Known for such compositions as “The Entertainer” and “Maple Leaf Rag,” Scott Joplin is one of the most important figures in ragtime music. At the Scott Joplin House State Historic Site, visitors can retrace his time spent in St. Louis.

Photo courtesy of Peter Ciro

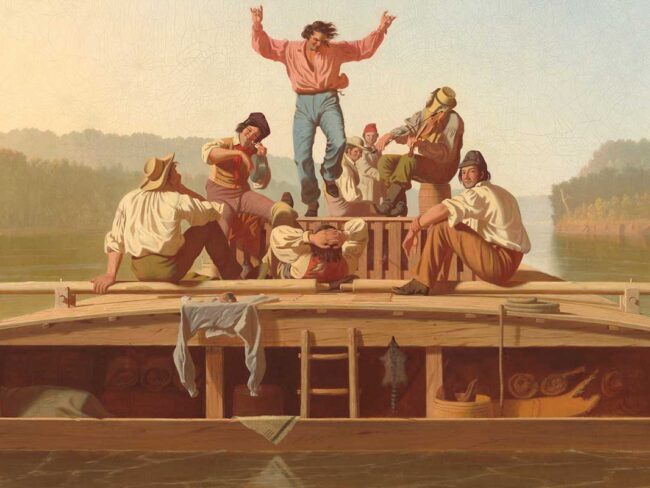

Scott Joplin was the king of Ragtime, and John S. Stark proclaimed him so. Between them, a composer and his publisher, they had a major hand in the direction and sound of American music in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Scott Joplin was born around 1867 to Jiles and Florence Joplin, a musical family in northeast Texas. He grew up in Texarkana and exhibited musical talent at an early age. He learned to play several musical instruments: the banjo, bugle, cornet, violin, and eventually the piano. As a youngster, Joplin studied with a local Texarkana music teacher, Julius Weiss, who recognized his talent and provided free instruction.

Almost no factual information has survived concerning his teen and young adult years. Some musicologists speculate that Joplin took up the life of an itinerant musician, playing piano in bars and honky-tonks in red-light districts in towns along the rail lines, which was an avenue of employment for Black musicians in those days. By 1891 he was performing with a Texarkana minstrel group, and in 1893, he toured with the Texas Medley Quartette, a Black vocal group.

Photo courtesy of the Missouri Division of Tourism

In 1894 he was living in Sedalia, Missouri, where he played cornet in the Queen City Cornet Band, led his own six-piece dance band, and still occasionally toured with the Texas Medley vocal group. But he made his mark by playing piano at the 400 Club and Maple Leaf Club, two Black social clubs in town where he continued to hone his skills in the free-flowing, improvisational, artistic expression of Black musicians from the minstrel tradition. He also attended the George R. Smith College for Negroes, learning the formal structure of classical music and accurate musical notation, so that he could record on paper the African American rhythms he had learned. Joplin eventually became the leader in a new, syncopated musical genre that was becoming a national sensation—ragtime.

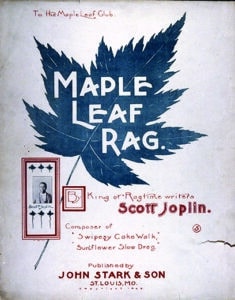

Joplin’s composition, the “Maple Leaf Rag,” became immensely popular and boosted both Joplin and his publisher’s prospects. John S. Stark had been an ice cream maker and a piano and organ salesman, and he had taken over a failing music-publishing house in Sedalia. Riding on the success of “Maple Leaf,” Stark relocated the publishing company to St. Louis and Scott Joplin soon followed.

Musical genius or not, as a Black man Joplin had limited options for housing in turn-of-the-century St. Louis. The building he and his new bride, Belle, moved into at 2658A Morgan, now Delmar Boulevard, had in the mid-1800s been part of a prosperous German neighborhood, but by 1900, most German families had moved to neighborhoods farther west. The house had been built as a duplex but later was converted into a four flat as rental property by enclosing the staircases in each side of the duplex with board partitions so that the second floors could be rented as separate apartments or even single rooms. This area had become the most densely populated part of the city. Older residences had become flats, and new multifamily tenements constructed in the backyards of the older homes now lined the alleys cheek by jowl. Joplin had moved into a busy, bustling neighborhood of the working poor: waiters, janitors, porters, firemen, laborers, and, yes, musicians. A few of the original German families were still there, along with the most recent poor white immigrants to the city, but the district had become increasingly Black.

Photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks

This was the beginning of a productive time for Joplin. He began to perform less and became more of a teacher and composer, although he occasionally performed at Tom Turpin’s Rosebud Café. Advertised as the “headquarters for Colored Professionals,” the Rosebud was the epicenter of St. Louis ragtime. But more often, he was there to listen to others play and to converse with musician friends, including Louis Chauvin and Tom Turpin. He became a student and friend of Alfred Ernst, director of the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society, with whom he studied classical music. Joplin persevered in his quest to refine and develop syncopated music— ragtime—as serious music, and it was largely his efforts that moved ragtime from the barroom to the white middle-class parlor.

Photo courtesy of Missouri Division of Tourism

During his time in this second floor flat on Morgan Street, Joplin began work on a major, serious composition, an operatic piece called “A Guest of Honor.” Possibly the historic visit of Booker T. Washington to Theodore Roosevelt’s White House inspired it, although Joplin’s opera was reputedly set in the beautiful Missouri Governor’s Mansion in Jefferson City. Sadly, we may never know for certain, since the original score was lost and only a few short passages have been reconstructed. While living on Morgan Street, he also published some of his most successful rags: “The Entertainer,” “Elite Syncopations,” “The Strenuous Life,” “March Majestic,” and “Ragtime Dance.” Buoyed by his royalties on these pieces, he left Morgan Street and moved to a larger house on nearby Lucas Avenue in 1903. There, he might have even become the landlord to several other ragtime musicians who listed the same address. Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden, former students of Joplin’s in Sedalia, also had moved to St. Louis and may have lived with the Joplins for a time. Both later coauthored rags with Joplin, and the teacher and his former students became the exemplars of Missouri ragtime.

Joplin was in and out of St. Louis for a few more years, spending time in Sedalia and Chicago, and he enjoyed continued success. New compositions included some of his most popular, among them “The Cascades,” a musical tribute to the beautiful waterfalls at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. He continued his quest to transform classical music to embrace folk and rag themes, and he probably began work on a second opera, “Treemonisha.” In 1907 he moved to New York, where he struggled for years to get his completed second opera performed. He finally produced a trial performance of “Treemonisha” without scenery or orchestra at his own expense. Sadly, it was a disaster and a serious blow to his spirit—he never really recovered. Obsessed with the opera and weakened by disease, he entered the state hospital, and he died there on April 1, 1917.

The decades after Joplin left were not kind to this area of St. Louis, and the post-World War II era of so-called projects and urban renewal devastated large swaths of the old declining neighborhoods. In the 1950s and 1960s, many of the properties along Delmar Boulevard had fallen into serious disrepair. By 1977 the derelict building at 2658 Delmar was the last remaining structure anywhere known to have been associated with Scott Joplin. The cradle of his most productive and successful period, it was designated a National Historic Landmark. Nonetheless, it had the misfortune to be located in a part of St. Louis that was slated for complete obliteration and transformation for commercial or light industrial uses.

After its landmark designation, Jeff-Vander-Lou, Inc., a not-for-profit neighborhood development corporation, purchased the house and led the charge for preservation. The St. Louis Board of Aldermen eventually appropriated $100,000 for restoration, but the money was tangled in controversy for years. Finally in 1983 after complex negotiations, Jeff-Vander-Lou donated the building to the state for restoration as a historic site.

By the time the transfer was made, time and vandals had nearly destroyed the building while it stood empty. A squatter had built a campfire in the center of the west duplex parlor floor, and the fire burned through two floors and part of the roof. On the east side of the duplex where the Joplin flat was located, the building was in better condition, but a failed roof had caused water damage to paint, plaster, and woodwork. Extensive and expensive restoration over a period of several years gradually returned the duplex to its former appearance.

A new opening in the brick common wall between the duplex sides allows visitors access to both sides through one entrance. The ground floor of the west unit contains exhibits explaining the history of the house, its restoration, and the neighborhood. On the second floor of this west unit are offices and a small archive room. On the east side, one finds more exhibits about Scott Joplin and his music and a room housing an authentic, operating player piano and a large collection of piano rolls, some actually cut by Joplin. With these rolls, you can listen to Joplin’s personal style of playing ragtime. If you’re good enough, you can even play a duet on the player piano with Scott Joplin himself—you get to use all the keys he’s not using!

Photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks

Visitors can pass through an opening in the thin boarding that had enclosed the staircase and climb the stairs into a world of turn-of-the-century St. Louis. Lit only with gaslights, the flat where Scott and his new wife, Belle, set up housekeeping is small, with a parlor, a bedroom, and a small kitchen at the back of the house that in grander days had been a maid’s bedroom. The flat is provided with period furnishings—used, a little worse for wear, but not junk, befitting Joplin’s status as a struggling musician just at the beginning of better times. It seems only right that the flat has a piano, but it isn’t known for certain if Joplin was able to afford his own at this time.

As the Joplin house was being restored, the red brick neighborhood surrounding it was rapidly disappearing as the land clearance authority razed building after building. The Joplin house seemed in danger of becoming lost in either an open greensward or a sea of new manufacturing plants, neither of which would convey much sense of the old urban neighborhood that Joplin knew. To protect against a total loss of context, park officials bought the buildings on either side of the Joplin house and several nearby row houses for preservation. Vacant lots in front and behind were purchased to keep new construction for manufacturing firms at a respectable visual distance.

The commercial building on the west side of the Joplin house was rebuilt as the New Rosebud Café, a replica of the bar and gaming club that Scott Joplin frequented. It provides an authentic performance space for ragtime concerts and other special events, and arrangements can be made to rent the New Rosebud Café as a venue for private parties. The sound of syncopated piano frequently reverberates through the building, and there is an occasional cakewalk dance. The site also hosts lectures on African American life in St. Louis in the early 1900s. The building on the east side of the Joplin house is being used as state park offices. Several other period buildings have been stabilized for future use.

Today the Scott Joplin State Historic Site attracts a variety of visitors, from local school groups learning about life and music in early 1900s St. Louis to out-of-town musical groups to syncopation aficionados, who come from all across America and the world to pay homage to “the king of ragtime.” The site is a tribute to the creativity and talent of an enormously gifted musician who called Missouri home, and it celebrates the many rich African American contributions to Missouri’s cultural history.

SCOTT JOPLIN HOUSE STATE HISTORIC SITE • 2658 DELMAR BOULEVARD, ST. LOUIS

Featured photo courtesy of Brian Stith.

Related Posts

Melodies of Missouri

You will be surprised by some of the songs about Missouri and some of the celebrities who sang them. Our state, its people, and their stories are reflected in these six songs from our past.

Missouri Innovators Improve Daily Life For All

Meet two dozen innovators from Missouri's past and present.