The Norton grape being designated as Missouri’s grape flies in the face of its history and origin. Our wine columnist Doug Frost explores this robust wine and guides us to the wineries with the best Nortons, often called Cynthiana.

By Doug Frost, who is both a Master of Wine and Master Sommelier, is one of only three in the world to achieve both titles, which involve strict tasting and sniff tests. He lives in Kansas City. That Norton has been designated as Missouri’s grape flies in the face of its history and origin. At first, called the Virginia Seedling (or Norton’s Virginia), the Norton tale begins with Dr. Daniel Norborne Norton (1794-1842), whose vineyard, like others of his mindset, was a playground for the grapevine enthusiast.

It reflected a still undiscovered new world of grapes, fruits, flowers, and all manner of flora. Becoming a childless widower at 28 years of age, he spent the next few years in fitful depression, and he, in his own words, “looked to the grave with pleasure as a retreat from misery.” He would find solace in his farm, as one “who delights to dip his locks in the scented dews of the hyacinth and makes love to the roses and tulips.” Be understanding of his overwrought prose—it was the 19th century, and he was still a young man.

Though a doctor, Norton received more praise for his horticultural efforts than for constantly telling patients to “take one of these powders every two hours in a little sugar and water,” as he complained. His obituary focuses on his efforts with the grapevine, and among his breeding successes was the grape that bears his name, although he did not in fact purposely breed it. Norton appears to be an accidental pollination between the Bland grape (named for its discoverer, not its character … or possibly for both) and one much-contested vinifera grape, and here we can let the arguments fly, but not from me.

It is Norton’s journey through Missouri that pertains. By the late 19th century, there were Norton vines here, though often called Cynthiana (essentially the same grape). By the 1960s, the state was more famed for the grape than Virginia (which still rankles the skilled Norton interpreters there). The prevailing wisdom at the time was for the grape to sleep in the barrel for long periods of time, but the current style of fresh and fruity does the grape more justice.

Indeed, the miracle of Norton is that it can succeed as a rosé, a sparkling wine, a dry wine, a sweet Port, and nearly everything in between. Yet winemakers who coax prettiness from the grape are themselves miracle- workers; Norton has piercing malic acidity that has to be tamed to reveal its charms.

As viticulturalists have noted, Norton is a remarkably robust vine, able to withstand Missouri’s torrid summers and sub-zero winters. It’s that hardiness that has led to the grapevine being used to breed others. To date, Crimson Cabernet (Norton crossed with Cabernet Sauvignon) is the most popular, and it has yielded numerous good wines in the two or so decades since its creation.

Still, it is Norton’s outsized personality that brought it to its current status—talked about, even lauded, but not always loved. The wine it gives can in fact live longer than almost any other hybrid wine, but it also can be vexingly unpredictable. I am not altogether shocked when a Norton that only a few months ago was delicious is suddenly awkward and off-kilter. Experience tells me to be patient and to return later, but that’s not a message consumers may find comforting. Nonetheless, for many of us, a grape with so much individuality is cause for celebration. Norton has few peers, whether in Virginia or here in Missouri, where it seems to have found its permanent home.

Where to seek the best Norton:

• Adam Puchta

• Augusta,

• Dale Hollow

• Defiance Ridge

• Jowler Creek

• Les Bourgeois

• Montelle

• Mount Pleasant

• Noboleis

• St. James

• Stone Hill

To give due credit, some of this information is taken from Todd Kliman’s book about the Norton grape, The Wild Vine, as well as an American Wine Society the article was written by Rebecca and Clifford Ambers.

Related Posts

2020 Missouri State Fair Update

Although this year’s fair may look and feel a little different, the competition, fun, and fair food awaits.

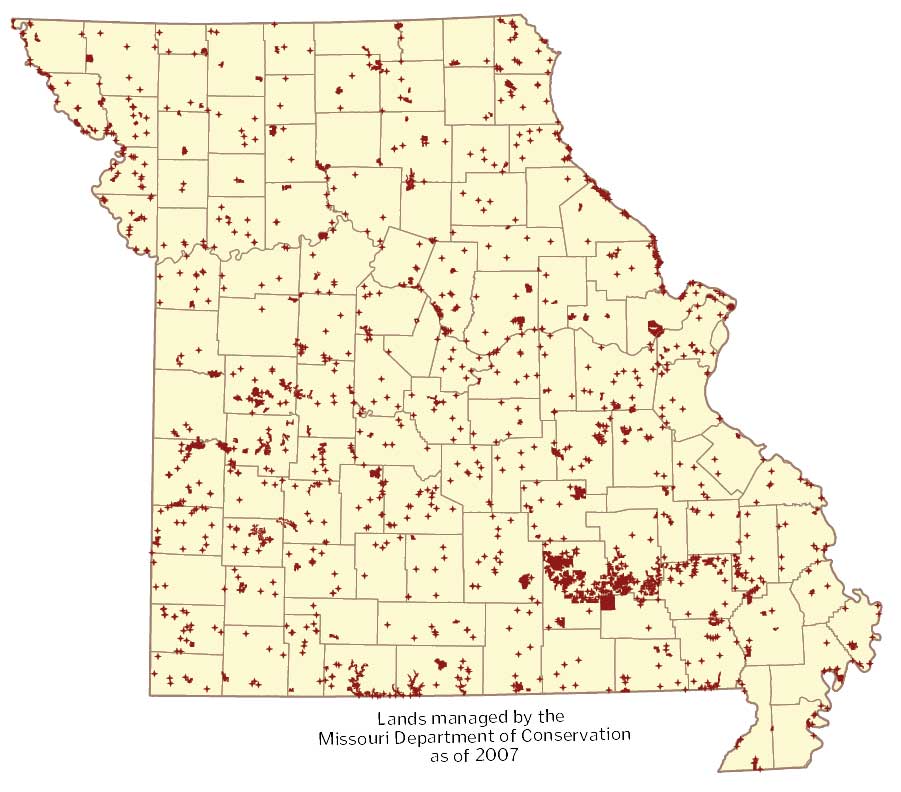

STATE-TISTICS: Conservation Areas in Missouri

Conservation areas by the numbers