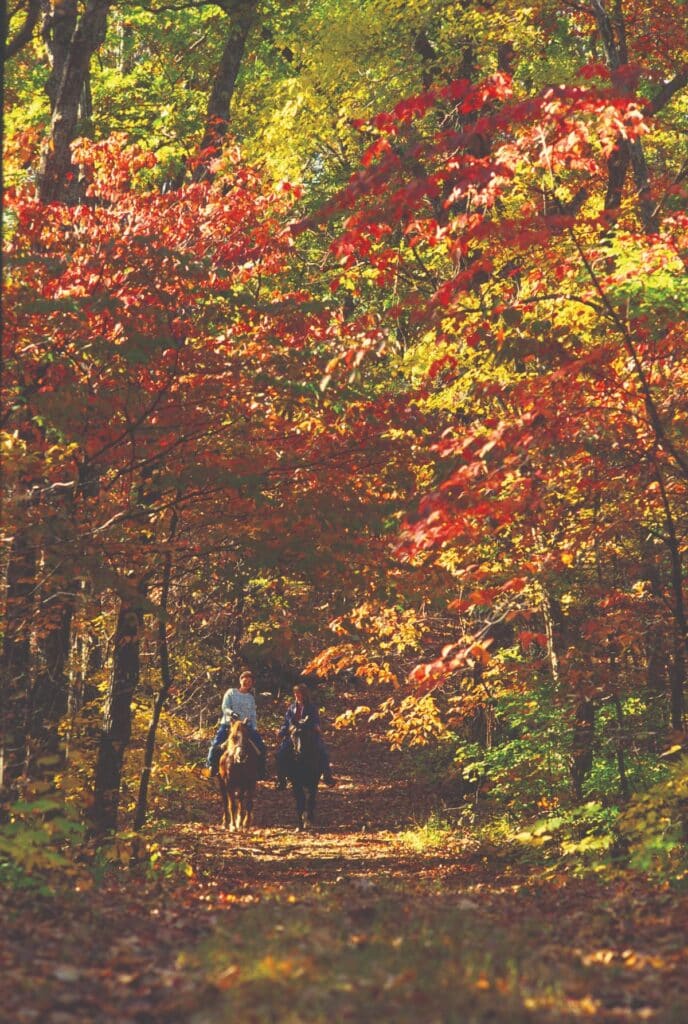

Sam A. Baker State Park encompasses 5,323 acres of lush wilds. Whether they come for the camping, floating, fishing, hiking, or horseback riding, outdoors enthusiasts find an abundance of beauty and a nostalgic take on park hospitality.

Photo by Michelle Soensken

On the southern flank of the St. Francois Mountains, Sam A. Baker offers visitors the freedom to wander at will in spacious, wild lands, savor old-time park hospitality in rustic comfort, enjoy the refreshing tingle of a clear Ozark mountain stream, and ascend the blue granitic hulk of Mudlick Mountain. Because Mudlick stands alone, separated from the concentration of domes surrounding Taum Sauk to the north, you can survey virtually the entire panorama of the St. Francois Mountains, while to the south and east you scan the deeply dissected hills of the Ozark border to the abrupt escarpment that drops off into the Mississippi Lowlands beyond.

This classic Missouri state park stands out in bold relief, encompassing all of Mudlick Mountain and the adjacent streams. On the east side, the park fronts on the St. Francis River and for about five miles on its tributary, Big Creek, which is an Outstanding State Resource Water. Huge boulders of Precambrian Mudlick dellenite, locally called blue granite, litter the hillsides and tumble into the canyons. The waters of the creeks rush and swirl around them, polishing them to a beautiful sheen.

Photo by Scott Myers

Because the park was established under the old Missouri Game and Fish Commission, a large portion of the mountainous area was initially set aside as a big-game refuge. Here, in scattered small plots, standing grain enhanced efforts to increase the state’s decimated deer herd, and a state turkey farm was established to help restore what was once an almost extinct species. In talking about the park and the wildlife when he was a boy, Gov. Sam A. Baker made it clear that he wished “to make available for this and future generations something that was commonplace to the youth of forty years ago.” Today, deer and wild turkey have returned to their former abundance, both inside the park and in the surrounding area, and no longer require artificial measures for their propagation. Jointly managed for decades by the Conservation Department and the old Park Board, Baker since 1981 has been entirely in state park hands.

Cultural as well as natural resources make this park a Missouri classic. The first major construction came during Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal when the park became the site of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp 5, set up in June 1933 in the valley near the present-day visitor center. By 1935, CCC enrollees had built barracks, installed telephone and water lines, laid out trails, planted trees, fought fires, and built a number of well-crafted rustic structures, including bridges, cabins, barbecue pits, restrooms, trail shelters, a gatekeeper’s stand, a stable, and the beginnings of a timber and blue granite dining lodge. After the CCC company pulled out in October 1935, Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers completed many projects, including the lodge.

Photo by Tom Nagel

Most of these handsome, sturdy, Depression-era structures continue to function in the park today. Indeed, they set the tone for the whole place. Many have been restored, and others will be. The dining lodge, formerly known as the Black Lodge because of the dark blue dellenite stone, is an evocative structure, as is the old stable with its three-story octagonal tower and two projecting wings, now converted to a visitors center. Mudlick fire tower, a distinctive CCC-era landmark, is still used to spot smoke in the region’s heavily timbered hills. Owing to the integrity of the preserved CCC and WPA workmanship, the entire 4,860 acres of the 1930s park has been designated the Sam A. Baker State Park Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

One of the best ways to enjoy Sam Baker is to hike the trail that begins across from the dining lodge. The trail descends first to the floodplain of Big Creek, hugging the base of Mudlick Mountain. To the right are the majestic sweetgums, sycamores, Shumard oaks, and cottonwoods of a southeast Ozark terrace forest; on the left is the rich vegetation of the shaded mountain base. The trail passes several steep rocky draws where huge purple and bluish boulders of the Mudlick dellenite are jumbled like a giant’s toy blocks.

Photo by Scott Myers

In the spring, these draws are alive with the rush of clear waters cascading over glistening rocks, moistening scattered patches of moss into puffy emerald cushions. These cool patches provide the rare and colorful four-toed salamander—a glacial relict species more common in Missouri during the colder climate of the Ice Age—with ideal shelter beneath which to breed and deposit its eggs. Later in the spring, the lower slopes of Mudlick display the lovely yellowwood tree, its luxuriant yellow-green compound leaves contrasting with fragrant pea-like white blossoms. Baker is one of the few places in Missouri to find this Appalachian species in its natural habitat.

Soon the trail turns left up a slope and begins a series of switchbacks across a bulging shoulder of the mountain. As the trail climbs, the forest soil gradually becomes thinner, rockier, drier. It then traverses several small glade openings filled with sun-loving grasses and flowers. From the openings, you may look back and see the valleys of Big Creek and, farther off, the St. Francis River. Reentering the oak sand hickories, the trail emerges suddenly at the brow of a point, where a small stone cabin seems to have grown right out of the mountain side. Its dellenite walls and floor, wood-shingle roof, and sturdy rock floor, you might notice that there is an open ledge not far in front of you. Step closer to the edge, and a spectacular panorama reveals the wild canyon of Big Creek, as you look upstream toward the cliff lined narrows and across at the pine-strewn slopes on the opposite bank. This shelter is one in a series of three strung out along the trail in an arc across the flank of Mudlick. Each is a joy. For a really special experience, you can arrange to camp overnight in one of them during the winter backpacking season.

This area is all part of the 4,420-acre Mudlick Mountain Wild Area, one of the largest wilderness preserves in the state park system, and a third of it is also a state-designated natural area. The twelve-mile Mudlick Trail, now a national recreation trail, contours around the mountain, with a spur to the fire tower at the top. Near the top of the mountain on its westerly flank are gnarled, stunted, weather-sculpted white oaks, many exceeding two hundred years of age and showing signs of the violent winds, lightning strikes, and heavy ice storms that pummel the mountain crest. Amazingly, most of the trees survive, providing numerous hollow trunks that serve as nature’s hotels for a variety of birds, mammals, reptiles, and invertebrate fauna.

Photo by Scott Myers

On the south ridge of the mountain, the trail leads through an area ravaged by a tornado in 1984. Hundreds of centuries-old oaks and hickories were toppled, just part of a never-ending natural sequence. Within two years, a profusion of flowering dogwood burst into bloom, because of the great increase in sunlight. The fallen trees and newly sprouted thickets supplied habitat for dozens of species. Today, the path of that tornado is hardly discernible to most hikers, though like all such events, it is recorded in the structure of the forest.

Sam A. Baker State Park is a great place for a family vacation. Its cabins and campgrounds offer a wonderful base of operations, its dining lodge a tempting respite from camp cooking. Big Creek is gentle and shallow enough for kids to play in, and the St. Francis River beckons canoes, kayaks, or rafts, which can be rented at the park store. The park offers six trails, short and long with varied loops and connectors, for hiking, biking, or horse riding. The nature center has hands-on exhibits, and the park staff offers great programs and guided hikes. Sam Baker would be proud of his namesake park and the authentic Ozark experience it offers Missourians.

WHO WAS SAM A. BAKER?

Life was hard in rural Wayne County where Sam A. Baker was born, grew up, and later taught school. The work of firing a furnace to pay for his board at the state teachers college in Cape Girardeau undoubtedly fired his determination to succeed. After working his way up from teacher to principal to superintendent, he became state superintendent of public schools and then in 1924 was elected governor of Missouri. During his term, many of the first-generation of state parks were acquired—not least of them the forested, mountainous tract of canyons, shut-ins, and rushing streams in Wayne County, close to the village of Patterson where the governor was born. Baker himself encouraged friends and relatives to sell or donate their land to the state beginning in 1926, and the first 4,000 acres cost the state only $23,000. The park later grew to more than 5,300 acres.

Featured image: The view looks south from Big Creek Glade across the creek toward the 4,420-acre Mudlick Mountain Wild Area, one of the largest wild areas in the state park system. The twelve-mile Mudlick Trail winds around the mountain.

Photo by Ron Colatskie

SAM A. BAKER STATE PARK • ROUTE 143, PATTERSON

Read more about Missouri’s amazing state parks and historic sites here.

Click here to purchase the Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites book.

Related Posts

Bison, Birds, and More at Prairie State Park

Natural prairie is the headliner at this state park, but the bison, elk, birds, and flowers are also stunning. Prairie State Park is a unique place, dedicated as a living tribute to a nearly extinguished native landscape.

The Beautiful Echo Bluff State Park

Echo Bluff State Parks has one of the most stunning lodges of any of the Missouri State Parks. And Sinking Creek’s crystal clear waters are a perfect place to dip your toes in or enjoy a gravel bar picnic. These are only a few of the outstanding attractions at Echo Bluff State Park.

The Diverse Current River State Park

The richly diverse Current River State Park has almost two miles of Current River frontage and a superb trail network. The fishing is abundant and a lazy float down the Current River is a perfect way to spend any day of the week.

Johnson Shut-Ins State Park

After one of the more cataclysmic dam failures in American history, Johnson Shut-Ins State Park has been reborn. The pools and rock slides are perfect for the whole family. There is an abundance of flora and fauna as well as hiking trails and the Black River Center.