More than 1,100 Civil War battles were fought in Missouri. Our state parks system focuses on six sites. The Battle of Carthage State Historic Site is one not to be missed. There are interpretive displays and a Civil War museum near the square in Carthage, as well as the fields where the battles took place.

IN A STATE WITH A FAIRLY HIGH PERCENTAGE of families whose ancestors weathered the Civil War in Missouri and whose descendants still live here, the legacy of that conflict is an ever-present aspect of the family lineage. And for newcomers or even visitors, the lingering perception of those times may still fascinate today.

For thousands of Missourians, the most important Civil War site may be the one closest to where they live or where their own ancestors took a stand—and it is likely unmemorialized if it was not a major battlefield.

These sites include skirmishes, guerrilla actions, politically significant places, key garrisons, and important buildings. Nearly twenty years ago, recognizing that it is infeasible and unnecessary for the state to own all these places, park officials embarked on a Civil War marking program, focusing their efforts on sites not already marked by other organizations. Dozens of markers have been erected, and others are planned.

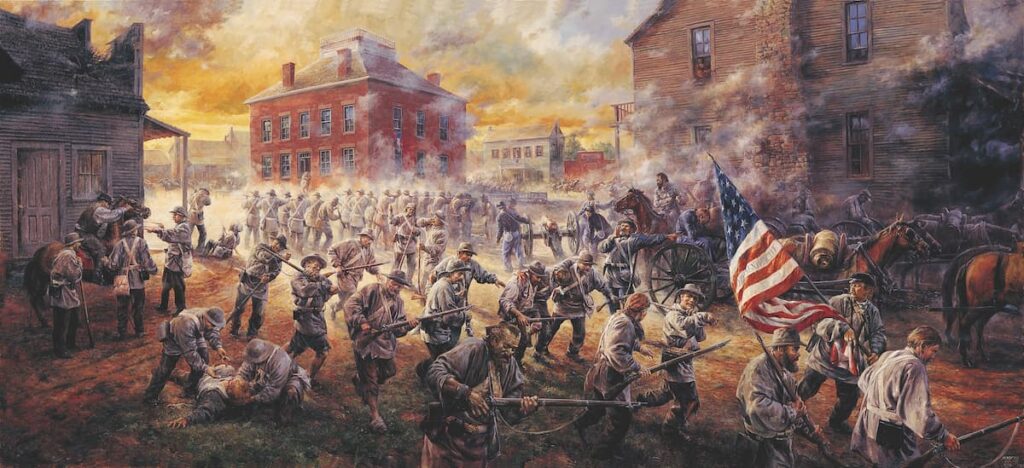

The Battle of Carthage illustrates the problems of preserving and interpreting a site that isn’t a concise, well-bounded battlefield. At Carthage on July 5, 1861, the action was fierce, but it lasted less than a day—never more than an hour or so at any one point—and it swept down nine miles of country road leaving no permanent marks. State park authorities felt it was an ideal candidate for a marker, but local interests wanted more. In 1990, legislation established an eight-acre historic site focused on Carter Spring in the city of Carthage in Jasper County where federal and pro-South state forces ended the day’s hostilities and where both sides bivouacked on different nights.

But the battle was much bigger than the Battle of Carthage State Historic Site and amorphous as well, as is often the case in the chaos of combat. As a result, the presentation is multifaceted. Park officials have placed an interpretive display at the state-owned spring site, but visitors also will want to see a city-owned Civil War museum near the square and take a self-guided auto tour along Civil War Avenue, driving the nine miles north to other scenes of action at Spring River, Buck Branch, and Dry Fork. Dry Fork, in particular, survives almost unaltered, its farm fields and creek probably looking much as they did on the day of the battle.

Photo by Denise H. Vaughn

What actually happened at Carthage on that long July day in 1861 and why was it important? The battle was one in a series of armed conflicts, beginning at Boonville in June and culminating in September at Lexington, where militia forces sympathetic to the South, organized for the most part as the Missouri State Guard, sought to wrest control of the state from federal forces that included among their number some of the hated Yankees from northern states and the “damned Dutch” (regiments made up of German immigrants) from St. Louis, but also a good many ordinary Missourians who remained loyal to the Union.

The battle at Carthage was hardly earth-shattering; it did not produce a clear victory, nor was it particularly well fought. The inexperience of both sides was revealed, and that is not surprising considering how early in the war the battle took place. Bull Run, often referred to as the first battle of the war, did not occur until two weeks after Carthage.

Before the encounter at Carthage, events were going strongly in favor of the Union. Federal troops had driven Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson and his pro-Southern forces from the capital at Jefferson City, routed them at Boonville, and sent them fleeing toward the southwestern corner of the state. Now a Union detachment under Col. Franz Sigel, encamped on July 4 at Carter Spring in Carthage, was trying to prevent Jackson from linking up with other Missouri forces and with a Confederate army under Gen. Ben McCulloch in northwest Arkansas. At Dry Fork Creek about nine miles northwest of Carthage, at eight-thirty in the morning on July 5, Sigel’s and Jackson’s forces met and squared off.

Jackson had about six thousand men, mainly recruits, eager to fight but inexperienced and undisciplined, most armed only with their flintlocks and squirrel rifles and fully a third with no arms at all. Sigel’s force was much smaller, numbering about eleven hundred, most of whom were St. Louis Germans, well armed and well drilled. As the firing began, Sigel, noting an attempt by Jackson’s superior numbers to encircle him and cut off his supply train, commenced an orderly retreat. Thereupon the action shifted southward several miles to the next creek crossing, over Buck Branch, then another three miles to Spring River, and finally into Carthage, where Sigel’s rearguard artillery positioned on the bluffs above Carter Spring continued to cover his withdrawal masterfully.

The battle went down in history as a victory for Governor Jackson’s State Guard. Although his ragtag recruits could not defeat the smaller but better trained and equipped enemy, they had their way on the field and proceeded without further hindrance to their rendezvous with Gen. Sterling Price and the rest of the Southern forces. There they would train, organize, and regroup for the coming advance north.

The Battle of Carthage was an important turning point for the cause of the South in Missouri, even if only for a few months. It raised Southern hopes, and the Missouri State Guard gained a momentum that carried it to Lexington, the high water mark of the Confederacy in Missouri.

And only at Carthage did a sitting governor personally and successfully lead state troops against a US army. Carthage made it clear that Union occupation of Missouri would not be uncontested; resistance would be ferocious and unremitting throughout the long war.

THE CIVIL WAR IN MISSOURI

More Missourians fought in the Civil War, in proportion to the state’s population, than was the case in any other state. Some 60 percent of eligible men saw action—at least 50,000 served the Confederacy and 109,000 the Union. More than 8,000 black Missourians enlisted in Missouri regiments, and others enlisted in other states. About 14,000 Missourians gave their lives for the Union, and even more for the Confederacy.

Over 1,100 battles or skirmishes were fought here, a number exceeded only in Virginia and Tennessee. And the vengeful guerrilla warfare here—described by one historian as the “war of ten thousand nasty incidents”—drew virtually every man, woman, and child into the maelstrom.

Of the literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of sites in Missouri associated with the Civil War, the state park system focuses on six:

- Battle of Carthage, July 1861

- Battle of Athens, August 1861, in far northeast Missouri, possibly the farthest north conflict in the war

- Battle of Lexington, September 1861, which marked the high tide of the Southern cause in the state

- Battle of Island Mound, October 1862, where African American troops for the first time anywhere in the nation experienced Civil War combat

- Battle of Pilot Knob, September 1864, the encounter that doomed Confederate dreams of reclaiming Missouri

- Confederate Memorial, to honor the dead. Many other Missouri parks have Civil War history: Hunter-Dawson, Jefferson Landing, Bollinger Mill, Roaring River, St. Francois, Mark Twain, and Arrow Rock, to name a few. The National Park Service protects the battlefield at Wilson’s Creek as well as Whitehaven, the home of General Ulysses Grant.

Featured image: Left: Both federal and state troops, who were in conflict with each other, bivouacked in this meadow by Carter Spring on successive nights, July 4 and 5, 1861.

Photo credit: Photo by Bonnie Roggensees

BATTLE OF CARTHAGE STATE HISTORIC SITE • CHESTNUT STREET, CARTHAGE

Read about more state historic sites here.

Purchase the Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites book here.

Related Posts

Bollinger Mill State Historic Site

Bollinger Mill and Burfordville Covered Bridge provide you with a step back in time to experience genuine grist milling, a stroll through the oldest covered bridge in Missouri, and a peaceful rest along a tree-lined stream.

Lots of History at the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site

The Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site is a place filled with history. Many battle reenactments have relived the events that took place on Sept., 27, 1864. Visit the fort, bring a picnic, and immerse yourself in Civil War history.

Visit the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site

Lexington, Mo is brimming with annetebellum homes and amazing architecture, and is surrounded by beautiful landscapes. The Anderson House was used as a hospital during the Civil War. The site is most notable for the Battle of the Hemp Bales. Come find out why.