Lake of the Ozarks State Park has an interesting history. Learn how the lake itself came to be. More than just a lake for boating and fishing, the park is filled with trails, caves, miles of shoreline, great fishing, camps, an airport, and so much more.

Photo by Oliver Schuchard

MISSOURI’S LARGEST AND MOST VARIED state park is an inheritance from the Great Depression. The farm economy was collapsing even before the historic stock market crash in 1929, the event often cited as triggering the economic decline that prostrated not only America but most of the industrialized world. Swept into the presidency by an unhappy electorate in 1932, the pragmatic and innovative Franklin D. Roosevelt quickly launched a series of programs aimed at relieving unemployment and widespread human distress.

Some of these New Deal programs were designed to relieve problems in rural America. Crop and livestock prices had collapsed, and small-town banks were going broke. Mortgage foreclosures had turned thousands of once landowning farmers, the descendants of proud homesteaders, into impoverished renters or unemployed wanderers. Roosevelt and his advisers were sensitive to problems of both farmers and land misuse. One of their programs was to buy tracts of land in areas where the terrain and the soil—steep, rocky, and thin—made them submarginal for agriculture. The farmers would move to better lands or into different occupations, and the acquired lands were turned into primitive parks or public recreation areas.

Photo by Oliver Schuchard

As part of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, a system of Recreational Demonstration Areas (RDAs) was authorized to test the feasibility of converting submarginal farmlands near large population centers into outdoor recreation areas suitable for transfer later to the states or other units of government. By 1939 there were forty-six such areas in twenty-four states, including three in Missouri, all managed by the National Park Service. Beginning in 1942, they were conveyed to the states; the ones in Missouri were transferred in 1946.

In addition to this RDA, assembled in 1934 around the Grand Glaize Arm of the Lake of the Ozarks, the others were Cuivre River State Park in Lincoln County and Knob Noster State Park in Johnson County. While this area wasn’t as close to either St. Louis or Kansas City as the other two, one special feature surely attracted the New Deal planners to this region in hilly Miller and Camden counties as they were thinking about recreation: the lake itself. It was formed in 1931 as the Union Electric Company of St. Louis completed construction of Bagnell Dam on the Osage River, the largest hydroelectric impoundment in the Midwest.

The new dam backed water up the meandering main stem of the Osage and its many tributaries that descended through precipitous little valleys, creating a reservoir of 55,342 surface acres with some 1,150 miles of shoreline. Grand Glaize Creek was one of the more scenic tributaries, and it had already been identifi ed as a potential park site by planners working for Union Electric. Fifteen linear miles of the creek and eighty-five miles of shoreline were to be encompassed with- in the federal recreation area. Thus it could have charming lake vistas, swimming beaches, facilities for boating and fishing as well as camping and picnicking, and miles of trails for nature lovers and seekers of solitude. Lake of the Ozarks State Park has all of these within its 17,600 acres—making it far and away the largest park in the system.

In the 1920s, Union Electric, empowered with a license from the Federal Power Commission, had gone about aggressively buying all the land needed for its new reservoir. It acquired most of it in fee, some by condemnation, but took only “flowage easements” in some cases where only a small part of a farm would be inundated at the lake’s highest level. Thus, while the federal agencies were purchasing other lands in the planned recreation area, they also negotiated with Union Electric for its previously acquired lands in the Grand Glaize area. The company’s land records show that the transfers to the federal government took place from 1935 to 1937, mostly at a nominal price since this was at the depth of the Depression and submarginal farmland wasn’t worth much for any purpose. At any rate, Union Electric was required by federal regulations to divest itself of lands not actually needed for operation of its hydro-electric project. Future fortunes were to be made in resort, commercial, and residential development around the lakeshores, but not by Union Electric.

Photo Courtesy of Missouri State Parks

Although the utility company could condemn land, and did, the federal agencies chose not to exercise the power of eminent domain for RDAs. Despite the economic straits of the era, a few landowners chose to hang on to their property. There remain today a number of private parcels within the park boundaries.

Group camps constructed in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) are a distinction and attraction shared with the other two former federal RDAs and several other parks. Perhaps because it is the largest, Lake of the Ozarks has the most: Camps Red Bud, Pin Oak, Clover Point, Rising Sun, and Hawthorne. Another, Pe-He-T’se, has now been dismantled, and Hawthorne has been closed. Hawthorne was used from 1982 to 2005 to house low-security prisoners employed for maintenance tasks in the park through an arrangement with the state Department of Corrections. The camps are frequently reserved in warm weather months by Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, Future Farmers, and 4-H clubs but are available for rental by other youth and adult organizations. Red Bud, the smallest, can accommodate groups as small as twenty or as large as forty-four. Rising Sun can take as many as two hundred. Clover Point, often used by adult groups such as the Audubon Society of Missouri, was renovated in the early 1980s by the Young Adult Conservation Corps, a federal program reminiscent of the CCC.

Pin Oak, long known as the Girl Scout Camp, features primitive cabins in the woods, tastefully spaced along the shoreline so the young campers could go to sleep listening to the night music—owls, whippoorwills, and the lapping lake waters—rather than voices in a neighboring cabin. It was restored to its original CCC integrity in 1989 but with modernized dining and bathing facilities. The State Park Youth Corps, another program reminiscent of the CCC, was working on cabins at Pin Oak and in other group camps in the park in 2010 when the Pin Oak dining lodge, considered one of the finest examples of CCC architecture in the park system, was struck by lightning and burned to the ground the night of September 3. Gov. Jay Nixon pledged to rebuild, despite the most severe financial trauma since the Great Depression. By 2013, the lodge was rebuilt on the original footprint, as close in style and materials to the original lodge as possible but with modern improvements. This was accomplished by a remarkable partnership—also reminiscent of the CCC—between Missouri State Parks, State Fair Community College, and the Missouri Department of Economic Development, which provided a $1.5 million federal block grant. The college’s construction technology students traded their labor for college credit and construction experience.

The park is a treasure trove for social and architectural historians of the twentieth century; in fact, some old log buildings that were salvaged by the CCC date from the nineteenth century. Other new ones were carefully crafted to match closely the older structures. The park and its main road, Route 134, have been designated a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of the prime examples of CCC-era, hewn-log construction, the beautiful rustic bridges, and the extensive network of CCC-built stone ditch-dams that provide erosion control and add to the charm of the beautifully designed road. All of Camp Pin Oak and the central area of Camp Hawthorne are separate historic districts on the National Register. Many other CCC-built structures in the park—such as the park office, the log trail center, and features associated with Public Beach No. 1—also appear on the register.

As a water-based park, Lake of the Ozarks offers excellent opportunities for swimming and boating. Grand Glaize Beach and Public Beach No. 1 are longtime favorites of park users. The park offers a popular full service, concession-operated marina at Grand Glaize Beach, which also includes one of the larger boat ramps on the lake and provides access to miles of undeveloped shoreline favored by fishermen. A smaller marina at Public Beach No. 1 and other boat launch areas are used by campers and day users. Public access is an important factor, given that most of the lake’s shoreline is privately owned.

Away from the waters of the reservoir, the landscape is largely the dry upland chert woodlands common in this part of the Missouri Ozarks. Oak species predominate, but in April when the oaks are just budding, an understory of flowering dogwood and serviceberry blossom into breathtaking beauty. A visitor who takes the trails finds fascinating natural diversity in numerous small glades (more than twenty have been counted in the park), sundry calcareous wet meadows and fens, dolomite bluffs reaching down to the lake, and marshes, spring-fed or in the shallow fringes of the impounded water. Historically, the park would have had open woodlands with widely spaced trees and an understory of prairie grasses, and a few such areas have been restored by park staff with prescribed fire. Each terrain supports its characteristic community of wildflowers, grasses, or sedges and other plant life. The fauna, naturally, is also diverse. Aside from offering glimpses of white-tailed deer or the stealthy wild turkey, this park is noteworthy among birders for migrating hawks in the fall. In winter, bald eagles are easily seen soaring over the secluded coves. And, standing three feet high, the great blue heron accents primordial misty lake shores early in the morning.

Photo by Scott Myers

Befitting the largest park in the system, there are twelve trails totaling more than forty miles, several providing access for bicyclists, equestrians, and wheelchairs, and for good measure in a water-based park, a ten-mile aquatic trail running the length of Grand Glaize Arm and marked with buoys keyed to a guide. The longest trails, about thir- teen miles each, are the Trail of Four Winds in the northeast part of the park, open for biking and horse riding as well as hiking, and the Honey Run Trail in the southwest, suitable for mountain biking as well as hiking. The latter traverses not only hilly post oak woodlands and bottomland communities along Honey Run Creek but also an unusual type of ridge-top wetland community called upland flatwoods, in which the frajipan soil structure causes water to pool on the surface during the rainy season but crack when it becomes dry, favoring plants adapted to both wet and dry conditions. The three-mile Woodland Trail loops through a portion of the 1,275-acre Patterson Hollow Wild Area, while across the road from the trail center the short Bluestem Knoll Trail meanders through woodlands and glades that have been carefully restored with prescribed fire. Other short trails follow the lakeshore and traverse uplands in the vicinity of campgrounds, cabins, beaches, and picnic areas.

Photo by Cindy Hall

In the eastern end of the park is an unusual, possibly inappropriate, feature for a state park, the Lee C. Fine Memorial Airport. The airport is operated in partnership with the city of Osage Beach and serves the resort area around the lake. Named in honor of a popular official who died suddenly in 1966 in his second year as director of state parks, it is a reminder of the days of grandiose planning in the 1960s when federal dollars flowed freely for regional economic development. Officials envisioned a $5 million convention center and luxury resort at which the governor could host his colleagues at the national governors’ conference. The jetport that was to trigger an “economic explosion” in the lake region was built, but legislators turned thumbs down on the convention center. The state proved unable to attract private investors to build a resort on park land.

Photo by Susan Flader

Even so, the lake area is one of the most intensively developed playgrounds in the United States, with many lake roads lined with lodges, restaurants, tackle and curio shops, and a variety of rides, water slides, and other places of entertainment. Indeed, what was once an area catering seasonally to the fishing, boating, swimming, and sunning crowd has now become urbanized with extensive shopping centers and a growing year-round residential population.

Photo by Cindy Hall

Thus, it is all the more remarkable that just a short turnoff from the Highway 54 Expressway, one finds the state park, a 17,600-acre oasis of natural beauty and tranquility where there are no corny signs, no gar- ish neon or billboards, and no angry honking of horns. It is the public’s great good fortune that the Grand Glaize shores and surrounding lands were kept in the public domain and in their natural state.

Photo by Scott Myers

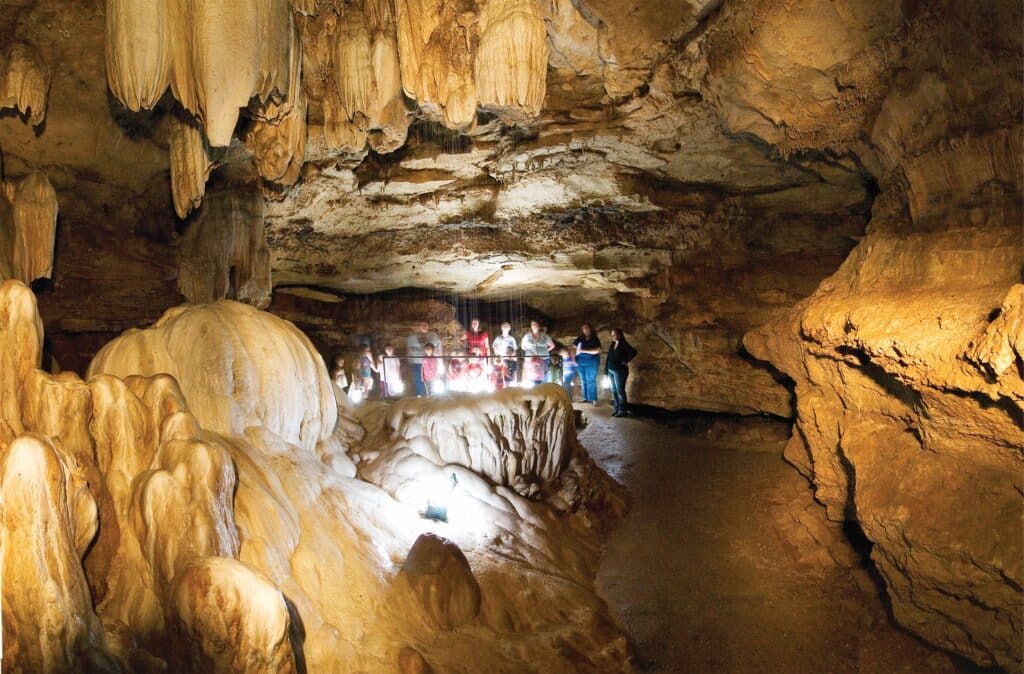

The Lake of the Ozarks State Park was augmented in 1978 by the acquisition of Ozark Caverns, a major Missouri cave that had been commercially operated from 1951 until its transfer. With the cave came 350 acres on the southern edge of the park. It is one of three show caves in the state park system, in addition to Onondaga and Fisher Cave in Meramec State Park. All were once privately owned and operated commercially for the tourist trade.

Ozark Caverns was never as splashily illuminated or as much modified inside as some show caves, and park managers have removed the electrical wiring. Here, visitors carry lanterns and view the speleological wonders as the first explorers did, with candles or miner’s lamps.

Seeps from the sides and ceiling dissolving and redepositing carbonate materials have created a typical cave wilderness of stalactites, stalagmites, “soda-straws,” helectites, and cave corals. The most famous formation is Angel’s Shower. In this speleothem complex, a massive group of stalactites “rains” a continuous shower that falls free for eight feet to be caught in a shining (when lighted) crystalline basin rising from the floor of the cavern. Built up over who knows how many thousands of years, Angel’s Shower is highly unusual, a type of formation found in few other places in the cave world.

The guided tour traverses about a half-mile, round-trip. En route, you might see a sleeping bat, usually the tri-colored bat, a solitary species clinging to the ceiling, or perhaps a little brown bat or a big brown bat. Rare gray bats, mostly male, often inhabit an unvisited part of the cave. The visitor may also glimpse the blind grotto salamander in the cave stream. A few small invertebrates live in the darkness, and what appear to be claw marks in soft clay suggest that bears once visited.

Ozark Caverns was originally known as Coakley Cave, named for an Irishman who settled in the little valley, still called Coakley Hollow, shortly after the Civil War. The cave was known before that, as names inscribed on a “name wall” date back to the 1850s. Coakley installed and operated a gristmill until about 1890, when he moved the mill and machinery to a site near the thriving town of Linn Creek—now submerged beneath the Lake of the Ozarks. Remnants of a milldam can still be seen just downstream from the confluence of the cave stream with the larger spring-fed Coakley Hollow Creek, an Outstanding State Resource Water.

Boggy open meadows, or fens, dot the creek. Fed by cold, seepy groundwater, they resemble boggy wetlands found to the north in Minnesota or Canada. Rare plants like Riddell’s goldenrod, swamp wood betony, and various sedges are relics perhaps left behind thousands of years ago when glaciers retreated from northern Missouri. Where once an old house stood in front of the cave entrance, today there lies a lush fen restored by removing the fill gravel placed there decades ago. So unique is this spring-fed valley that the stream and its fens have been designated Coakley Hollow Fen Natural Area. A loop trail explores the hollow and the nearby uplands, home to an area of upland flatwoods that has also been a focus of restoration for more than a quarter century. An inviting visitor center with a museum, situated fifty yards from the cave entrance, orients visitors to the forces that created not only the cave but also the entire park.

LAKE OZARK STATE PARK • 403 MISSOURI 134, KAISER

To order a copy of the Missouri State Parksand Historics Sites book click here.

Read more about other state parks here.

Related Posts

Missouri State Library Established

On January 22, 1829, the Missouri State Library was established in Jefferson City.