Big Sugar Creek State Parks in the corner of southwest Missouri boasts a cultural history as intriguing as its natural history, but some local legends provoke as many questions as answers. Hike on the Ozark Chinquapin Trail where you can see an array of flora and fauna.

Photo Courtesy of Susan Flader

ENTER INTO A BYGONE OZARK ERA. The uplands are sparsely populated with oaks and hickories. Sunlight trickles down the valleys to meet purple coneflowers amidst green and golden grasses. Dip your hands into a stream alive with spring water seeping from an underground passage, and feel the chill of time immemorial drip from your fingertips. Inhale the rich scent of fallen oak leaves, wildflowers, and mossy limestone. Watch the swooping flight pattern of a resident pileated woodpecker, its wild laugh welcoming you into Big Sugar Creek State Park.

Photo by El Brujo

Like the crystals of a geode within an ordinary rock, Big Sugar Creek is a treasure amid far southwest Missouri’s remote hills. It boasts a diverse array of living communities, such as cherty woodlands and limestone glades that harbor rare, endangered, and regionally restricted plants and animals that flourish in this distinct Ozark landscape. The rugged hills of McDonald County have also given rise to legends, tall tales, and a fascinating history, with considerable uncertainty as to which is which.

There are stories of Pine Wars, with battles fought over rights to valuable pine timber, and a real war, when Northern and Southern armies marched through the county and no one could be safely neutral. The courthouse was burned by bushwhackers in 1863, and in 1939, many scenes in the famous movie Jessie James were filmed nearby because Hollywood executives thought Pineville and the Big Sugar country looked more like 1870s Clay County than Clay County did. There were disputes over land titles and rough justice meted out by “slickers” and vigilantes. A place on the river known as Penitentiary Bend is claimed by some as the site where a sheriff’s posse rounded up a band of outlaws; others maintain as stoutly that miserable prisoners from a Civil War skirmish were once confined there. So this fascinating corner of southwest Missouri boasts a cultural history as intriguing as its natural history, but some local legends provoke as many questions as answers.

The idea for the park dates to the 1970s when naturalists and planners analyzed the park system to identify gaps in its representation of the natural and cultural heritage of the state. The Elk River Hills eco- region in Missouri’s far southwestern corner emerged as such a gap. Years later, in southern McDonald County five miles east of Pineville, some land became available along Big Sugar Creek that was the best

remaining sizable example of the native landscape in the Elk River Hills. Park officials acquired 717 acres in 1991, and subsequent acquisitions brought the total to 2,047 acres by 1994. In 2000, the multiagency Missouri Natural Areas Committee recognized the significance of the park’s remarkable biodiversity by designation of a 1,613-acre portion of the park as the Elk River Breaks Woodland Natural Area. The area includes 345 different species of plants and 134 confirmed species of birds, coupled with the distinctive aquatic fauna of Big Sugar Creek and its tributaries.

Photo Courtesy of Denise H. Vaughn

The park includes two-and-a-half miles of riverfront, a fine setting for river play and exploration, but unlike most rivers in the Missouri Ozarks that drain north, east, and south to the Missouri, Mississippi, and White Rivers, Big Sugar Creek drains southwest into the Elk River and then on to the great Arkansas River drainage, a distinct and powerful landscape. As a result, this beautiful, clear-water, bedrock stream harbors some aquatic species unique to this area of the state, including the redspot chub, bluntface shiner, cardinal shiner, Neosho midget crayfish, and mucket mussel. Big Sugar Creek itself is a compelling resource, but equally significant is the range of steep hills and rocky hollows that cradle the Big Sugar valley and provide habitat for a rich array of species and communities, including the rare Ozark Chinquapin. A variety of interesting and unusual animals also find refuge within the Big Sugar Hills, including the gray bat, Oklahoma salamander, and pine warbler.

In an effort to restore the integrity of dwindling glade and woodland habitats, park naturalists in the mid-1990s began a prescribed-burn program for the park. By reintroducing fire, which was part of the natural cycle in this area, they encouraged some of the original native vegetation. Unfettered by competition for sunlight, the remaining trees flourished, and grasses and wildflowers appeared once again on the hillsides. The results of this burn program are evident along the Ozark Chinquapin Trail, which in part follows a ridge through native grasses under an open canopy of oaks and shortleaf pines.

The park has been only minimally developed over the last two decades. Future plans include a canoe launch and various facilities for visitors, but the bulk of the park, including the natural area, is proposed as the park system’s twelfth wild area. A key feature of the park and wild area is the rugged three-mile Ozark Chinquapin Trail that winds through the Big Sugar hills. The trail gives you a chance to experience this rough terrain as Native Americans and early explorers may have, traversing ancient ridges and valleys through which spring water and rainwater flow in myriad deep hollows to Big Sugar Creek. You might chance upon a whitetail buck along the trail or see a flock of wild turkeys foraging in the woods. Chipmunks scamper through leaves and underbrush to their nests in dead oaks and limestone outcroppings, and armadillos shuffle along, searching for food under the leaves.

Photo Courtesy of Allison Vaughn

This beautiful rugged topography that makes McDonald County such a joy to visit today also somewhat slowed its settlement by pioneers. The uplands, known generally as barrens or flatwoods to the early settlers, were thought to be unfertile and not suited to agriculture, so it was the rich bottomlands along the creeks that attracted the first settlement. On Big Sugar Creek in the vicinity of what would later become the state park, the first land patents were taken out in the 1830s and 1840s. By 1860, there was a low dam across Big Sugar providing water power for a gristmill and later for a sawmill. A small commercial establishment provided store-bought goods for the neighborhood. This little hamlet seems not to have had a formal name until about 1883. In that year of winds and waters, a post office was begun, and even though the village has long since disappeared, this vicinity is still known by that acknowledgment of adverse weather: Cyclone.

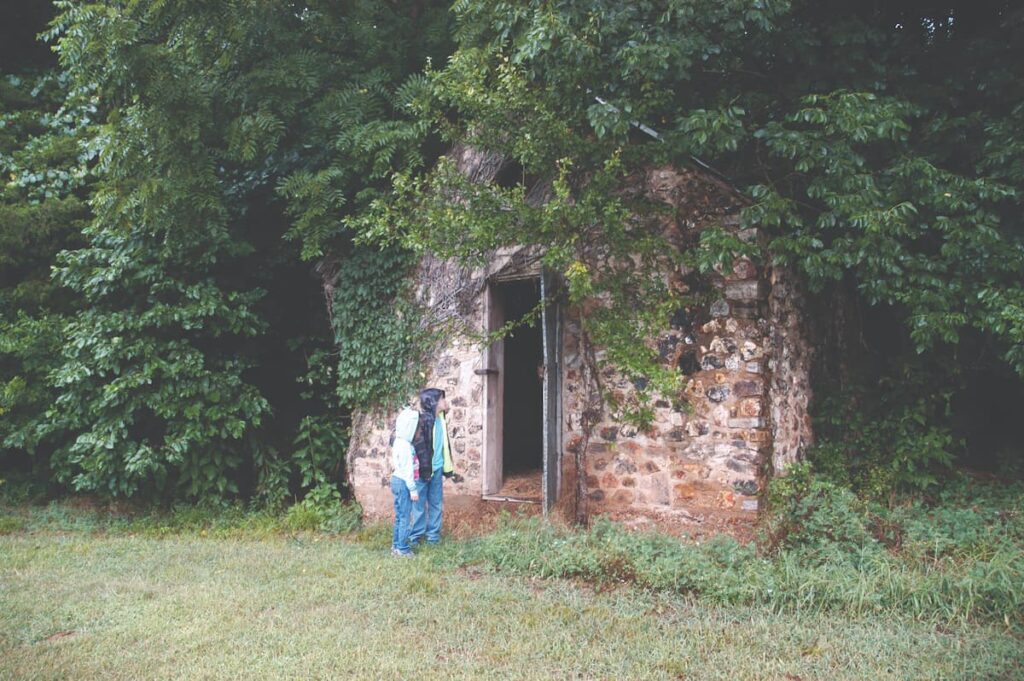

Only a few remnants of these earlier times can still be found in the park. A rock outbuilding that served as a woodshed for Shady Grove School still stands at the Ozark Chinquapin trailhead. About a half-mile along the trail, hikers with a keen eye can discern vestiges of the rock foundation of a house. And across the trail from the house foundation is the concrete foundation of a granary. On the whole, though, nature has reclaimed the man-made structures, and the overall sense of this place is wild and natural.

Photo Courtesy of Steve Bost

Ancient Ozark chinquapins stand in winter like gaunt statues on spare bony ridges, their remnant twisted branches a testament to hardiness. In the draws, chickadees and nuthatches titter as the tinkling streams wind their way to the big creek, where colorful and unusual fish remind us of Missouri’s position as a true crossroads, including links to the great Southwest. Big Sugar is a landscape of rugged beauty and much remaining mystery. It deserves a visit from Missourians curious about the fascinating nooks and crannies of their wonderful state.

THE RARE OZARK CHINQUAPIN SURVIVES HERE

In open, rocky terrain, vestiges of the rare Ozark chinquapin survive as scrubby stump sprouts, which may be viewed from the tree’s namesake hiking trail. Once revered for its tasty nuts, the Ozark chinquapin succumbed to chestnut blight in the 1950s and 1960s, and it continues to be ravaged by this disease, which inhibits survivors from reaching their normal sixty-foot height. In fact, Big Sugar Creek State Park is one of the relatively few places in Missouri in which this species still survives, and it may provide a seed source for efforts underway to reestablish this charismatic plant throughout its former range. Other rare plants found in the park include Ozark corn salad and climbing milkweed.

BIG SUGAR CREEK STATE PARK • BIG SUGAR CREEK ROAD, PINEVILLE

Featured image: In the southwest corner of Missouri, early spring reveals the rugged Elk River Breaks Woodland Natural Area with limestone outcrops, dry cherty slopes, and oaks with scattered shortleaf pine. Photo by Allison Vaughn

Read more about saving the Ozark chinquapin here.

Purchase the Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites book here.

Related Posts

Castlewood State Park

Castlewood State Park has more than thirty miles of hiking and biking trails, eleven of which are open to horseback riders. Experience the feel of a mature floodplain forest with its silver maple, box elder, black willow, white ash, sycamore, slippery elm, and hackberry. Bring a picnic and enjoy the beauty of this park.

Visit the Serene Bryant Creek State Park

Bryant Creek State Park is more than 2,900 acres of pristine forests, rippling waters, and backcountry trails. See trees that may be up to three hundred years old. Set up camp on a gravel bar and do some fishing. Get back to nature at this stunning state park.

Big Sugar Creek State Park is a Treasure!

Big Sugar Creek State Park is full of nooks and crannies that are worth exploring. The rugged landscape is filled with rare plants and animals. This park is one of the only places in Missouri where the Ozark Chinquapin survives.