Missouri is the cave state. This state park is one you should not miss. For more than seventy-five years before its 1982 acquisition as a park, Onondaga Cave was one of the major public attractions in the Midwest, and it still is. Come see why!

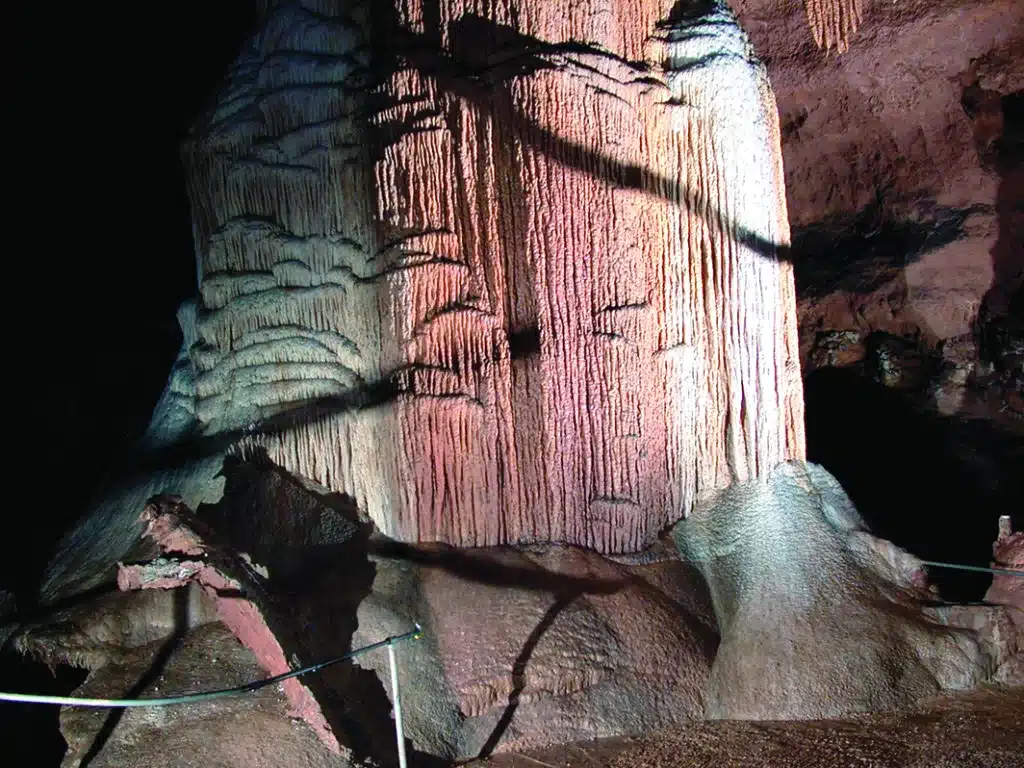

flowstone, which formed as water flowed down the wall.

Photo credit: Photo by Eric Spradling

THE CROWN JEWEL IN MISSOURI’S underground treasure chest is Onondaga Cave. Meramec State Park, just twenty miles downstream, has the greatest number of caves, but Onondaga Cave State Park has the preeminent cave.

More than a geologic curiosity is preserved at Onondaga Cave State Park. Here is a memorial to a disappearing style of roadside showmanship that is peculiarly American. It is impossible to separate Onondaga Cave, the natural phenomenon, from Onondaga Cave, the showplace of a vintage twentieth-century frontier-style capitalism. The colorful cave forms are the results of millions of years of geologic history, and the human story of the cave is every bit as colorful. Appreciation of this state park in Crawford County is greatly magnified by knowledge of both.

More than thirty known caves are in this 1,300-acre park, more than any other park except Meramec. Two are well-known, Onondaga and Cathedral, and both had long histories of commercial operation as show caves. They occur in separate forested ridges divided by two small but deep valleys and a third ridge with nearly three hundred feet of relief.

Photo credit: Photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks

The geologic story of these caves is like that of many others in the state. In prehistoric times, much of what is now Missouri was inundated by a series of shallow, warm seas. Over millions of years, shells and exoskeletons from a whole host of aquatic plants and animals were deposited as layer upon layer of sediments. Ages passed, and these deposits became the limestones and dolomites of the Ozark Plateau. The Paleozoic seas receded, and the land rose upward. Groundwater, which had become mildly acidic from percolating through decayed organic material on the new dry land, found its way along cracks and within the horizontal seams separating the sedimentary rock layers. The water slowly dissolved away the calcareous material, forming larger cracks and, finally, tunnels and chambers.

While this subsurface rock was being dissolved by groundwater, surface runoff began to cut valleys forming the Ozarks we know today. As the valleys deepened, the water table dropped, and some of the water-filled tunnels drained. As air replaced water in the passages, they became what we know as caves—like Onondaga and Cathedral. The mouths of the caves are the points where valley streams have cut across the passages, opening them to daylight. But the work of water was not done. Streams within the caves continued to erode both stone and clay fill, enlarging the cave passages and finally emerging as springs at the cave mouths.

Water carrying dissolved minerals from the ground could also seep into the caves, frequently depositing carbonate rock forms known technically as speleothems, or more familiarly as stalactites (hanging from the ceiling) and stalagmites (rising from the floor, due to drips from above). The color and variety of these dripstones and flowstones lend a decorator’s touch to the cave interiors. Cave formation is an almost magical process: water dissolves and erodes the rock, forming the caves, and water can eventually fill the cave back up with redeposited stone.

No one really knows when the first explorers entered Onondaga Cave where its spring exited, but this entrance area was host to several mills during the latter half of the nineteenth century. In 1886 Charles Christopher, John P. Eaton, and Miles Horine began exploring what was then called Davis Cave, after William Davis, who owned and operated a mill at the spring and had built a dam to create a millpond at the cave’s entrance. Eaton and his friends used a johnboat to gain entrance. Later, Eaton and Christopher acquired several hundred acres north of the Davis property, land under which much of their beautiful discovery was located. Plans were made to mine the cave onyx (calcite flowstone) from the plentiful formations, but lack of mining expertise and funds forced them to sell their holdings after the turn of the century.

Photo Credit: Photo by Paul Nelson

One of the buyers was a St. Louis man, George Bothe, who formed a mining company to remove and market cave onyx for use, among other places, at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. But a number of factors, including the brittleness of the calcite when removed from the constant cool temperature and humidity of the cave, led Bothe to look for some other way to exploit his underground treasure. He advertised the cave as an attraction for fairgoers, and he arranged for them to ride there from St. Louis on the Frisco Railroad, in which he had also invested. Thousands of visitors rode the Frisco to the little town of Leasburg where they were met by surreys or wagons for the five-mile trip to the cave. The success of the cave as a fair attraction convinced Bothe to keep it open for public viewing. He acquired the mill property from William Davis’s widow and promoted the cave in railroad literature.

An interesting aspect of the ownership of caves is that owning the entrance to a cave is not the same as owning the cave: the cave belongs to whoever owns the land it is under. The sprawling nature of the Onondaga Cave system and a lack of knowledge in the early days about its extent led to what would be a long and convoluted struggle over ownership. After the Bothe ownership, there were no less than a half-dozen owners, even including a St. Louis hospital, often with rival and competing claims to the land above the cave. A separate entrance was used to develop what was called Missouri Caverns—in reality, just a different portion of the same cave. There were cave wars above ground in the courts and below ground in the cave. Rival owners’ cave guides sometimes engaged in rock throwing across the barbed wire fences that divided some passages of the cave, while above ground, roadside hucksters attempted to lure unsuspecting tourists to competing attractions. Legal action proceeded all the way to the Missouri Supreme Court. The cave wars finally ended in the 1940s, when the Crawford County Caverns Company acquired ownership of all the competing claims.

In 1949, Onondaga Cave began its ascent to national notoriety when it was sold to Lyman Riley and Lester B. Dill. Under their leadership, Onondaga reached its commercial apogee in the 1950s and 1960s as a nationally known show cave. Dill became sole owner in the late 1960s, and his remarkable personality has left its indelible mark on Onondaga Cave and Missouri’s tourism industry. Dill had an Ozark wit and a legendary gift for telling tall tales. He always told what he called the Ozark truth—something between the honest truth and a bald-faced lie—like the time he promoted a 102-year-old Oklahoman named J. Frank Dalton as the real, still-living Jesse James. His stubborn resistance to the Army Corps of Engineers helped save the cave and much of the surrounding Meramec River valley from permanent flooding by the proposed Meramec Dam.

Lester Dill became known as “America’s Number One Caveman,” but he always referred to himself as a “caveologist.” He had started exploring caves as a young boy giving torch-lit tours of Fisher Cave in Meramec State Park, where his father, Thomas Benton Dill, was a former landowner and the first superintendent. In 1933 Dill bought the old saltpeter Cave near Stanton and turned it into Meramec Caverns, set in what he called La Jolla Natural Park. Dill took the idea of highway advertising and set a standard for cleverness and saturation rarely equaled on the nation’s highways. Billboards and painted barns heralded “See Jesse James’ Hideout—Meramec Caverns” and “Visit Onondaga Cave, Daniel Boone’s Discovery.” He was instrumental in founding the National 66 Association to promote tourist attractions along old Route 66, dubbed the Main Street of America.

In 1980, Onondaga Cave won designation by the National Park Service as a National Natural Landmark, a testament to its value to science and to Dill’s respect for the natural integrity of the cave despite his marketing prowess. Even before his death that same year, Dill had already begun talks on turning Onondaga Cave into a state park. With the co- operation of the Dill estate, the Nature Conservancy, and the Missouri legislature, his desire to preserve Onondaga for future generations was at last realized with the dedication of Onondaga Cave State Park—and presentation of the national landmark plaque—in 1982.

Shortly after acquiring Onondaga, park system scientists began working closely with the concessionaire and park staff to develop a cave stewardship plan. The plan ensured that the public would continue to enjoy the cave while its delicate biota and fragile geologic treasures were preserved. For decades, countless thousands of visitors had caused physical damage to natural features and cave organisms—not maliciously but through lack of knowledge. New corrosion-resistant metal railings were installed along walkways, and new lighting circuits with low-intensity lights reduced the unwelcome green algae that covered areas around the old lights. The Missouri Speleological Society and other groups of cavers volunteered to remove trash and debris brought into the cave through the decades, thus reducing chemical contamination to groundwater. The practice of tossing coins into the pools in the unique lily-pad room was prohibited; cave guides were trained to explain how this activity had disrupted the delicate chemical process that formed the stone lily pads. Smoking was prohibited to eliminate air pollutants harmful to cave life. Unneeded shafts once used for transporting gravel into the cave were sealed, and airtight entry doors were installed to restore natural air currents, humidity, and temperature and to prevent drying of the cave.

Photo Credit: Photo by Scott Myers

In 1983, after deauthorization of the Meramec Dam, the Army Corps of Engineers added to the park another 380 acres downstream, including a large dolomitic bluff, the tallest bluff on the Meramec River. Many a canoeist is awed by the hulking dark-stained cliff face of Vilander Bluff with its projecting overhangs looming above. Along its rocky, broken slopes and atop the 250-foot cliff, eastern red cedars grow in timeless fashion. Seventy of them exceed three hundred years in age, with some up to five hundred years old. Dislodged skeletons of these ancient trees lie scattered here and there at the base of the cliff, their extremely slow decay allowing dendrologists to study the effects of bluff weathering on the trees.

Beware. Below the cliff is no place to camp. Cross sections of the base of these deceased cedars reveal scar wounds interrupting the tree rings about every six years, on average. The cause? Falling rocks.

A 206-acre portion of this tract was designated in 1993 as the Vilander Bluff Natural Area; it includes a mile of bottomland forest along the Meramec River, the bluff, caves, and an upland chert woodland and savanna that are accessible by trail.

Missouri celebrated 1990 as the “Year of the Cave,” when its five-thousandth cave was officially recorded. Gov. John Ashcroft proclaimed Missouri “The Cave State” and urged Missourians to become aware of the fascinating mysteries and wonders underground. This proclamation aptly coincided with the dedication of an attractive new visitor center at the entrance to Onondaga Cave, which contains elaborate exhibits explaining Missouri’s underground wonderland. By 2015 Missouri had nearly seven thousand known caves, and Onondaga is still preeminent among them.

Park staff recently discovered yet another passage in Onondaga, which added 310 feet to the known cave. The new addition contains remains of several ice age animals, further contributions of the cave to scientific discovery. In the mid-1990s, the park took over the former concession operation, and its naturalists and interpreters now lead cave tours. And then in 2012, the park attracted thousands of people to a Missouri Bat Festival sponsored by the U-Haul Corporation, at which the firm unveiled what it calls its Missouri SuperGraphic, a gigantic red bat flying over a map of Missouri that would be featured on 1,900 new moving vans nationwide—mobile billboards, in effect—to celebrate Missouri and attract even more visitors to Onondaga Cave State Park.

This National Natural Landmark, saved from fate as a mine by becoming a major attraction at a world’s fair and then surviving as a show cave with creative marketing, still continues to awe park visitors today.

A naming contest in conjunction with the World’s Fair in 1904 settled the cave’s name as Onondaga, which is the name of a tribe of the Iroquois and means “spirit of the hills.”

Photo Credit: Photo by Greg Hanson

RESTORATION SUCCESS

Recently, in the course of removing gravel from old walkways in the cave, park staff uncovered large rimstone dams. The day after cleaning out one such dam, it filled with water, and a grotto salamander had already moved in—instant restoration gratification! On another occasion, volunteers from speleological society grottoes statewide helped relocate and install new bat-friendly gates on Onondaga and Cathedral Caves, which resulted in considerably increased bat numbers within a few years.

ONONDAGA STATE PARK • 7556 ROUTE H, LEASBURG

Read more about other amazing Missouri State Parks here.

To get the book Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites, click here.

Related Posts

Get Out and See Big Oak State Park

You have got to see these trees. Big Oak Tree State Park is home to one national champion, a pumpkin ash, and three state champion trees, overcup oak, sweetgum, and persimmon. The ancient cypress are awe inspiring. The park is also a bird watchers dream with more than 150 known species chirping from the trees.

A True Gem of a State Park

Dedicated in 1938, this gem of a state park now sits amid an expanding suburban landscape and is worthy of a visit any time of year. There are twenty-two CCC-era structures to visit, rocky hills to hike, and massive trees to stop and rest under.

Hiking Graham Cave State Park

Head over to Graham Cave State Park to walk in the footsteps of early Missourians.