Cuivre River State Park consists of more than 6,400 acres centered on Big Sugar Creek, a tributary of Cuivre River. A dozen different hiking, backpacking, biking, and equestrian trails total some thirty-five miles make this park a great place to visit.

Photo by Tom Nagel

THE CUIVRE RIVER barely touches the southwestern edge of the state park that bears its name in Lincoln County. But the juxtaposition is dramatic: a high cliff of Mississippian limestone known locally as Frenchman’s Bluff drops off sharply to the river. From the vantage point of the park, one can take in a sweeping view of the rich alluvial farmland stretching along the valley.

Such striking topography may, at first, seem out of place north of the Missouri River. The rugged landscape, the rich woodlands, the limestone glades, the upland sinkhole ponds: all seem more representative of the Ozarks region south of the river. But Cuivre (pronounced quiver) River State Park is located at the southern end of a sixty-mile stretch of uplifted bedrock known as the Lincoln Hills. While continental glaciers scoured and buried the land north of the Missouri River with debris, the Lincoln Hills somehow escaped most of this. Glacial erratics are found throughout the hills, yet today, the hills remain a biological island with an assemblage of plants and animals not usually found on the glaciated plains of northern Missouri.

The state park consists of more than 6,400 acres centered on Big Sugar Creek, a tributary of Cuivre River; more than eight miles of Big Sugar within the park have been designated by the Missouri Clean Water Commission as an Outstanding State Resource Water. The creek has carved a lovely valley through limestones formed from warm-sea sediments laid down more than 300 million years ago. That ancient sea was home to multi-armed animals called crinoids or sea lilies. Related to starfish and sea urchins, the crinoids once carpeted the sea bottom, and their fossil remains are plentiful in the Mississippian-age rocks exposed in the park. In fact, the crinoid is now the official state fossil.

Eons after the last crinoid died on the seafloor and turned to stone, and long after the resulting rock formations were uplifted, folded, and eroded, the Cuivre River area was inhabited by humans. American Indians arrived in the area as early as ten thousand years ago, and archaeologists have identified their villages, campsites, burial mounds, and ceremonial areas in and around the park. French explorers and settlers came next, hence the names for the bluff and the river: cuivre means copper in French, but some think the river was originally named in honor of Georges Cuvier, a noted French paleontologist and naturalist.

Cuivre River is one of three state parks initially acquired by the National Park Service as Recreation Demonstration Areas (RDAs) through the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act. RDAs were supposed to provide economic and work relief by developing parks from sub-marginal farmland near cities to give urban residents opportunities for outdoor recreation. Most of the forty-six areas acquired nationwide had been badly abused; the lands at Cuivre had been cutover and eroded, with the valleys planted with crops and the uplands grazed by cattle. Two New Deal agencies, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration, built many of the park’s facilities: the roads, bridges, picnic shelter, and group camps. In 1946 the Cuivre lands, along with RDAs at Lake of the Ozarks and Knob Noster, were transferred to the state.

Group camps—Camp Sherwood Forest, Camp Derricotte, and Camp Cuivre—are a special feature of the park. Generations of eastern Missouri school children first encountered wild nature through one of the organized school, church, or other group camp sessions at Cuivre River State Park. Most of the campers came straight from the world of asphalt and concrete. The natural world was new to them. Just as the New Deal was attempting to rehabilitate the lands of the park, so too were the group camps an effort to invigorate the health and imaginations of the young campers.

Camp Sherwood Forest, designed and built in cooperation with the Park and Playground Association of St. Louis, is a perfect example of the traditional New Deal group camp. Fifty-three CCC buildings and other structures still remain, most restored for use. Evoking the Robin Hood theme, the camp consists of four isolated villages—named Ancaster, Locksley Chase, Nottingham, and Fountain Dale—each with five cabins for up to eight campers, two counselors’ cabins, and a unit lodge, outdoor kitchen, and shower house, each accessible from the rest of the camp by foot trails through the woods. Central facilities include a dining lodge, recreation hall, infirmary, and administrative buildings, plus an amphitheater and council circle with a flagstone campfire area and split-log seats. Originally operated under the supervision of the Park and Playground Association (forerunner of the Sherwood Forest Camping Association) with assistance from various social agencies and charities, the camp developed a ritualized program intended to instill the spirit of “friendship, cooperation, and learning” and even more, an appreciation of the workings and values of citizenship in children from the inner city. In recent decades, the camps have been available for rental by a wide range of organizations for everything from religious retreats, group gatherings, and family reunions to music or sports camps, and 4-H, scouting, and school activities.

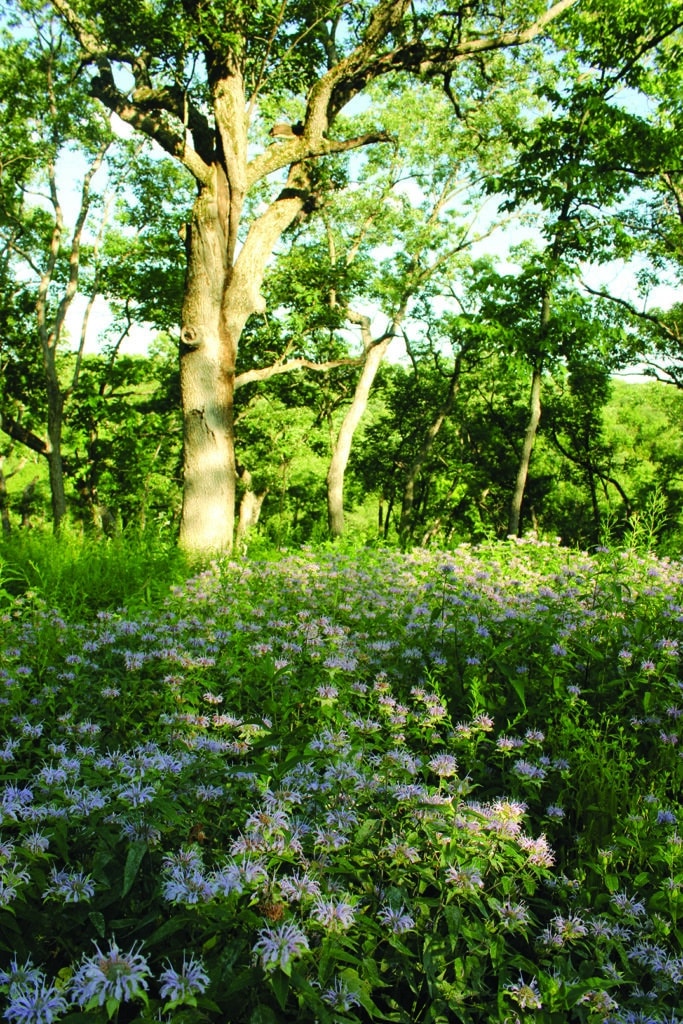

Many woodland wildflowers such as wild bergamot (above) and gray-headed coneflower (below) have responded vigorously to controlled burning and dot the savanna-like border of the Lincoln Glade area.

Photos by Bruce Schuette

Cuivre River State Park, itself an assemblage of restored and preserved natural communities and cultural resources, is an ideal setting in which to learn the meaning of resource stewardship. One might begin with a trip along the main park roads, where the New Deal relief workers in the 1930s painstakingly constructed masonry check dams, curbing, guttering, and culverts to keep roadside ditches from washing out and to direct the flow from one side of the road to the other. Much of this conscientious engineering is now enrolled, along with Camp Sherwood Forest and other structures, on the National Register of Historic Places.

The natural environment has recovered to such a degree that the park now boasts three state natural areas—Big Sugar Creek (56 acres), George A. Hamilton Forest (40 acres), and Lincoln Hills (1,872 acres)—together covering more than 30 percent of the park. There are two state wild areas totaling nearly 3,000 acres, partially overlapping two of the natural areas. Both wild areas straddle Big Sugar Creek—Northwoods is north of Route KK, while Big Sugar Creek is to the south—and both feature a canopy dominated by sturdy white oak.

Big Sugar Creek Natural Area, designated in 1979, extends along and a hundred feet on each side of the northern headwaters of the creek within the Northwoods Wild Area. The creek has a gravel or limestone bottom with a gradient of fourteen feet per mile and is partially spring-fed, like an Ozark stream. However, the springs are intermittent, allowing for warmer water in the pools. The eighteen or more fish species and other aquatic life here show the transition between Ozark and prairie streams. With much of its watershed protected by the park, Big Sugar Creek is one of the least disturbed streams in northeast Missouri. A bot- tomland forest of sycamore, cottonwood, black walnut, box elder, hackberry, and Ohio buckeye grows along its banks.

Toward the southern end of the park along the main road, the George A. Hamilton Forest Natural Area was designated in 1983 and named after an owner who protected this valley before the park was formed. It features a mature white oak forest, one of the finest mature stands in the Lincoln Hills of north Missouri. Abundant spring wildflowers adorn steep limestone slopes that drain into Big Sugar Creek.

In the large expanse of Big Sugar Creek watershed in the middle of the park, a tiny natural area was designated in 1978 to protect Pickerelweed Pond, a three-quarter-acre upland sinkhole pond. By 1997 the natural area had been expanded to the 1,872-acre Lincoln Hills Natural Area—the park’s pride and joy today. Sinkhole ponds are karst topographic features that dot much of the soluble limestone terrain of the Ozarks and this part of Lincoln Hills. Sinkhole ponds have often been misunderstood and abused, whether through drainage, sedimentation, alteration for livestock, or use as convenient dumping grounds. Yet these ponds served—and Pickerelweed Pond still serves—as refuge for some of the park’s rarest inhabitants, like the Missouri park system’s only known population of the beautiful pickerelweed, a planthopper, and a species of bee that feeds only on the plant-hopper; the bee cannot be found anywhere else in the state. For some species like the rare ringed salamander, these ponds provide a breeding habitat at the northern extreme of their global range. Pickerelweed Pond was the one sinkhole in north Missouri that retained sufficient integrity to be designated a natural area in 1978. Park staff have since excavated fill from another sinkhole, one that had been filled in the 1940s to create a playing field, thus reestablishing another rare functional sinkhole pond wetland community.

quiet reflection or exploration.

Photo by Bruce Schuette

Equally significant, as early as the 1970s, park naturalists began a program of prescribed burning, often accompanied by thinning and removal of invasive species, to restore remnant prairie openings, glades, and woodlands characteristic of the area as described by the earliest travelers and surveyors. The first experimental use of prescribed fire by park naturalists anywhere in the state park system was in 1977 on Sac Prairie just south of the road to Camp Sherwood Forest. The prairie still retained long-dormant seed stock of such species as big bluestem, Indian grass, rattlesnake master, butterfly weed, and prairie blazing star, which responded vigorously after the fire. Even more important, where the fire burned into adjacent woods, woodland wildflowers also responded, leading to the landscape-scale use of fire in woodlands not only at Cuivre but elsewhere in the state park system. The park also contains most of the ecologically significant limestone glades in this quadrant of Missouri, and they also were enhanced by prescribed fire after mechanical clearing of red cedar. Since 1977, some 2,000 acres of prairies, woodlands, and glades have been periodically burned under the supervision of park naturalists. More than 60 percent of total park acreage is in special ecological management areas, tracts designated for various types of stewardship or restoration.

The park offers excellent programs and nature walks headquartered at a visitor center with exhibits on the natural and cultural history of the park and the Lincoln Hills. A dozen different hiking, backpacking, bik- ing, and equestrian trails total some thirty-five miles. The trails take you through the wild areas, the natural areas, to Frenchman’s Bluff, and to still other scenic places; you can spend days exploring them. The 50-acre Lake Lincoln is popular for swimming and fishing, and there are numerous campsites and picnic areas.

Photo Courtesy of Missouri State Parks

Even the entrance to Cuivre River State Park is special. Following a narrow corridor of public land north from Route 47, you are gently removed from the asphalt and speed of the workaday world and drawn into the peaceful wooded hills and valleys of Cuivre. When you cross the hand-crafted triple-arched stone bridge over Little Sugar Creek, day-to-day cares seem distant, and you feel somehow reborn. Cuivre River is a park of hope, where nature has regenerated and people may too.

Photo by Bruce Schuette

ONE OF THE MOST BIOLOGICALLY DIVERSE PARKS

Today, Cuivre River State Park is recognized as one of the most ecologically significant and biologically diverse parks in the Missouri system. More than seven hundred species of native vascular plants occur here, seventy-nine of which rank as “highly conservative” species, meaning they are found only in high quality, undisturbed communities of great conservation value.

The entire park is an Important Bird Area, with 190 species recorded, plus more than eighty kinds of butterflies. The park harbors many species at the edge of their range; such species tend to exhibit greater genetic variability and are critical for maintaining biological diversity.

More than twenty species here have not been found in any other Missouri state park—including eight that have not been found anywhere else in the state—and two species are new to science. In the database of species for the entire Missouri park system, Cuivre River has twice as many animal and plant species entered as any other park.

That’s not bad for a park that was acquired as a depleted area, pieced together from more than fifty private holdings in the Great Depression.

Its geologic history and topographic roughness certainly help, as does its proximity to the Mississippi River, which increased the downcutting and weathering of glacial material, exposing preglacial features that created microhabitats attractive to floral and faunal species from both north and south. Its size and relatively long time as a park also help to enhance diversity.

Perhaps the most critical factor has been the decades of active restoration effort here. Several state parks have benefited from long-term stewardship by skilled and dedicated naturalists, but perhaps none more so than Cuivre. Bruce Schuette began here as a summer worker in 1977 and devoted himself to restoring Cuivre until his retirement in 2014. That is rare, and it has made an extraordinary difference here.

The challenge will be to maintain this rigorous attentiveness and care, combined with research and monitoring, in the face of continued threats from invasive species, trampling, and overuse in the most populous area of the state.

CUIVRE RIVER STATE PARK • 678 ROUTE 147, TROY

Related Posts

Get Out and See Big Oak State Park

You have got to see these trees. Big Oak Tree State Park is home to one national champion, a pumpkin ash, and three state champion trees, overcup oak, sweetgum, and persimmon. The ancient cypress are awe inspiring. The park is also a bird watchers dream with more than 150 known species chirping from the trees.

A True Gem of a State Park

Dedicated in 1938, this gem of a state park now sits amid an expanding suburban landscape and is worthy of a visit any time of year. There are twenty-two CCC-era structures to visit, rocky hills to hike, and massive trees to stop and rest under.

Hiking Graham Cave State Park

Head over to Graham Cave State Park to walk in the footsteps of early Missourians.