After one of the more cataclysmic dam failures in American history, Johnson Shut-Ins State Park has been reborn. The pools and rock slides are perfect for the whole family. There is an abundance of flora and fauna as well as hiking trails and the Black River Center.

Photo Courtesy of Susan Flader

THIS PARK IS A PHOENIX, REBORN OF FLOOD and wind rather than fire. Since its inception in the 1950s, Johnson’s Shut-Ins in Reynolds County has been among the best-known state parks in Missouri, but the chutes and potholes of its photogenic shut-ins were ravaged by one of the more cataclysmic dam failures in American history. In the frigid predawn blackness of December 14, 2005, the Taum Sauk Reservoir atop nearby Proffit Mountain suddenly collapsed and in only twelve minutes sent 1.3 billion gallons of water roaring seven thousand feet down the mountainside and into the heart of the park. The rocks, trees, and other debris carried by the water created an immense scour channel and were deposited in the famous shut-ins. Then, just as the cleanup of the park and reconstruction of facilities neared completion, the park’s mountainous wild areas took a direct hit on May 8, 2009, from an extraordinarily powerful windstorm that toppled as much as 90 percent of the oak and pine canopy in some areas. In spite of all this, Johnson’s Shut-Ins is being reborn.

Located in the St. Francois Mountains at the geologic core of the Ozarks, the park is justly famed for its rocks. Pink granites, porphyries, and blue-gray rhyolites offer testimony to an era of primordial volcanism more than a billion years ago. Upstream of the park, the East Fork of the Black River flows through a relatively broad valley, the same valley followed by Route N leading to the park. But as the stream leaves the more easily eroded dolomitic bedrock and meets the resistant igneous rocks of the ancient ash and lava flows, the valley becomes narrow and canyon-like. The water has had to fight ceaselessly, laboriously, for every fracture, every weak joint, straining to find the least resistant course to follow. Sometimes, it has made right-angle changes in direction, creating eddies and crosscurrents. The resulting gorges and rock gardens have come to be called shut-ins. There are other shut-ins in the St. Francois Mountains region, but Johnson’s, named for nineteenth-century homesteaders who actually were the Johnstons, are the most famous.

Photo by Oliver Schuchard

This rugged, nearly impenetrable area was once part of the largest Spanish land grant in Missouri. Sixteen square leagues (nearly 100,000 acres) on the forks of Black River were awarded in 1799 to Father James Maxwell, the Irish Catholic priest of French Ste. Genevieve, who intended to rescue indigent Irish Catholics from British tyranny and establish them here under a benign Spanish monarchy. But Spain transferred the land to France, who sold it to the United States, and the Irish settlement never materialized. There is scant evidence of Euro-American activity in this hardscrabble region until a few homesteaders trickled in decades later. The land was still relatively wild, uncut, and inaccessible when it was first proposed as a state park in 1915.

Much of the original park, including the shut-ins and two miles of river frontage, was assembled over the course of seventeen years and donated to the state in 1955 by Joseph Desloge, a St. Louis civic leader and conservationist from a prominent lead-mining family. The family subsequently donated funds for needed improvements.

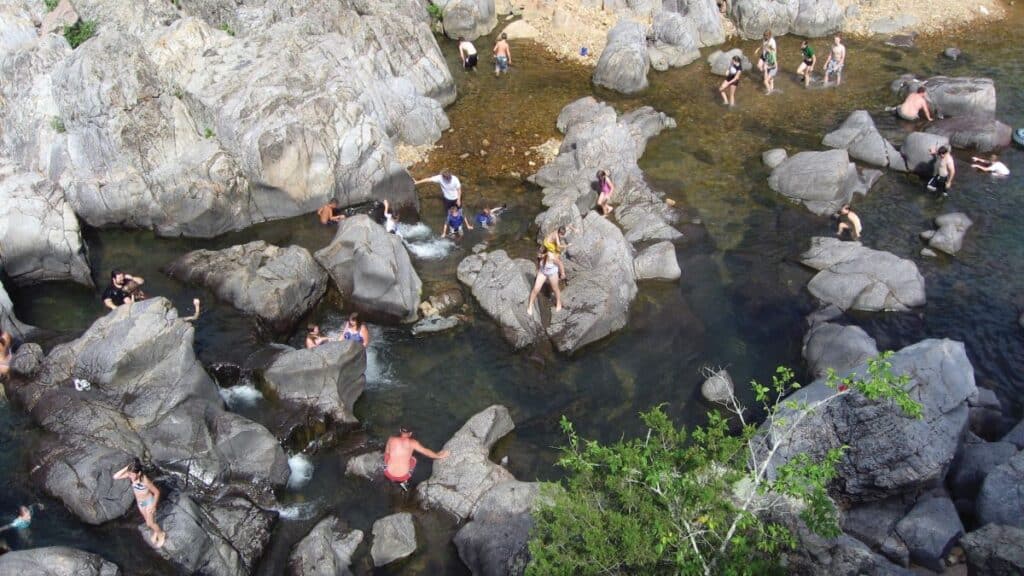

Most visitors to Johnson’s Shut-Ins see only a small part of the park—the visitor center, the picnic grounds, the campground, and the shut-ins overlook. The more adventurous wade, swim, and play in the creek, climbing and sliding on the smooth and slippery volcanic rocks, sitting in the swirling waters of the gravel-scoured potholes—a poor man’s Jacuzzi, especially appealing on a hot summer day.

But the vast majority of the park’s 8,780 acres is a near-wilderness paradise welcoming those hardy enough for vigorous hiking. Nearly three-quarters of this acreage is included in the East Fork and Goggins Mountain Wild Areas. The East Fork Wild Area is generally that part of the park, excluding developments, between Route N and the river. The Goggins Wild Area of nearly 5,000 acres includes the sprawling, four- domed Goggins Mountain northwest of Route N, which was acquired in 1993 through a $1 million gift from the Richard King Mellon Foundation’s American Land Conservation Program. It also includes the southern dome of Bell Mountain and adjoins the 9,000-acre Bell Mountain Wilderness Area of the Mark Twain National Forest.

Photo by Paul Barbercheck

The thirty-three mile Taum Sauk section of the Ozark Trail traverses these wilderness and wild areas and continues east through the huge St. Francois Mountains Natural Area to Taum Sauk and Ketcherside Mountains, making this one of the most significant blocks of wild land east of the Rocky Mountains. Here in these rugged, wooded hills, you can find solitude and wildness—endangered resources in today’s hectic world.

Johnson’s Shut-Ins is a rich botanical reserve with over nine hundred recorded species of trees, shrubs, vines, grasses, wildflowers, and ferns, more species than any other Missouri state park. Why this diversity? This question is best answered by exploring several of the park’s seven trails, which cross a variety of rock types, topographic features, aquatic areas, and elevations. Just below the shut-ins, for example, one can find Ozark witch hazel blossoming in January. One of several different shrubs growing on the gravel washes, Ozark witch hazel has adapted to the frequent rampaging floods by simply yielding its buoyant, rubbery stems to the forceful torrents. This gravel-wash natural community is part of Johnson’s Shut-Ins Natural Area.

A hike into the East Fork Wild Area on the Horseshoe Glade loop trail will take you to igneous rock barrens. On a sunny winter’s day, you’ll pause a moment here to bask in the warmth. On a sunny summer day, you’ll hasten through the barrens back to the shade. Herein lies another key to the park’s botanical diversity. Arid land plants adapted to conserving precious water make their home here. In contrast to these rhyolite rock barrens, the Dolomite Glade Natural Area just off the Ozark Trail is in the southwest corner of the wild area. This is also a hot and open spot, but the soils overlying the sedimentary dolomite rock support several plant species different from those on the igneous rhyolite barrens, including the haunting Missouri evening primrose, which blooms at night.

Photo by Oliver Schuchard

In late winter or early spring, a hike to the East Fork Wild Area may reveal blackened hills, scorched by fire. Park staff perform prescribed burns to mimic the natural fires that once shaped the extensive pine and oak woodlands of this region. Without fire, woody thickets and dense leaf litter would inhibit germination of shortleaf pine and shade out and choke the prairie and woodland wildflowers that grow here.

Upstream in the day-use area is yet another unusual community, an eighteen-acre boggy forest designated as the Johnson’s Shut-Ins Fen Natural Area. Permanently wet soil fed by cool calcareous groundwater is the key to the fen. Here, the coolness simulates the boreal conditions of southern Canada, which were more common in Missouri during glacial times and which nurture plants such as swamp wood betony, bottle gentian, tall sweet William, and blue smooth violet.

Photo by Allison Vaughn

This fen, the campground located nearby, and the entire East Fork Black River through the park, including the shut-ins, were obliterated by the debris-filled torrent that roared down the mountain that wintry morning in 2005. It was one of those rare nights when there were no campground occupants, another miracle, or there would surely have been many lives lost in the raging torrent.

As it was, the orchid-filled forest in Buzzard Rock Hollow on the west face of Proffit Mountain, down which the deluge roared, was scoured clean to bedrock, and a debris dam some twenty feet high blocked the park entrance road and the river nearby. Downstream, more debris and sediment clogged the river, forcing it out of its channel, but it reclaimed an older channel, as rivers will sometimes do. The entire campground was obliterated and strewn with mud and debris, as was the fen nearby. The resistant rhyolite of the shut-ins was still there beneath the murky water, but the shut-ins were now filled with concrete, rubble, plastic, and rebar from the reservoir wall and trees and boulders from the scour channel. The boardwalk along the shut-ins was destroyed, as was virtually all the riparian vegetation. Media coverage was national in scope, and the entire park was closed until further notice.

AmerenUE (now Ameren Missouri), the owner of the reservoir, accepted responsibility for the cleanup and redevelopment of the park, but park staff engaged for years in a protracted tug of war with the engineers hired by the power company to do the job. When sediments kept washing down from the edges of the scour channel, the engineers wanted to stabilize them with fabric and special plantings, but park naturalists insisted on a slower, more natural course. When the river changed channels after the deluge, the engineers wanted to put it back and harden it in place with concrete, but park managers argued instead for gently encouraging it to seek its own meandering course through its new floodplain. When test excavations of the deeply buried Johnson’s Shut-Ins Fen Natural Area suggested that the original plants were still in place under many feet of sediment, park naturalists guided crews with excavation equipment and dump trucks and then with shovels and hand trowels in the painstaking removal of the debris and sediment to uncover the fen plants and give them another chance at life. Some of the fen’s characteristic plants survived, but it remains to be seen whether the fen will resume its natural hydrologic functioning. On downstream in the shut-ins themselves, an extraordinary amount of debris was removed, some of it with helicopters, to avoid further disturbing the area and to make it safe once again for swimmers.

Photo by Allison Vaughn

Meanwhile, park facilities were completely redesigned and rebuilt. The old campground along East Fork Black River was abandoned, and a new one was installed a mile north on the Goggins tract well out of the floodplain, complete with new camper cabins, an equestrian area, and links to a ten-mile equestrian and hiking loop trail on the east slope of Goggins Mountain. The day-use area along the creek was enlarged, though it will take decades for the shade trees to grow, and the boardwalk along the shut-ins was rebuilt. There is a new Black River Center with exhibits about the park, the St. Francois Mountains, and the reservoir collapse. A new trail with an interpretive pavilion and overlook provide access to the scour channel, and there are exhibits along Black River and elsewhere in the park as well. All of this new development inevitably has a raw and unshaded aspect, but nature will gradually soften and beautify the park.

Ameren has rebuilt its Taum Sauk Reservoir, and the plant is once again producing electricity. Its high white walls and lights are much more intrusive on the natural scene than the old reservoir, but Ameren insurance picked up the astounding $130 million tab for the cleanup and the reconstruction of park facilities. A complete natural recovery, though underway, will require generations or possibly centuries.

A year before the 2010 dedication of the new park facilities, the park was struck again, but this time with the massive storm of May 8, 2009, which included gale-force, straight-line winds with some forty com- panion tornadoes extending more than a thousand miles from Kansas across the Ozark Highland to eastern Kentucky and Tennessee. It was of a magnitude so far beyond that of any similar event ever before recorded by the National Weather Service that experts called it a super derecho. Well over 100,000 acres were severely impacted in the southeastern Ozarks, including more than a thousand acres in the East Fork Wild Area, on Goggins, and in neighboring Taum Sauk State Park. Elsewhere in the Ozarks, logging crews scrambled for years to salvage downed timber. In the state park, it took park crews and volunteers years to reopen the more remote trails. The oak and pine canopy was damaged over a broad acreage, but prairie forbs and grasses not documented in the original floral survey in 1977 flourished under the newly opened canopy. Within two years, breeding birds showed greater abundance and diversity than in nearby areas not impacted by the wind. There was also new reproduction of shortleaf pine that historically characterized this area. The extraordinary response of vegetation after the great windstorm has encouraged staff to extend prescribed burns to additional areas to facilitate natural recovery of the native oak and shortleaf pine woodlands.

Johnson’s Shut-Ins had been loved nearly to death by the 1970s. It was closed for a time in the 1980s and redesigned as a controlled-access park limited to one hundred cars at a time to ensure a better experience and reduce impact. When the park was again closed for several years after the deluge, the traffic pattern was redesigned to accommodate more vehicles for camping and day-use in other areas, but the parking lot for the shut-ins is still limited to just one hundred cars.

Photo by Jim Rathert

If you should find a line for the shut-Ins when you arrive, especially in summer, there are other places to park to walk the trails and also other beautiful parks in the vicinity. Johnson’s Shut-Ins is being reborn in the wake of disaster, and the process is as fascinating as it is complex. Come and experience the healing and the joys of this fabulous park.

ONE-THIRD OF OUR NATIVE FLORA

Johnson’s Shut-Ins is home to more than nine hundred plant species, almost one-third of Missouri’s entire native flora. Twenty terrestrial natural communities occur here, which is nearly a quarter of those that have been identified anywhere in the state. Here are the twenty terrestrial communities:

- Dry-mesic Chert Forest

- Dry-mesic Igneous Forest

- Riverfront Forest

- Dry Limestone-Dolomite Woodland

- Dry Chert Woodland

- Dry-mesic Chert Woodland

- Dry Igneous Woodland

- Dry-mesic Igneous Woodland

- Dry-mesic Bottomland Woodland

- Dolomite Glade

- Igneous Glade

- Dry Limestone-Dolomite Cliff

- Moist Limestone-Dolomite Cliff

- Dry Igneous Cliff

- Moist Igneous Cliff

- Igneous Talus

- Gravel Wash

- Stream Bank

- Ozark Fen

- Forested Fen

List by Paul W. Nelson, based on The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri (2010 edition), by Paul W. Nelson

Featured image: The December 2005 collapse of the Taum Sauk Reservoir sent 1.3 billion gallons of water and debris roaring down Proffit Mountain into Johnson’s Shut-Ins State Park, scouring a path down the forested mountainside to bedrock and obliterating the park superintendent’s home and the campground in the valley.

Photo by Scott Myers

JOHNSON SHUT-INS STATE PARK • 148 TAUM SAUK TRAIL, MIDDLE BROOK

Order Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites book here.

Read about a scenic drive you can take to enjoy Johnson Shut-Ins and other sites here.

Related Posts

Castlewood State Park

Castlewood State Park has more than thirty miles of hiking and biking trails, eleven of which are open to horseback riders. Experience the feel of a mature floodplain forest with its silver maple, box elder, black willow, white ash, sycamore, slippery elm, and hackberry. Bring a picnic and enjoy the beauty of this park.

Get Out and See Big Oak State Park

You have got to see these trees. Big Oak Tree State Park is home to one national champion, a pumpkin ash, and three state champion trees, overcup oak, sweetgum, and persimmon. The ancient cypress are awe inspiring. The park is also a bird watchers dream with more than 150 known species chirping from the trees.

Hiking Graham Cave State Park

Head over to Graham Cave State Park to walk in the footsteps of early Missourians.