The richly diverse Current River State Park features almost two miles of beautiful river frontage, offering ample opportunity for swimming, floating, and fishing as well as hiking, backcountry camping, and interpretive programming.

Photo courtesy of Susan Flader

When Gov. Arthur Hyde and his new game and fish commissioner Frank Wielandy began searching in 1924 for sites to purchase for Missouri’s first state parks, they looked especially at the beautiful springs and riparian forests along the Current and other Ozark rivers. By the end of the year, they had acquired the crown jewels of Round Spring and Big Spring on the Current, Alley Spring on the Jacks Fork, and Bennett Spring on the Niangua. Forty-six years later, all but Bennett were transferred to the National Park Service as part of the deal that created the Ozark National Scenic Riverways. On the Current River, the state park system retained only Montauk at the headwaters—probably because it was a “trout park” with a trout hatchery and rearing facilities run by the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC).

Since then many park lovers have yearned for state parks to return to the Current River. That happened in 2007 when Gov. Matt Blunt approved the transfer of the former Alton Club property on the Current River —just upstream from Round Spring—from the MDC to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The transfer included club buildings plus 780 wooded acres west of Route 19 for a new state park.

Photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks

The property includes a lodge and about twenty other rustic wood structures built in the 1930s as a corporate retreat for the Alton Box Board Company, the largest producer of paper box board in the United States. MDC purchased it in 1996 from a successor firm and operated it as the Presley Education Center, beloved by the many teachers and others who attended workshops and meetings there. But when MDC sought to tear down the old Alton Club buildings and start over with new construction, historic preservationists and river lovers protested that the complex of buildings was a rare intact survival of a type of rustic private retreat once common along Ozark streams. And besides, the buildings were on property under scenic easement to the National Park Service and thus could not legally be replaced. To prove their point, they nominated the Alton Club to the National Register of Historic Places and won approval by the Missouri Advisory Council on Historic Preservation after several tense hearings. The complex of buildings on about thirty-five acres was listed on the register in 2005.

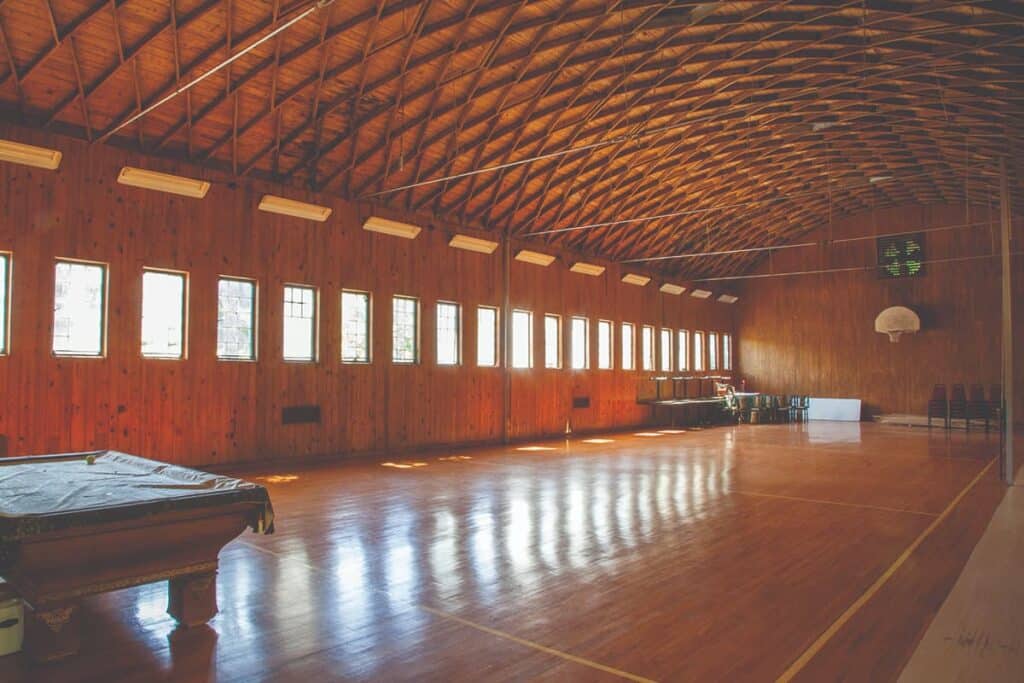

The historic complex in the rustic style common to the National Park Service and to Civilian Conservation Corps structures built in the 1930s includes a lodge with dining facilities, a living room with original finishes (wood paneling and floors and a massive fireplace with stalactites in the stonework), a sleeping wing, and a veranda facing the Current River. Perhaps the most architecturally significant building is a 40-by-90-foot gymnasium with oak tongue-and-groove floor, knotty pine-paneled walls, and a barrel-vault lamella roof designed by St. Louis architect Gustel Kiewitt, a design used also in the old St. Louis Arena, now demolished. Other buildings include a dormitory, a pool hall turned classroom, a screened barbecue house with built-in stone grill, and a lake house that appears to be suspended above the swimming and fishing lake. There was also a tennis court, a skeet-shooting range, and a barn for horses or boats. The thirty-five-acre developed area on the riverfront is landscaped with local limestone and fieldstone retaining walls and walkways.

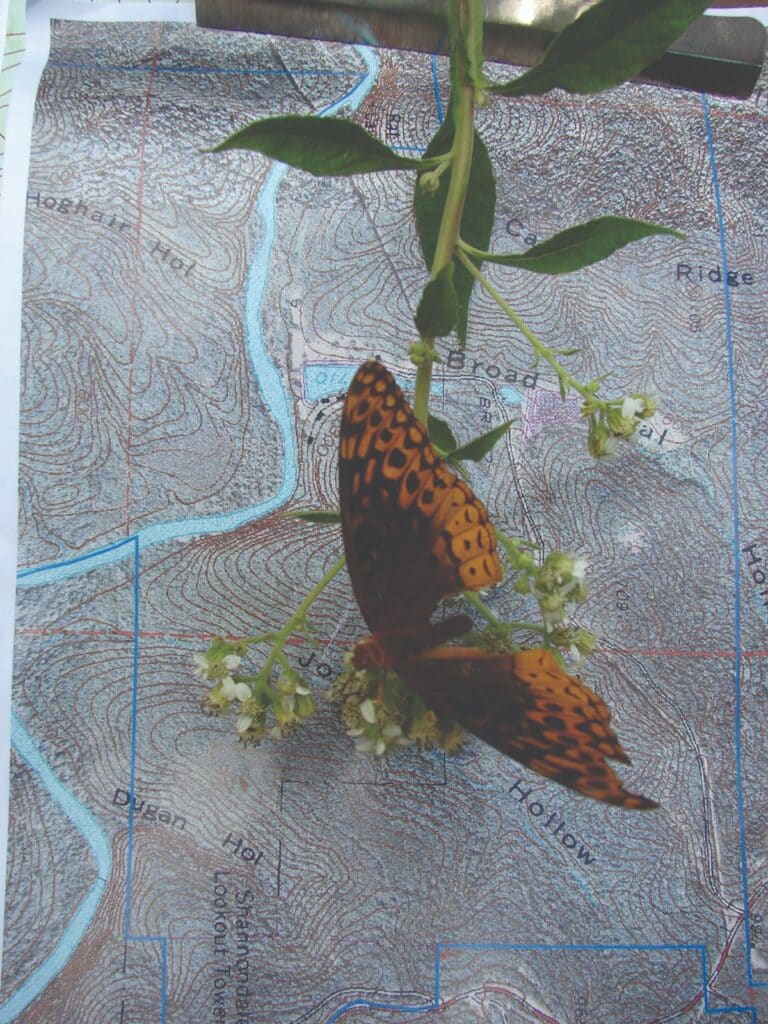

Except for the developed area, the park preserves a remarkably intact and diverse wooded terrain steeply carved through four hundred feet of vertical relief from Route 19 to the river. There are three tributary streams through Broad Shoal, Jones, and Dugan hollows with terrestrial and aquatic communities deserving of natural area status. A fourth stream, through Slick Shoal Hollow on an MDC tract adjacent to the park on the west, is also managed by park staff; the hollow contains an important cave, Bat Cave, a major hibernaculum for gray and Indiana bats. The hillsides are heavily mantled in oak with numerous small dolomite glades, springs, seeps, fens, rock outcrops, bluffs, and bottomland forests, and the bluffs and outcrops expose a broad spectrum of Ozarks geologic history. In the broader sections of hollows are some old farm fields now regenerating, several of which have been planted with short leaf pine. The spring-fed Current River and its tributaries are remarkably clear with high gradients and abundant riffle and bluff pool habitats. The extreme aquatic diversity, physiographic complexity, large expanse of contiguous woodland, and high degree of endemism—species unique to this region—make the Current River Hills a globally significant center of biodiversity, and this park is an excellent place to see that.

Photo by Ken McCarty

Though the Current River in its deep valley tended to protect the park land lying to its east from wildfire carried by west winds, there is evidence in the park of deep archaeological deposits suggesting as much as ten thousand years of human habitation, which would likely have provided a human source of ignition, accounting for the fire-adapted oak and pine woodlands in the area.

Early settlers raised livestock on the open range and also burned the woods to encourage forage. The greatest era of industrial logging in this area was from 1890 to 1920; the sawmill at West Eminence on the Jacks Fork some fifteen miles to the south, which began operations in 1909, attracted some twelve thousand people to the town. When the boom ended, settlers continued their tradition of burning woods to clear them for pastures until state and federal forestry officials made a concerted effort to end the burning, beginning in the 1930s.

Alton Box had initially acquired its land as a source of pulpwood for its operations, but managers soon realized the recreational values of the property were more important. They began protecting the regrowing forest. As a result, trees and understory are today more dense than they probably ever were before, and the glades have partially filled in with red cedar and elm. Park naturalists have begun reintroducing fire and restoring the landscape to a more natural condition.

State park officials planned to restore the Alton Club to its heyday from about 1938 to 1955. They talked of using the new park as a hub for a network of trails in the area, especially along the Current River and in the Roger Pryor Pioneer Backcountry just east of Route 19. They recognized that camping or lodging facilities would have to be limited, though, because of the rugged topography of the area and Scenic Riverway easement restrictions on more level land near the river. Planners considered draining a man-made lake upslope of the easement zone to allow room for parking, an amphitheater and multipurpose building, campsites, cabins, and an innovative “reciprocating wetland wastewater facility,” vegetated at the surface and with subsurface disposal. They envisioned a landing for canoes to pull in to visit the historic area.

Photo by Ken McCarty

Because the Alton Club property had been purchased with Conservation Department funds, the Missouri DNR agreed to allow hunting for a minimum of sixty days each year. Park officials had estimated the cost for initial restoration and infrastructure at some $7 million, money not available in the park division budget, so it would have to be raised privately or from special sources. One possibility was a monetary settlement then being negotiated by the state with AmerenUE in the wake of the 2005 breach of Ameren’s Taum Sauk Reservoir that tore the heart out of Johnson’s Shut-ins State Park.

Then in late 2007, in the interval between the announcement and the actual transfer—after MDC staff pulled out but before state park officials established a presence—a Shannon County road crew brazenly bulldozed a road from Route 19, beginning only a hundred yards south of the current entrance road, down a steep hill, and through the new park’s Jones Hollow nearly to the Current River. The road went through an area where park planners had intended to locate a group camp, through a fen and potential natural area, and part of the way in the creek bed itself, causing major damage. Stunned, park officials tried to block access, but within hours, a county crew reopened it. The issue of whether the route was or was not a legitimate county road was then referred to the attorney general’s office where it languished through an election, a change in administration, and the worst stock market crash since the Great Depression—the start of a devastating recession that would last years.

Thus the park remained gated and undeveloped, while the county continued blading the road. The state had few funds and little interest in investing in the park without resolution of the road issue, and planners talked increasingly about the difficulty of developing facilities and the expense of wastewater treatment in such a sensitive area.

With the road issue still unresolved, park officials finally talked with Shannon County commissioners in 2012 to see if some accommodation could be worked out. The result was the state conceding on the road, but the county agreeing to reroute it to avoid the most sensitive areas and to keep it gated during the summer season and at certain other times. That June, the park finally opened on weekends for day use, still without new development.

Then in 2013, word came that the US Marshals Service would be conducting an online auction of property seized in a drug raid—the old Camp Zoe property just east of Route 19 less than a mile from Current River State Park. Here was a beautiful 330-acre tract with some relatively flat land that had already been disturbed, some infrastructure already in place, and much of Sinking Creek with its fine sand beaches. It seemed the perfect answer to the vexing problem of developing camping, lodging, and other visitor service facilities on the steep, sensitive terrain of the Alton Club tract, and the money saved in development costs could more than equal the price of the additional land. So the state, through an agent, entered the bidding process and ended with the winning bid—though the marshals insisted on more, a total of $640,000.

Photo courtesy of Missouri State Parks

The purchase for state park use was generally greeted with favor, especially by former campers at Camp Zoe who had fond memories of their time there. Camp Zoe, named for the mother of one of the owners, opened as a girls camp in 1929, run by three teachers in Webster Groves and Kirkwood schools, so it early attracted many St. Louis youngsters, some of whom attended year after year. They enjoyed horseback rides to a swimming hole, sitting around the campfire at night, bunking in the screened cabins, and participating in all the other activities of camp life. In 1967 the camp was sold to two couples from the Ozarks, who began to admit boys as well as girls and operated it until 1986. After a period of intermittent rentals, a frontman for a rock band bought it in 2004, and they organized five or more weekends of jam-band festivals there annually, each attended by upward of seven thousand people, many of them teenagers. Federal authorities closed the festivals in 2010 after the owner pleaded guilty to “maintaining drug-involved premises.”

After the state’s purchase, park officials wasted no time in cleaning up the place, dismantling decrepit facilities, and planning for new infrastructure and visitor service amenities, including campsites, cabins, and a lodge. Only two significant buildings from old Camp Zoe remained, the stone and timber lodge on the hill and the barn in the valley, along with a local cemetery from the pre-Zoe era. Construction of road and visitor facilities estimated at $52 million began in early 2015, attended by controversy concerning the scope, speed, and secrecy of the project, expected to be complete in 2016.

Photo by Ken McCarty

How the plans for the Zoe property will be meshed with those previously made for Current River State Park remains to be seen, but the vision is to create a center for Ozark cultural and natural interpretation and recreation, including a staging area for long distance trails through the park, the Roger Pryor Pioneer Backcountry, and the Ozark National Scenic Riverways. Bluff-lined Sinking Creek is a perfect place for family fun in the water and for short floats. The Current River is right there for longer floats and fishing, and the old Alton Club is a fascinating historic complex. Round Spring, Montauk, and other beloved sites are nearby. Current River State Park, featuring the Current River and the Current River Hills, will no doubt become an unparalleled treasure.

CURRENT RIVER STATE PARK • SHANNON COUNTY ROAD 19-D AT HIGHWAY 19, SALEM

Feature image by Ken McCarty

Related Posts

The Diverse Current River State Park

The richly diverse Current River State Park has almost two miles of Current River frontage and a superb trail network. The fishing is abundant and a lazy float down the Current River is a perfect way to spend any day of the week.

Castlewood State Park

Castlewood State Park has more than thirty miles of hiking and biking trails, eleven of which are open to horseback riders. Experience the feel of a mature floodplain forest with its silver maple, box elder, black willow, white ash, sycamore, slippery elm, and hackberry. Bring a picnic and enjoy the beauty of this park.

Discover Southeast Missouri’s Hidden Gems

We searched every corner of Missouri for hidden gems—fascinating but sometimes overlooked places that are worth the drive. Where will this southeast Missouri hidden gems road trip, with places suggested by Missouri Life ambassadors, take you?

Seek Adventure in the Ozarks

Spend a day or two on the road and in nature on this adventure in the Ozarks. See elk and rivers and lakes. Float, swim, fish, picnic, and relax. Take a hike or rent a boat for the day. Be sure and stick around for a stunning sunset.