The historic route took early automobiles through the Show-Me State

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Missouri Life magazine.

From my backyard in Cameron, I can watch cars driving up and down a stretch of highway. A century ago, our property was a pasture from where grazing cattle could have seen farm trucks going to market and early automobiles traversing a north–south route less than a mile away. The cows couldn’t have known it, but they were witnessing history being made. These days, the street that Cameron residents know as Chestnut runs parallel to Highway 69, but back then, Chestnut was part of a grand transportation endeavor known as the Jefferson Highway.

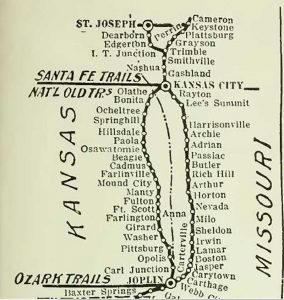

I had recently read The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles, and I began to wonder about this once famed and likewise presidentially named route that ran so near my house. A 2,300-mile linking of paved roads running through longitudinally aligned towns, the Jefferson Highway originated in the evergreens of the Canadian province of Manitoba and meandered southerly to the tropical palmettos at its terminus in the state of Louisiana.

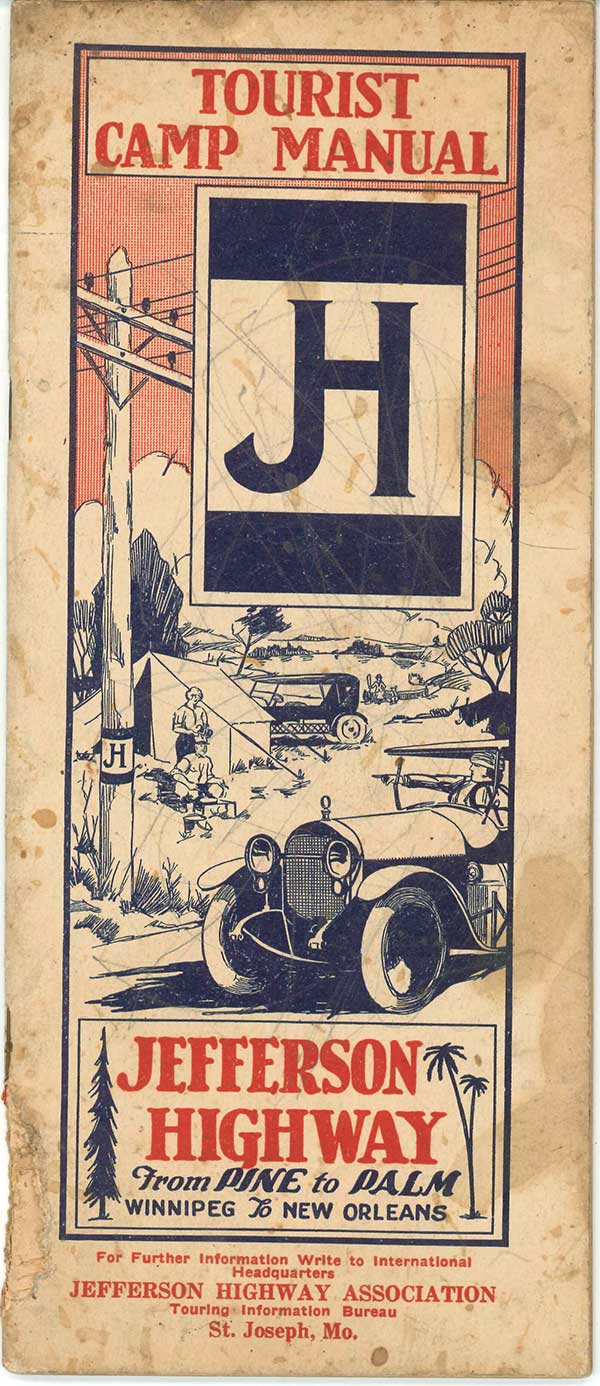

With its motto “From Pine to Palm,” and named for the man responsible for the Louisiana Purchase, the eponymous highway roughly paralleled what would have been the Purchase’s easternmost boundary. Magazine publishing magnate Edwin T. Meredith devised this transportation scheme in 1915 to connect hard-surface routes for farmers traveling to market.

Smack dab in the middle of the country, the Jefferson Highway intersected with another famed historic autoroute: the Pikes Peak Ocean to Ocean Highway. A depot-turned-history museum now sits near the junction of the two roads in Cameron, a former rail town reputed to be at the crossroads of the nation.

Stan Hendrix, a volunteer researcher with the Cameron Historical Society and Depot Museum and the area’s foremost authority on the route, speaks with pride about the town’s role in highway history.

“There were almost no state or federal funds for building highways in 1915,” Stan says. “Railroads got all the money and consideration, so if a town or county wanted the highway to bring commerce, it had to fund it themselves.

This was a massive project for every town along the way. Everyone gave money and pitched in on dragging the roads and making sure the roads were safe to allow the traffic. Communities would work weekends. The churches gathered to provide meals for all the local men who donated their time and equipment to building this new idea called a highway.”

According to Stan, more than 90 percent of the original route is still in use today, albeit under different names. Beginning when it was founded in 1915, the Jefferson Highway Association (JHA) put out a monthly magazine called The Jefferson Highway Declaration chronicling the highway’s origin and promoting its development and expansion. Jefferson Highway enthusiasts still publish the journal. There is also a Jefferson Highway Facebook page and an annual conference to preserve the route’s link to the past.

The JHA allowed municipalities to use its signs, which featured an interlocked, blue J and H. An abandoned bridge at a roadside park near Albany in Gentry Country still bears the distinctive blue and white emblem of the Jefferson Highway.

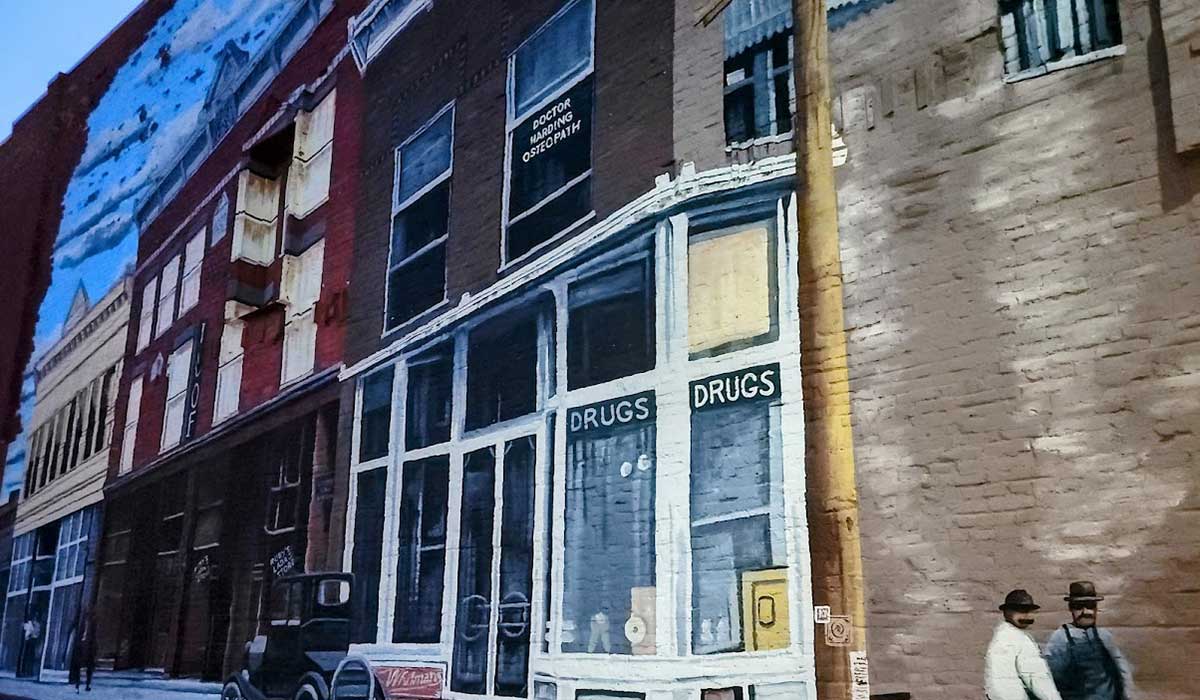

The Jefferson Highway gave its name to more than just a road. A hundred years ago, The Jefferson Highway Cafe on the northwest corner of Third and Walnut in Cameron began serving locals and travelers. Ben Sullivan, the original proprietor, advertised a “Dining room for folks who wish it. Day and Night Service.” Sullivan’s establishment boasted that it had a steam-heated table that kept food warm, and it offered “cantaloupe and watermelon on ice.”

In 1939, in a literal 90-degree turn of events, the Jefferson Highway Cafe’s new owners changed its name to the Ocean to Ocean Cafe to reflect its location along the east-to-west highway. The historic spot is still making people smile, but now as an orthodontist’s office. Stan explains how the highway system went from a citizen-led effort to a government enterprise.

“The government was hard to get on board until World War II, when they realized moving military equipment and troops by rail alone was limiting,” he adds. “They started considering highways and eventually decided it was time to number them and get behind the movement.”

By the mid-20th century, state and federal agencies had designated roadways with a numbering system, including another stretch of the Jefferson Highway renamed Route 66. Counties adopted letters, making the Jefferson Highway the road not taken, at least not by that name.

Related Posts

Web Extras: Tom Sawyer and Jefferson Highway

The 1973 film adaptation of Tom Sawyer, filmed entirely on location in Missouri, featured some very grand female stars, including one that was uncredited yet central to the story.

Jefferson City is the capital of antique shopping!

Whether you are an avid antique collector or prefer to casually peruse, antique and vintage shopping in Jefferson City (JCMO) is a delightful experience for all involved. From curated décor to the quintessential comic book, the Capital City has you covered.

Come explore and discover Jefferson City!

Along with its historic portfolio, Jefferson City, Missouri has much to explore in the rolling hills that surround the incredible Missouri River. For those feeling a strenuous bike ride or a casual stroll, JCMO has activities for every level of outdoor enthusiast.