Once the personal retreat of an unconventional entrepreneur, Don Robinson State Park—one of the newest in Missouri’s state park system—offers a unique geological diversity and is home to an array of rare and unusual plants.

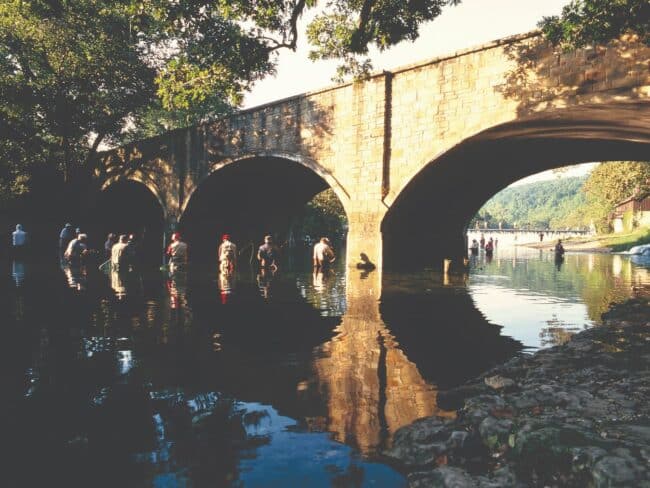

Photo by Allison Vaughn

In the rugged LaBarque Creek Hills, tucked away in the upper watershed of northwest Jefferson County, is one of the newest jewels in the state park system. Don Robinson assembled the 843 acres as his personal retreat over the years since his initial purchase in 1964, and then he willed them to the people of Missouri as a state park upon his passing in March 2012. With an estimated value of more than $5 million, the land is among the largest gifts in the century-long history of the system. Don Robinson joins the pantheon of state park heroes, another of those civic-minded individuals who had acquired special places of beauty and interest in Missouri and then donated them to the park system.

Robinson was struck by the ruggedness of the surrounding landscape when he bought his first 320-acre parcel in 1964. Fondly recalling his first visit, he explained, “It was so cold out the beer was freezing on top of the cans. I thought, well, this is really prehistoric—I just gotta get it.” As he continued to add adjacent parcels, he realized he was getting close to a tract the exact size of New York City’s famed Central Park—843 acres—and at that he stopped, though he continued to buy, develop, and sell property in the vicinity of his own retreat.

Photo courtesy of Susan Flader

Robinson was known for his utterly unique-yet-direct, humorous, and scrupulously honest personality. He made his money producing, marketing, and distributing a stain remover called Off, a concoction he made himself with simple equipment, first in rented space in Kirkwood, Missouri, with the assistance of local boys who kept their hours on the honor system, and later, in a room under the concrete deck of a raised swimming pool he built on his property. He was an early user of infomercials in the 1970s, producing and appearing in his own spots to demonstrate his product and paying television stations in Missouri and nearby states to run them. He thought nothing of loading up his station wagon with Off and driving to Iowa to stock the supermarket shelves himself. He also made an energy drink, Jyro Cola, which he distributed by truck with the help of local kids. Although he sometimes claimed he didn’t want neighbors, he was actually quite hospitable to a variety of friends and neighbors, interested in getting to know people, very well-read, and generous with the use of his land. In return, when he lived alone in the woods in his senior years, local folks watched out for him.

His home, where he lived alone for nearly half a century, sits on one of the most striking vistas of the park. He described it as “just a cut above camping—but I like it that way.” The lower stone portion of the house had been built in 1928, but he added a second floor and, later, a clerestory of his own design. The changes he made to the house and the surrounding landscape, including partial construction of a colonnade on the deck of the pool, demonstrated his interest in architecture and his frugal use of recycled materials and found objects; he even hired Kirkwood boys to chip terracotta ornaments off an old hotel being taken down in St. Louis. One change he never made to the house was adding a finished ground floor—the floor was literally the bedrock knoll on which the house sat. In 1997 an elaborate treehouse in his woods graced the cover of Smithsonian magazine, and several years later, the dust jacket of a hardcover book about outstanding treehouses. Sadly, it no longer survives.

Several intermittent tributaries of LaBarque Creek—French for “the boat,” a reminder of the French heritage of the St. Louis region— originate in the park. The creek flows six miles northeast to the Meramec River. With forty-four species of fish, it is considered one of the healthiest and highest quality streams in the St. Louis area, and its thirteen square-mile, steep, wooded watershed has remained largely undeveloped. Although the watershed is less than forty miles from downtown St. Louis and lies in the path of rapid suburban growth, it has been the focus of concerted efforts in recent years by public agencies, conservation organizations, and private landowners to protect its outstanding qualities, and nearly half its acreage has come into public ownership. Don Robinson’s land may have been the least disturbed, most beautiful of all, and he cared deeply about its future. As he put it, “I had to do something about it, or else my melon-headed cousins out of nowhere would come out of the woodwork and sell the place over a weekend or something.”

Photo by Ron Colatskie

The geology of the park and the LaBarque watershed includes outcroppings of limestone, dolomite, and sandstone that give rise to a rich mosaic of ecosystems. The St. Peter sandstone in particular, a formation that developed as part of the shoreline of a Paleozoic sea, has been sculpted by erosion over time into a variety of noteworthy features, including dry open glades and moist box canyons, cliffs, waterfalls, chutes, pools, and overhangs. The park has an impressive diversity of flowering plants, ferns, liverworts, and a fourth of all the moss species and nearly a third of the lichen species known in the state. There are also outstanding bird and other wildlife resources here, though more comprehensive surveys are needed. Indeed, much of the park is considered to have potential natural area quality. Given its complex geology and hilly topography, a visitor can hike through a range of ecological communities in an hour or two.

Several rare or unusual plants, including rock firmoss, Forbe’s saxifrage, partridgeberry, sensitive fern, and sphagnum moss, appear in several sandstone box canyons. The cliff walls and the flora that have taken root here. Rock climbing in particular is one of the biggest threats, as the lightest of tread can dislodge what little soil supports these delicate plants, leaving the walls devoid of plant life. Downstream from these canyons, rich moist forest unfolds, where thickets of spicebush, pawpaw, and other native flora offer a different atmosphere, and perhaps a glimpse of migrating warblers in spring and fall.

Photo by Ron Colatskie

Ascending from the shady environs of the box canyons, you will find a sharp contrast on the many dry glades. Sandstone glades are rare, and high quality examples such as those at Don Robinson State Park are even rarer, as the sensitive sandy soils are easily eroded. On these sites, gnarled blackjack and post oaks dot the dry sandy slopes, along with the occasional prickly pear cactus. In places, stunted and twisted eastern red cedars stand guard over the bare sandstone. These sandy, acidic sites harbor a suite of small plants adapted to these specific conditions, including rock spikemoss, fame flower, dwarf dandelion, and rough buttonweed. Glades perched on dolomite outcrops have a slightly different character. Here on the dry alkaline rocks and soils, wildflowers put on a colorful show throughout the summer months, with prairie dock, rosinweed, Missouri coneflower, glade coneflower, and the rare Fremont’s leather flower as highlights. These small glades are modest relative to open glade landscapes elsewhere in the Ozarks, but they are a special part of this landscape.

Photo by Ron Colatskie

The park’s woodland communities occupy a continuum between the strongly contrasting forests and glades. While not as open as the glades or as thick and lush as the forests, the woodlands reflect a smooth transition between the two. Here you will find stately white oaks and northern red oaks, and on drier sites chinkapin and post oak, over a rich understory of shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers. Historically, fire moved through these woodlands, creating an open park-like look. Perhaps set by humans over the millennia or ignited by lightning, these fires would burn through the woodlands before expiring on the moist, deeply shaded canyon slopes.

Restoring the natural role of fire is a priority for park staff and an important part of restoring the diversity of the park’s glades and woodlands. Over recent decades, fire had been suppressed as the countryside developed, and fire-intolerant species such as sugar maple began to creep upslope. Gradually, the park’s glades and woodlands became crowded with rank growth of trees and shrubs, shading out the ground flora. Luckily, many of these plants still found a refuge on thin soils, road sides, and in the occasional open field. As the park develops, ecologists will seek to restore these ecosystems to their original diversity of plant and animal life.

Photo by Ron Colatskie

Don Robinson’s unusually intact and scenic property has attracted naturalists for decades, some of whom became friends of his and returned repeatedly to survey its flora and fauna. The Webster Groves Nature Study Society has led botanical field trips here since the mid 1960s. The Missouri Native Plant Society, St. Louis Audubon Society, and Friends of LaBarque Creek Watershed have also highlighted the natural riches found here. Their attention helped to illuminate the potential of this property as a state park.

Development of this area will no doubt focus primarily on the stewardship and interpretation of its unusual natural history and scenery. Walking trails invite exploration of the rugged terrain and fascinating plant and animal habitats. Other public and protected lands in the vicinity, including several adjacent or nearby Conservation Department areas, offer much potential for cooperative effort in protecting the remarkable Missouri heritage of the LaBarque Hills region. The Friends of LaBarque took the lead in bringing various public and private entities and local landowners to the table to develop the 2009 LaBarque Creek Watershed Conservation Plan, which serves as a template for efforts in the area.

Don Robinson spent years considering what to do with his property and ultimately decided that Missouri State Parks would fulfill his vision of preserving this beautiful landscape for future generations to enjoy. On a peaceful knoll just a short walk from his former home, he rests for eternity, having become a part of the wild acres he so loved. Now his legacy is available for you and your family to enjoy as well.

DON ROBINSON STATE PARK • CEDAR HILL

Featured image by Ron Colatskie.

Related Posts

At Montauk State Park, a River is Born

Montauk State Park is one of the oldest in the Missouri State Park system. Visitors can see the headwaters that form the Current River, cast a line in a well-stocked trout run, explore a pre-Civil War mill, and maybe even spot a pair of bald eagles.

Cast a Line at Bennett Springs State Park

Bennett Spring State Park is well-known among anglers for its excellent trout fishing, but visitors also enjoy its hiking trails, Niangua River access, campgrounds, cabins, and meals served in the park's rustic 1930s dining lodge.

A Panorama of Wild Treasures at Taum Sauk State Park

A favorite of conservationists and Scouts, this hilly hideaway in the St. Francois Mountains features a number of special superlatives: highest mountain peak and tallest waterfall in Missouri, and one of the rarest plants in the United States.

The Diverse Current River State Park

The richly diverse Current River State Park has almost two miles of Current River frontage and a superb trail network. The fishing is abundant and a lazy float down the Current River is a perfect way to spend any day of the week.