Take in all of the Civil War history that fills the Anderson House and the nearby 100-acre battlefield. Find out all about the Battle of Hemp Bales and relive what a field hospital was really like.

at the 150th anniversary.

Photo by Scott Myers

THE CIVIL WAR IN MISSOURI is probably best known for the vicious guerrilla warfare that grew out of the cruel divisions among the state’s citizens. Perhaps this degeneration was inevitable given the state’s location and the strong and conflicting convictions of the day, but in the early months of the war, there was some hope that it need not be so. The victors write the histories, often leaving the hopes and aspirations of the vanquished little appreciated. The Battle of Lexington affords an opportunity to ponder the vision and the virtues of the vanquished, who at Lexington were victors for a time.

An important but often overlooked factor of the Civil War in Missouri was the Missouri State Guard. This organization, which never numbered more than 22,000 men at any one time, was mobilized in defense of the state against what the legislature viewed as an invasion by the hostile armies of the United States. This small force, surrounded on three sides by Northern states and contested within the state by Missouri forces loyal to the Union, defended the Southern cause west of the Mississippi River for the better part of a year. The Missouri State Guard was the only border state army to make so bold a campaign, and it did so with little assistance from the official Confederate States Army.

The leader of the Missouri State Guard was probably the most popular man in Missouri. Sterling Price was a Virginia-born tobacco planter from Chariton County who had served Missouri as legislator and governor and his nation as congressman and brigadier general of Missouri volunteers in the Mexican War. His politics were representative of many—perhaps even most—Missourians: he was a conservative Democrat, opposed to abolition but also passionate about the old Union, as he demonstrated when he presided over the state convention in February 1861, at which Missouri decided there was as yet no cause to secede. But when actual conflict came, Price’s Southern loyalty was aroused. He was known for his strong resolve and physical courage, and this was a prime attraction for the men who came to serve in the State Guard.

Price’s rough and ready Missourians won for the South two of its most important victories west of the Mississippi. Except for a small but crucial skirmish at Boonville, he and his men were never driven back on a battlefield. After they disbanded in 1862, Missouri State Guard veterans made up the core of some of the most highly regarded and decorated units in the regular Confederate States Army. Yet today, one can search many standard war histories in vain for any reference to this important force. In many respects, the finest hour of the State Guard was its victory in September 1861 over the federal garrison at Lexington, on the Missouri River. It marked the high tide of hopes for uniting the state behind the pro-South government that Missourians had elected in 1860 and for driving the detested Yankees from the state.

Photo by B.H. Rucker

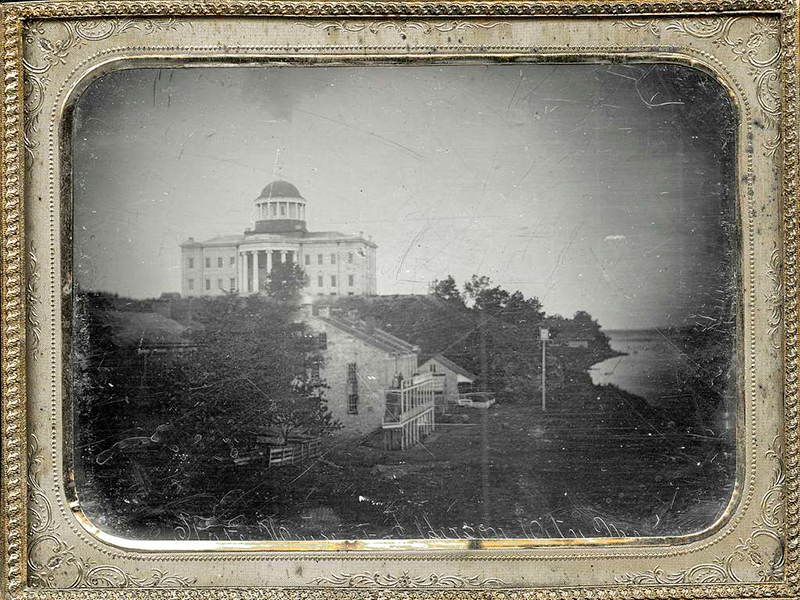

The events leading up to the battle at Lexington had begun in May 1861 when Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson, with authority from the state legislature, expanded and reorganized the state militia to repel a feared invasion of federal troops following the secession of the deep South states. Union forces, composed mostly of local German volunteers, arrested state troops encamped near the federal arsenal in St. Louis on May 10. An ensuing riot resulted in the deaths of twenty-nine civilians fired on by Union soldiers. After observing that riot fi rsthand, Sterling Price offered his services to the governor and was appointed major general of the Missouri State Guard. A federal force composed largely of Missourians, including many German volunteers, moved quickly in June to occupy Jefferson City and other major river towns and rail centers.

Price and the growing body of his hastily called green recruits, along with Governor Jackson and other pro-South state officials, were forced to flee to the refuge of far southwest Missouri, where Price drilled the Guard into a rough semblance of an army. Meanwhile, the pro-Union portion of delegates who had been elected in February to decide the issue of secession reconvened in Jefferson City in July, declared state offices vacant, and elected new officials. Missouri now had two governors—Claiborne Jackson and Hamilton Gamble—and two sets of state officials who claimed legitimacy, a situation that would persist throughout the war.

With the reluctant help of Confederate forces stationed in northern Arkansas, Price’s State Guard advanced in early August toward Springfield, where it met and defeated a Union army under Gen. Nathaniel Lyon at Wilson’s Creek—one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. After this victory, the Confederate units returned to Arkansas, leaving Price and the Missouri State Guard to defend their cause against the now thoroughly roused federal government.

In late August, Price led his army north toward the Missouri River. Flush with the success at Wilson’s Creek, the Missourians hoped to rally the citizenry in the populous pro-South counties of the Missouri valley. They also hoped to open the Missouri River for the many northern Missourians who would rally to the Southern cause but who were prevented from joining Price by Union control of the river crossings. As Price continued northward, his ranks were swollen with new recruits. His march began to seem a triumphal progress and a portent of a reunified state.

Lexington was, and is, a lovely Missouri River town in Lafayette County. In 1861 it was a prosperous trading center for the tobacco and hemp plantations of the area and one of the largest communities in Missouri. It was also strongly pro-South in sentiment, though with a substantial German population in the rural areas. Recognizing Lexington’s importance, federal troops had occupied the town since July, headquartering at the Masonic College campus situated on a ridge that ran toward and overlooked the Missouri River. By early September, the garrison was commanded by a courageous young colonel named James A. Mulligan, an Irishman from Chicago, who strengthened his defenses with an elaborate system of entrenchments and ramparts much too large for his 3,000 troops to defend—an indication perhaps that he anticipated substantial reinforcements.

Photo courtesy of Susan Flader

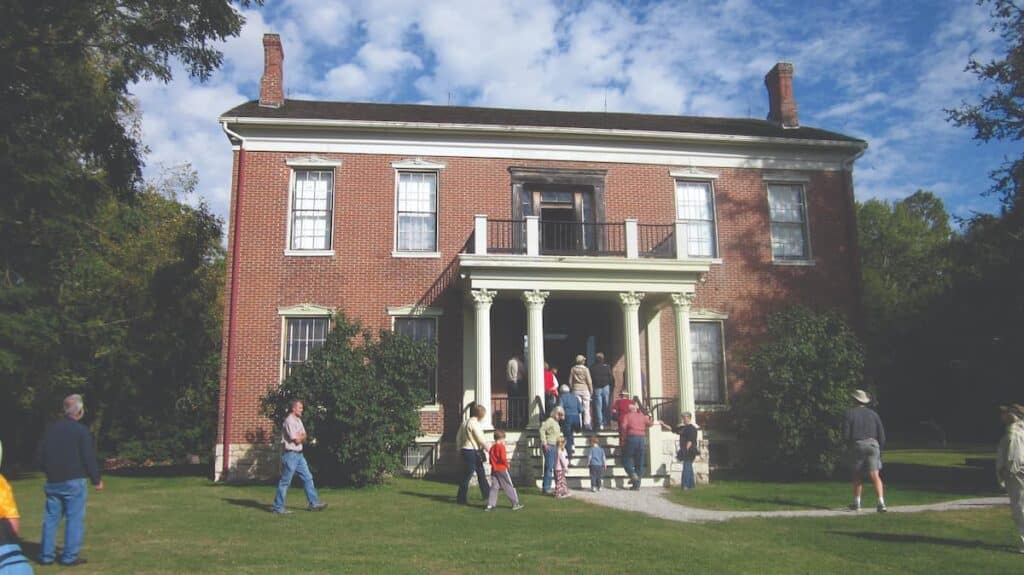

Not far from these defenses was the stately home of one of Lafayette County’s leading families, that of William Oliver Anderson. Anderson owned a factory that processed hemp into rope and bagging, but financial problems led him to serve also as county sheriff. His two-and-a-half-story Greek Revival home had been constructed in 1853 of brick made at the site by slaves. It boasted beautiful millwork, including a handsome stairway of native black walnut, front-porch columns with cast-iron Corinthian capitals, and cast-iron sills and lintels. The property surrounding this fine home with a sweeping view of the river valley included slave quarters, a carriage house, a horse barn, a summer kitchen, a riverside warehouse and wharf, extensive gardens, and an orchard. Married to a cousin of Sterling Price, Anderson refused to take an oath of loyalty to the federal government and was arrested and imprisoned. The house, confiscated by Union troops, was fated to endure bloody turmoil.

Price arrived within sight of Lexington on September 12. The State Guard had grown by now to 12,000 men and was enlarging daily. Mulligan’s federal troops numbered only about 3,500, about half Illinoisans and half Missourians, many of them German or Irish immigrants. After sharp skirmishes on the outskirts of town, Price waited several days for his supply wagons to catch up and then laid siege to the fortified garrison rather than wasting blood and supplies on a frontal assault. “It is unnecessary to kill off the boys here,” he supposedly said. “Patience will give us what we want”—a judgment he might have ruefully recalled three years later after his debacle at the battle of Pilot Knob, which today is also a state historic site.

Once the State Guard was in control of the area, recruits flocked in all the faster. With the arrival of Gen. Thomas A. Harris and his 4,000 northeast Missouri men from across the river, each of the Guard’s nine divisions was represented at Lexington except the first, which was fighting in southeast Missouri. On September 17, Price moved to surround the federal garrison on College Hill and cut off Mulligan’s access both to the river and to drinking water. The siege was on.

With effective blocking of Union lines, the siege warfare took on a casual, almost festive air—at least for those outside the lines. But the bombardment went on night and day, fifty-two hours straight. The reinforcements Mulligan expected never arrived. Most were never sent, but a few were intercepted north of the river by Gen. Mosby Monroe Parsons of Jefferson City and his Sixth Division troops.

The Anderson house, which lay outside the Union entrenchments, was being used by the federals as a hospital. Normally, both sides would have respected the neutrality of such a site. But the Anderson house was in too strategic a location, and it was too far from the regular Union lines to remain unmolested. As a result, it was attacked repeatedly by both sides, as a deep loess gully from the river offered a protected approach almost to the back door. The scars of battle still mark the walls and brickwork of the house, except where a summer kitchen, subsequently removed, absorbed a number of bullets. A bullet may still be found in a piece of door trim, and the path of a cannonball is clearly visible through the attic. Blood still stains the wooden floor of an upstairs bedroom.

Photo by Scott Myers

At length, the Union troops weakened in the heat and drought of the Missouri September. The story is told that when federal soldiers sent some women for water from a spring east of the Union breastworks, the State Guard men allowed the women to drink all they wanted but would not let them carry any water back to the federal troops. Toward the end, Price’s men employed a novel tactic in closing in on the Union entrenchments. They found some large bales of hemp, possibly in Anderson’s warehouse, wrestled them into position, soaked them with water to prevent hot shot from setting them ablaze, and rolled them forward as they advanced, shooting safely from behind them. These innovative movable breastworks functioned well enough to earn the siege the nickname Battle of the Hemp Bales. As the bales approached early in the afternoon of September 20, Mulligan was forced to surrender.

The Union troops had fought gallantly from inside their embattled fort, and Price and the State Guard treated them with no less gallantry. In fact, the Battle of Lexington, besides being the high-water mark of the cause of the South in Missouri, was also one of the last Civil War engagements in which the civilities of old-style warfare were so prominently honored. Price took command of a large store of arms, ammunition, and supplies, but federal officers were allowed to keep their swords. Mulligan and his wife were treated as honored guests in Price’s entourage. All of the enlisted men were paroled after they had been treated to a speech from Governor Jackson reminding them to go home to Illinois and mind their own business, and to one from General Price commending their bravery. Local Union soldiers were released into the community. Commissioned officers were imprisoned at Lexington. The federal entrenchments and State Guard hemp bales kept casualties fairly low, but some sixty-five men in total were killed and nearly two hundred wounded.

In the glow of this victory, the Southern press lionized Price, and the Northern press agonized. Southern sympathizers swelled Price’s army to as many as 22,000 Missourians, a good number of whom drifted away when supplies ran out and hard marching resumed. And hard marching did resume before long when in late September Price withdrew to southwest Missouri in the face of federal forces converging from Kansas and St. Louis. These forces ultimately pushed Price out of Missouri entirely in 1862. Claiborne Jackson headed a government-in-exile until his death later that year. Price transferred to regular Confederate service, and eventually some 50,000 Missourians served in Southern armies. Many other Missourians, of course, followed equally strong convictions into the federal army.

After Price’s withdrawal, Lexington was retaken by federal troops in October and remained under federal control thereafter except for several short-term occupations by Confederate guerrillas or expeditionary forces. Price himself passed through the area again during his unsuccessful effort to retake the state in 1864.

After the war, the town gradually declined in prominence along with the river trade that had led to its rise, but it retained its Southern charm. The Anderson house was purchased in 1865 by the Tilton Davis family, who lived there for the next fifty years; it is their furniture that may be seen in some of the rooms today.

In the 1920s the Lafayette County Court acquired the Anderson house and a portion of the battlefield, and the Works Progress Administration helped to restore the house during 1933 and 1934 in one of the first government-sponsored efforts at historic restoration in the state. The house was offered to the State Park Board as early as 1939, with the thought that the Daughters of the Confederacy would furnish it and cooperate in attracting visitors. Nonetheless, it remained in county hands until its transfer in 1955 to the Anderson House and Lexington Battlefield Foundation, which in 1958 donated the site to the state. A reenactment of the battle on its centennial in 1961 reportedly attracted 15,000 people.

Lexington is brimming with history and still evokes the atmosphere of the antebellum Missouri river town. Even if you don’t have a deep interest in Civil War history but enjoy beautiful Missouri valley scenery, elegant architecture, or an exciting story, you will want to visit Lexington. The contradictions that surround the war in Missouri are many and not easily absorbed, but you will leave with new insights. Maybe too, you will leave with some appreciation for a stalwart body of Missourians who, at the high tide of their soon-to-be-dashed fortunes, proved their capacity to show generosity toward their equally stalwart but vanquished foe. Missouri, and the nation, might not have suffered quite as terribly in the next four years if such antique virtue had continued to prevail.

SEE HEMP BALES AND A SPECIAL SWORD

Today, more than one hundred acres of the original battlefield are preserved in the historic site, including the northern part of the federal entrenchments and the Anderson house. The site offers a self-guided walking tour of noteworthy features and a tour of the house itself, which has been beautifully restored and landscaped to reflect the late 1850s. Visitors are oriented to the site and to the Civil War in Missouri at a visitor center museum and at several kiosks on the grounds. Among featured exhibits in the museum are hemp bales and a special sword. The hemp had to be shipped all the way from China; it was once a leading cash crop in Missouri but currently has stringent licensing requirements. The ornate presentation sword was commissioned by officers under Gen. Thomas A. Harris, who conceived the novel use of hemp bales as movable breastworks. The sword was bought with funds from private donors matched by park funds when it was released from the Augusta Museum of History in Georgia.

Feature photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks.

LEXINGTON STATE HISTORIC SITE • 1101 DELAWARE STREET, LEXINGTON

Read more about the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site here.

Click here to purchase the Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites book.

Related Posts

Missouri History Today December 16, 1964: Wallower Family Departs Missouri Southern State

Missouri History Today December 16, 1964: Wallower Family Departs Missouri Southern State

Missouri State Capitol was Destroyed Again

On February 5, 1911, the second Missouri State Capitol was destroyed by fire. A bolt of lightning hit the dome of the Missouri State Capitol, sparking a fire that tore through the building. Firefighters across mid-Missouri rushed to Jefferson City to try and save the building.

Missouri State Library Established

On January 22, 1829, the Missouri State Library was established in Jefferson City.