The enduring military publication Stars and Stripes was born in Bloomfield amid the destruction of the Civil War. Visit the Stars and Stripes Museum Library to see the original newspaper, a Huey helicopter, and many other exhibits.

By Diana Lambdin Meyer

Photos by Bruce N. Meyer

It was one of sixteen times during the Civil War that the little town of Bloomfield in the Bootheel switched hands between the North and South. Union forces entered the Stoddard County seat in November 1861, forcing Confederate soldiers south.

As members of three Illinois Union regiments entered the abandoned offices of the Bloomfield Herald newspaper, the destruction of war paused as one of our country’s most powerful and enduring publications was born.

“Some printers belonging to our regtt. and the others have taken possession of the printing office and design publishing a paper tonight,” Captain Daniel H. Brush of the 18th Illinois Infantry Regiment wrote in his diary.

During the night of November 9, 1861, ten men labored over the presses to produce the first edition of The Stars and Stripes. They named the paper for the American flag, and its four pages related the activities of their regi- ments. The paper, with its motto “The Union: It Must and Shall Be Preserved” served as a morale builder among the Northern troops.

One of only three known remaining copies of that first edition is on display at The Stars and Stripes Museum Library at Bloomfield. Of the other two, one is at the Smithsonian Institution; another is privately owned. The Bloomfield museum pays tribute to the publication that today is the daily newspaper of the United States military, with five editions, more than twenty-two news bureaus, and 360,000 readers in forty-eight countries.

BIRTH OF A NEWSPAPER

The first Stars and Stripes grew out of an order from Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant. According to James R. Mayo, president of the museum library association, on November 2, 1861, Grant ordered Colonel Richard J. Oglesby of the 8th Illinois Infantry Regiment stationed at Birds Point to expel from Bloomfield Rebel forces under Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State Guard. Oglesby organized about twenty-two hundred men from the 8th, 11th, 18th, and 29th Illinois Infantry Regiments and started for Bloomfield. Grant also sent forces from Cape Girardeau and Ironton.

Thompson learned of the approaching Union troops and withdrew his men south before the 10th Iowa Regiment arrived from Cape Girardeau on November 7. James O. Hull, editor of the Bloomfield Herald since starting the newspaper in 1858, left with Thompson’s forces, leaving his office, its contents, and printing press behind.

The Iowa regiment occupied Bloomfield until the next day when Oglesby arrived and took charge. A group of soldiers under Oglesby noticed the abandoned newspaper office. That night, ten of them entered the Herald. Among them, seven had experience in printing and publishing, including Charles M. Edwards and Benson T. Atherton, who served as the Stripes publishers, and Walter A. Rhue and R.F. Stewart, who served as editors.

By the next morning, Saturday, November 9, the group had produced the first edition of The Stars and Stripes. It is unknown how many copies of that first edition were printed, but they were hand delivered to Union troops in and around town.

ROUGH TRANSITION

Since that first edition more than 140 years ago, the paper has experienced fits and starts. It would not be produced again until World War I. In February 1918, Linn County native General John J. Pershing ordered the reinstitution of The Stars and Stripes to build morale among the American Expeditionary Force. At the conclusion of The War to End All Wars, the weekly paper ceased publication.

On April 18, 1942, The Stars and Stripes came to life again, with soldiers working under fire in a London print shop to produce an issue. Since then, the paper has been published continuously 363 days a year, with circulation during World War II reaching nearly two million.

In April 2003, the paper added a Middle East edition, with thousands of copies printed each day in Baghdad, Iraq.

Through its history, military and political leaders have pressured the paper to become a propaganda tool for the cause of the time. Yet many recognized that the value of the newspaper came from its credibility as an objective source of information. Among them were Pershing and Dwight D. Eisenhower, both of whom issued directives that the newspaper must be by and for the soldier. Many of the reporters and photographers are military personnel reporting alongside the soldiers in the field.

Some of the nation’s most respected journalists have appeared in The Stars and Stripes, including Edward R. Murrow, Ernie Pyle, Steve Kroft, and Andy Rooney. Rooney, an active member of the Stars and Stripes Association, is scheduled to be the keynote speaker at the association’s annual reunion October 15.

HONORING THE PRESS

Although only one edition of the paper was produced dur- ing the Civil War, the museum and library, which opened in 1998, devotes space to the War Between the States. Civil War artifacts accompany an exhibit on the burning of Bloomfield by bushwhackers in September 1864. The library contains a rare twelve-volume Confederate Military History published in 1899 by the Confederate Publishing Company and a 128-volume set entitled The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Confederate and Union Armies published by the U.S. Government.

The museum includes newspaper issues and exhibits from all wars and major military conflicts in which the United States has been involved. It is as much of a journey through world history, culture, and geography as it is the story of a single publication.

Displays include World War I gas masks, D-Day parachutes, K rations from Korea and Vietnam, and burqas from Afghanistan. Unpublished photos by Striper photographers in places such as Bosnia, Kosovo, and Vietnam complement the vivid accounts of soldiers as told by Striper reporters.

MISSOURI CONNECTIONS

Among the newspaper’s biggest controversies, documented in an exhibit at the museum, was when Beetle Bailey was banned from the paper in 1954. A creation of cartoonist Mort Walker, who grew up in Kansas City and graduated from the University of Missouri at Columbia, some felt the Army private character demonstrated too little respect for officers. The flap catapulted the comic strip’s circulation in newspapers worldwide.

St. Joseph native Walter Cronkite’s work has appeared in The Stars and Stripes. Irving Dillard, who worked for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at various times from 1927 to 1960, was a Striper during World War II, and cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for the Post-Dispatch, won his first Pulitzer in 1945 for work in The Stars and Stripes.

A room in the museum honors four southeast Missouri recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. military decoration awarded for bravery and valor in action.

While the museum is dedicated to military history, it and The Stars and Stripes are as much about honoring the First Amendment and freedom of the press. As World War II General George C. Marshall said, the newspaper is “a symbol of things we are fighting to preserve … free thought and free expression of a free people.”

The Stars and Stripes Museum Library is located at 17377 Stars and Stripes Way at Bloomfield. Admission is free. Hours are 10 AM to 4 PM Mondays and Wednesdays through Fridays, 10 AM to 2 PM Saturdays. For more information, visit NSSML.org or call 573-568-2055.

Read more about the Stars and Stripe Museum Library here.

Article originally published in the October 2005 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

Missouri Synod was Founded

On February 8, 1839, on Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church was founded.

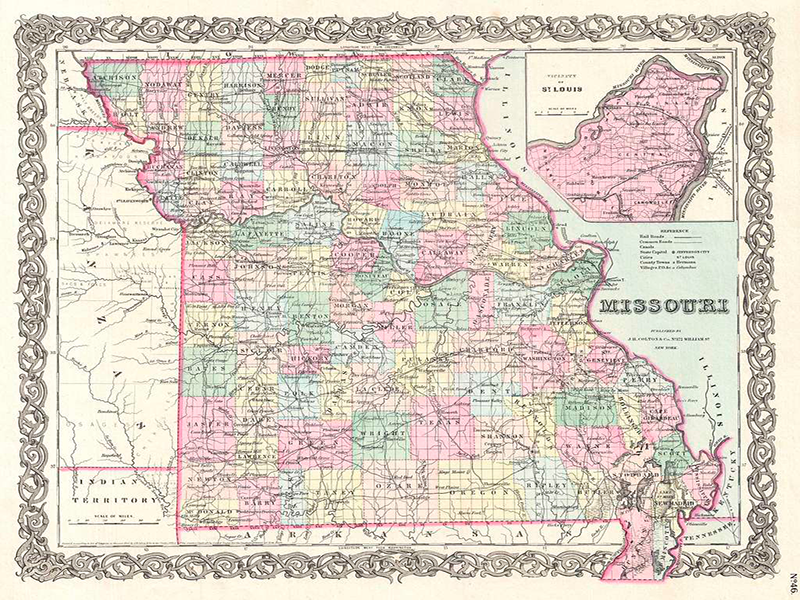

Missouri Counties Formed

On January 2, 1833, new Missouri counties, including Carroll, Clinton, Greene, and Lewis, were formed on this date.

108 Missouri Wineries

On December 11, 2012, state officials announced that there were now one hundred and eight commercial wineries operating in Missouri.