnesty and a hefty reward, shot the outlaw in the back of the head. Jesse died at the age of 34.

As for the surviving gang members, Cole Younger, who had been shot 11 times at Northfield, recovered to stand trial and, along with his brothers, received a life sentence. Bob, the youngest, died of tuberculosis in prison. Jim and Cole were eventually paroled, and shortly thereafter, Jim took his own life.

Of the original gang, only Cole Younger and Frank James would live to see old age. Cole, who claimed to have been shot a total of 20 times during his rides with William Clarke Quantrill and Jesse James, reputedly still had 14 bullets in his body when he was buried.

Americans love their folk heroes. However, it must be stated that, aside from becoming a popular public figure, there was no glamour in the life of an outlaw. It was a hard, hunted existence in a time when a bandit’s career would likely be cut short by a gunshot or the gallows. Few lived to see middle age, and while a scant handful achieved notoriety, most found only violent death.

To see the full story in our September 2022 issue, pick up the magazine from a newsstand near you or call 1-800-492-2593.

Related Posts

Life on the Run: Riding With the Younger Brothers

In the stories told about them during their careers the Youngers were often cast in the classic Robin Hood mold. It was an image they worked hard to cultivate, but it was only half true. They did steal from the rich but, as biographer T.J. Stiles wrote, “There is no evidence that they did anything with their loot except spend it on themselves.”

7 Outlaw Women From Missouri

From the “Petticoated Terror of the Plains” Belle Starr to the fearless Bonnie Parker of America’s most notorious criminal couple, Missouri holds ties to more than its share of nefarious women.

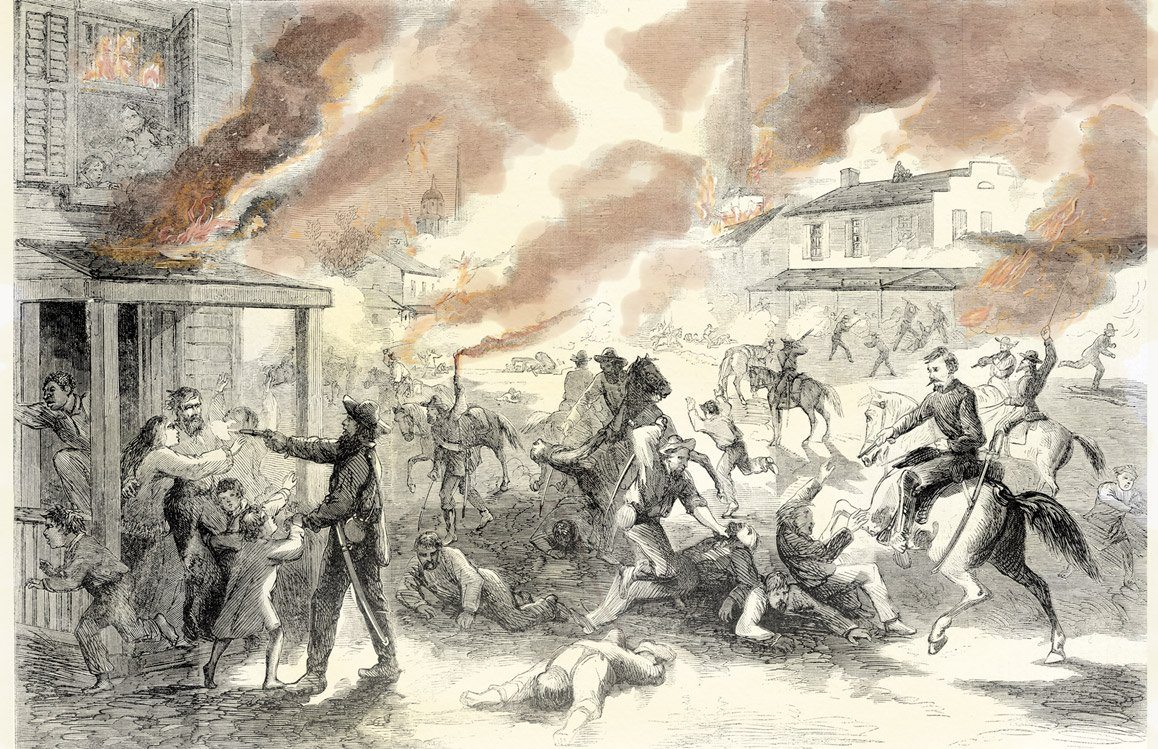

The Man Who Killed Quantrill

The residents of Lawrence, Kansas, would never forget what happened on August 21, 1863, if indeed they were lucky enough to survive. The reason for the bloody raid that left nearly two hundred men dead and caused between $1 million and $1.5 million in damage (in 1863 dollars) is still the subject of speculation.