The Missouri Monster—Mo Mo—became part of Missouri history and folklore 50 years ago in July 1972. While I never had an encounter with that Mo Mo, there was another, different Mo Mo that actually lived with us. Let me explain.

After my dad died from COVID in October 2020, I penned a memorial that listed 10 of my favorite memories of time I spent with Jodie E. Jackson Sr., my dad, pastor, and fishing/hunting buddy. Among them was this entry:

August 1972, Meramec State Park near Sullivan, at some point during a church, family, or scout outing – that detail is unimportant – a small group of folks gathered at the riverbank, stunned at the sight of a gigantic footprint in the sand. I remember just one footprint, but supposedly there were two; might have even been bits of fur or hair nearby.

This was almost exactly 100 miles due south of Louisiana, Mo., where the Missouri Monster—Mo Mo—had been spotted a month earlier. Not surprisingly, someone at the outing at the bank of the Meramec River commented about the tell-tale Mo Mo stench. And sure enough, a rank odor filled the air at that very spot. One of my buddies said he’d discovered a dead carp just a few feet away, which was also super-cool to 9-year-old me, but that didn’t matter.

Of course, the footprints were no doubt left by Mo Moo. I asked Dad if it was true. “Must be,” he said with a matter-of-fact shrug. And that was good enough for me.

Not long after, we got a new dog, a little something-pooh pup that Dad named “Mo Mo.” A few years later, Mo Mo had puppies and I claimed the runt of the litter: My “George.”

On the rare occasion that anyone mentioned the Missouri Monster over the next several years, I had my dad’s same matter-of-fact expression and announced, “Cool. I had one of Mo Mo’s babies as a pet.”

Try to tell me that wasn’t true.

My most recent Mo Mo and bigfoot research seems to make it clear that Mo Mo and bigfoot are two distinct creatures, whether real or imagined—and there’s overwhelming evidence that Mo Mo, at least, was a hoax, which doesn’t discount that then 15-year-old Doris Harrison saw “something.” (Here’s the Mo Mo story I wrote for the July/August issue of Missouri Life magazine. The story gives a more comprehensive telling of the Mo Mo tale).

For starters, Mo Mo was described as having “red, glowing eyes,” though that was a subsequent report to Doris Harrison’s initial telling of seeing a foul-smelling beast that was so hairy you couldn’t see its eyes.

Now my bigfoot knowledge is vast, but certainly not comparable to William Magee (more about him later). So whether you call it Bigfoot, Sasquatch, Yeti, the Beaman Monster, the Ozark Howler, the Foulk Monster, Blue Man, or any sundry other hide-and-seek champion bigfoot-like creatures with some standing in Missouri folklore, all of those legendary beasts don’t have glowing red eyes. (That I’m aware of.)

But I’m eager to stand corrected. (Send your bigfoot sightings, reports, and experiences to me at [email protected].)

I hadn’t heard about the Beaman Monster until recently when one of the Missouri Life ambassadors mentioned the legend at an ambassador luncheon in Warsaw. Beaman is just eight-plus miles northeast of Sedalia in Pettis County, in an unincorporated area where just about any kind of wild beast—even a cryptid?—could hide out.

As the story goes, a circus train derailed in that area in the first decade of 1900, and a 12-foot-tall gorilla escaped. I’ve read that some thought that the Beaman Monster was a hybrid offspring, either sired or birthed by the train crash gorilla, but that only accounts for half of the equation. What sort of creature was the second party to the, um, joining of beasts that created the Beaman Monster?

Gorilla meets Mo Mo? Hmm?

Let me now retreat from my tongue-in-cheek treatment of this topic to explain that, like Fox Mulder from The X-Files, “I want to believe.” When I began reporting and outlining the Mo Mo story, I sought out sources on a couple of Facebook pages dedicated to “Bigfoot Research.” I promised that I wasn’t seeking to make fun, though I was pleased to meet and exchange messages with Bigfoot believers who were able to make light of their passion

Before we go much further, it’s also important to point out that the Mo Mo sighting(s) of 1972 had some connection—possibly—with an incident the previous summer north of Highway 79. It’s another oft-told story in Mo Mo lore that two women were having lunch at a rest stop when they were approached by a hairy creature that eventually stole at least one of the sack lunches. The story’s a bit more involved than that, but that’s the gist.

I’ve now had the opportunity (not always taken) to redirect storytellers who get the 1971 and 1972 incidents confused.

“I think it’s compelling half-a-century later because there is still that mystery and intrigue,” says Brent Engel, a Pike and Lincoln county historian and co-president of the Louisiana Area Historical Museum. “There are no answers. There weren’t then There aren’t now.”

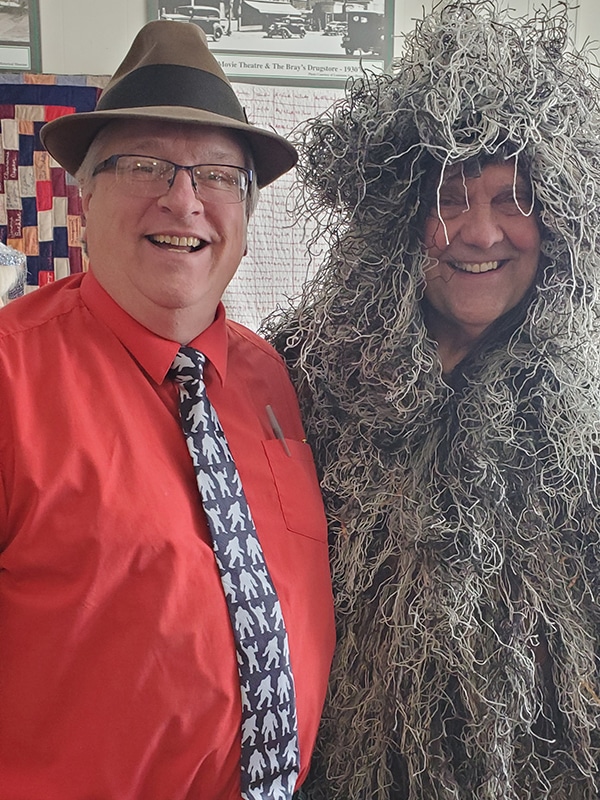

For folks like William Magee—when it comes right down to it—”You can tell me I’m full of crap all you want. I know what I saw.”

What did he see?

In 1991, William spied a creature—about seven feet tall, somewhat “hunched,” and covered with black-brown hair—squatting at the edge of a creek on his property outside Bowling Green, Mo. There was a brief moment of eye contact; the creature’s face was “more human than primate, not ape-like,” he recalls.

In an instant, he says, the creature—which the Magee family now refers to as “Mo”—leaped straight up and over the roughly eight-foot-high creek bank.

“It could have been a split-second. It could have been 20 minutes,” William says. “You’re looking at something you’re told doesn’t exist. But it’s looking at you.”

When William first told me about his encounter, we were on a Zoom call. There was a foot-and-a-half of snow on the ground on his farm, but William was at Pearl Harbor, Oahu, working a humanitarian mission to contain and clean a fuel leak from a 100,000 gallon Word War II tank. William, 51, is an aviation boatswain’s mate and aircraft mechanic with the Navy Reserves.

“I love it,” William says of his work. “I get to play with the fun toys and travel to some neat places.” It’s as if expected me to check his credibility, but he was eager to explain that he’s not a crack-pot—and didn’t really care if I thought he was.

“I’ve seen this thing with my own eyes,” William says, getting back to the topic of bigfoot. “Had I not seen it with my own eyes, I’d be a little skeptical.”

In addition to hearing mysterious “knocks” in the night—bigfoot seekers say the creatures communicate via hitting rocks or sticks on trees—or finding stacked rocks or randomly felled or crossed tree limbs (supposedly signs of bigfoot territory markers).

“Maybe it was Mo,” he says, referring to Mo Mo, Bigfoot, or whatever it is. “In the family, we actually kind of joke around about it. ‘Mo must be back there tonight.’ It’s gone from something to be a little scared of to being a term of affection.”

His side-gig—the serious hobby of cryptozoology—gets a bit of an unexpected boost from his Naval service. He’s part of the Navy Honor Guard that occasionally travels through Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, and Tennessee.

“There’s probably no little town in Missouri I haven’t been in doing some kind of funeral or retirement service,” William says.

Even though Mo Mo fever dimmed over the years, William is not discouraged, adding that in 2007 he solidified his connection to the property that generated multiple generations of bigfoot encounters.

“I became obsessed enough with it,” he says, “that I built a house right here.”

He figures his Mo is some sort of primate, “Something that hasn’t been discovered. A weird mutation. A Neanderthal-type that didn’t go extinct.” His tone is a mix of statement and question.

When I drove to visit William at his farm and to take a four-wheeler ride to the spot where he saw his Mo 31 years ago, the backroad from Louisiana featured shifting shadows and the kinds of rural Missouri scenery that I’ve been accustomed to all my 58 years.

“If I had wanted to see something,” I told William … And before I can finish, he says it. “You would have seen something.”

There’s something to be said for emotional contagion or catching someone else’s imagination and running with it. For instance, William says he knows a former radio deejay and producer who “made up reports to keep the story alive” during the Mo Mo frenzy in 1972. “Eighty percent of the reports from the ‘70s were them making it up.”

That’s kind of a bummer for Bigfoot researchers like William, who separates himself from other “researchers” who claim that title because they’ve found a bevy of YouTube videos or social media groups that reinforce what they already believe—or want to believe—about cryptids like Bigfoot without applying some scrutiny to the information.

“I’ve heard some crazy theories. But I don’t dismiss them,” he says. “Maybe there’s a part of that crazy theory that explains what’s going on.”

Back in 1972, Conservation Agent Gus Artus led a detailed, three-hour search of 100 acres in the area where Mo Mo was reportedly seen. He told reporters waiting for groundbreaking bigfoot news, “I am convinced, and the rest of us are also, that there is nothing that even looks like a monster on Marzolf Hill.”

Still, sightings continued, with a mix of supernatural and paranormal phenomenon occasionally added. For one, there were reports of different colored fireballs or lights in the sky over Marzolf Hill. That spurred a UFO enthusiast, Haden Hewes of the International Unidentified Flying Object Bureau of Oklahoma City, to travel to Louisiana and camp in the Harrison’s backyard. Although Hewes didn’t find evidence of Mo Mo, he posited the theory that Mo Mo had been left in the area by UFOs or was, perhaps, a sort of Neanderthal creature.

I should note here that when I requested sources for my Mo Mo/Bigfoot story, I asked that UFOs, paranormal activity, government cover-ups (they know they’re out there), and those sorts of explanations not be part of the conversation.

The bigfoot legend has a stronger hold on upstate New York and the Pacific Northwest, but it also has regional connections throughout the Show-Me State, from Mo Mo to the Big Muddy Monster, the Ozark Howler, Wood Ape, and the Foulk Monster. Native Americans, including the Osage in Missouri, and explorers as far back as the Vikings reported seeing unidentified beasts through what is now America and its heartland..

Besides, says Joe Jerek, MDC spokesman, Missouri does have “some amazing animals” that don’t get much attention but spark the imagination. There’s a freshwater jellyfish—that’s right, a species of jellyfish—that occurs throughout Missouri. And there’s the seldom-seen hellbender, Hercules beetle, lampreys, and other critters that look like something from another world.

But … “there’s absolutely no scientific evidence of bigfoot or the Missouri Mo Mo,” Joe says.

William says that’s not convincing because “for years the Conservation Department said there weren’t mountain lions in Missouri, and a lot of us were seeing them.”

That’s a different matter to the MDC, though, because mountain lions are a known species and the department has confirmed 100 mountain lion sightings dating to the 1990s. There’s even a mountain lion reporting page at mdc.mo.gov.

“We still don’t have any clear or firm evidence of mountain lions breeding in the,” Joe says. “We readily, and fully acknowledge, that there are mountain lions in Missouri.”

What about black panthers—mountain lion, cougar, puma, painter, whatever they’re called these days?

A lot of folks—William Magee included—have said they’ve seen black mountain lions or have seen wildlife trail camera photos of them. And here’s where the back and forth closely resembles the real vs. not real discussion about Bigfoot.

“Actually, the only large black cat on Earth is the black leopard that lives in India or Africa,” Joe says. “There’s no evidence of black mountain lions anywhere in North America. Believe what you wish, but there is no evidence. That would be great if there’s some evidence.”

Related Posts

Made in MO: Pop Art

A glowing pink popsicle highlights the new sign of an innovative dessert shop in downtown Branson. Since opening Mainstreet Pops (formerly Dreamsicle’s) in 2017, Brooke and Rodger Jones have cultivated a bright, energetic atmosphere with colorful decor that matches their festive frozen treats.

Listen to the Second Episode of Mo’ Curious by Missouri Life!

In our second episode, we delve into the history of communes and utopian communities in Missouri.

The First Episode of Mo’ Curious by Missouri Life is Here!

In our first episode, we explore Missouri's geologic history stretching back billions of years to the formation of the Ozark Plateau. Hear from experts as we journey through geologic time to better understand the way that our geologic landscape has shaped the way we interact with our state today.