With an aesthetic that’s equal parts Mick Jagger and Monticello, Kansas City-based interior designer Kelee Katillac has made an international name for herself as a creative force with a bold vision for historic preservation projects.

Photo by Karen Swope

When Kelee Katillac meets you, she may share that she sees an orange aura around you, or maybe it was red, or violet.

While you’re wondering what that means, Kelee is talking about how she’s spent the last few days, a recent photo shoot, a book signing event, working with wallpaper. What you immediately begin to see is not an aura, but passion, shining—sometimes burning—through her eyes, vibrating in her voice, and radiating from her face.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

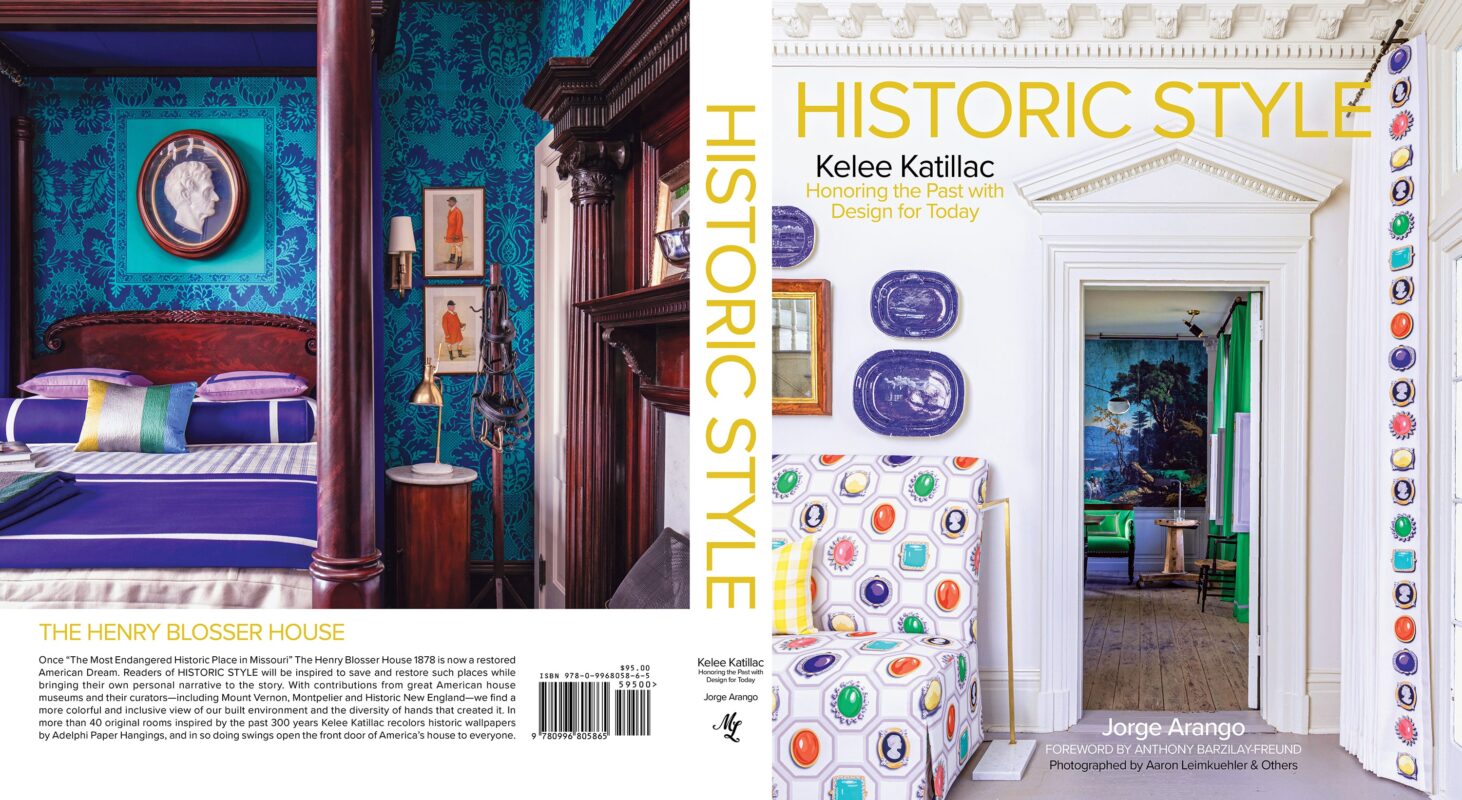

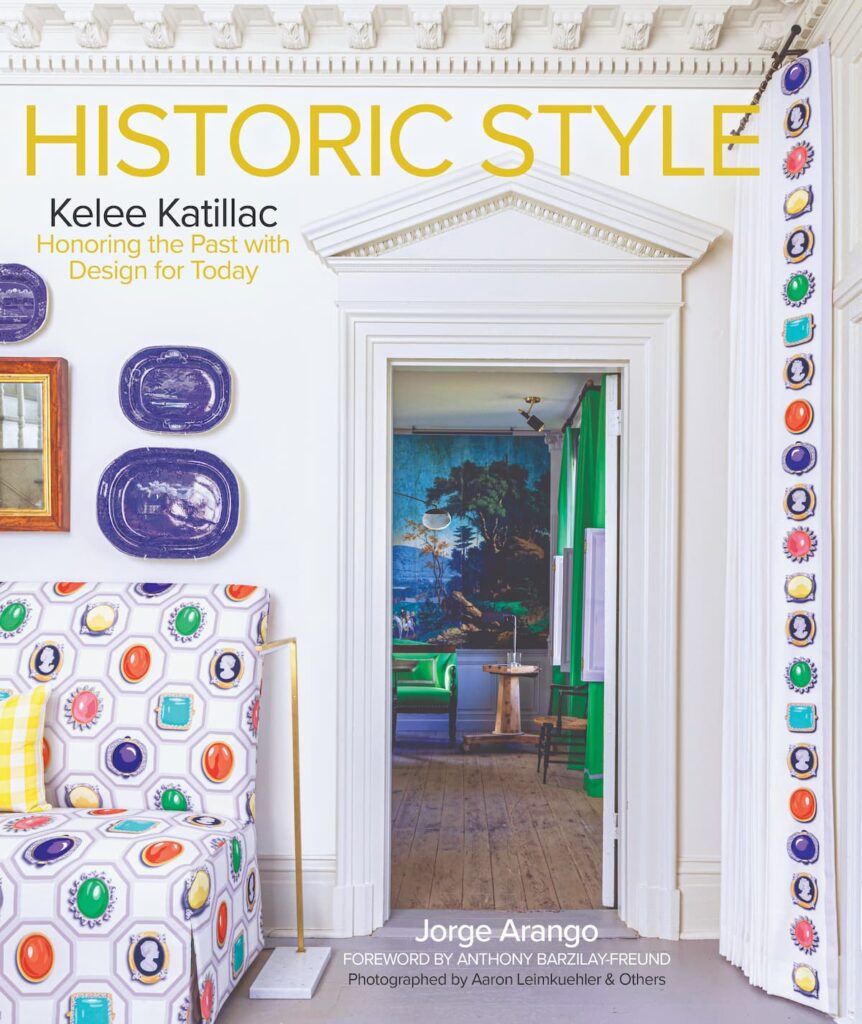

Kelee is the creative force behind the book Historic Style: Honoring the Past with Design for Today, and her passions are many: for preserving historic homes but making them livable for today, for honoring through her interior design the enslaved people who built so many historic homes, for splashes of color and patterns that enliven space, for horses and riding, for taking care of her ill husband, for small towns and communities, for bringing perfection to whatever she touches to the best of her ability.

You might expect Kelee to dress flamboyantly, but her attire sometimes reflects another side of her. Her slacks and jackets are often stylish but monochrome and conservative, suggesting a confident stillness. She moves quietly and without excessive gesturing. When questioned, she pauses to think and carefully chooses her words. You sense she spends a lot of time reflecting.

Many of Kelee’s passions are showcased in her new book, released a few months ago. The 360-page book documents the reformation of the Henry Blosser House just outside of Malta Bend, Missouri. Dr. Arthur and Carolyn Elman bought the Henry Blosser House when it was on Missouri Preservation’s most endangered properties list and seemed destined for demolition. The Elmans hired Kelee to reinvigorate the house and barn.

“Kelee is always thinking and thinking, puzzling things out until she gets the right answer,” says Carolyn Elman. “Her tenacity in thinking through the challenges, meeting the rules for historical preservation, and how to do that with style, was wonderful.”

Kelee expresses her vision for how to update historic homes without mindlessly recreating their historic appearance. An example is the dining room, where she incorporated a bright yellow inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and enlivened with orange accents.

“Kelee worked tirelessly to make the house reflective of my late husband’s vision,” Carolyn says. “She thinks in color, and she works 24/7, figuring things out. I often accused her of never stopping.”

In the book, Kelee also includes photographs and explains the inspiration drawn from famous historic homes, such as Monticello, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, James Madison’s Montpelier, and others. The book also showcases photographs from at least 40 of her other design projects.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

Jeff Herigon, owner of Hercon Construction, who worked with Kelee in preserving the Blosser House, says, “It was a surprise to me how much time she and her assistants spent on research into the historical aspect of every decision, every item. The time and legwork that went into those decisions was impressive, and it was fun to be involved in a historical project like this.”

That passion for getting the details right even went into the barn, which is one of Carolyn’s favorite aspects of the Blosser House property and where you will also find Kelee’s passion for horses—buying and selling them was an early business—as well as her design studio.

Kelee was raised near Bonner Springs, Kansas. Her maternal grandfather was a self-made man, as she describes him, a real estate developer and a gifted horse man, who founded a riding club in Kansas City, Missouri. At age two, Kelee would invite visitors to go to the barn to see her horse. She would lead them to a stall and proudly show off her stick horse. But soon she was riding real ones. At one time, Kelee competed in 40 horse shows a year. She grew up in a privileged but somewhat stifling environment, due to what she describes as a “fire and brimstone” church, more about judgment than love, which seemed to suppress her fun-loving and creative personality, she says. Today, she describes her faith as Christian Buddhist, or Buddhist Christian.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

Like her grandfather, Kelee is self-made. She was a shy girl, and she credits both horse showing and 4-H with training her in achieving goals, speaking, and leadership. She also used her sewing ability early to re-envision spaces.

“I found my calling as an interior designer in a sort of miraculous way,” Kelee says. “There was a moment in college when I became severely depressed. I lived in a mobile home instead of a campus apartment. Like most students, I didn’t have much money. I started sewing curtains and reupholstering cast-off furniture. I even reupholstered the walls. When I was doing interior design work, I felt like for the first time, life made sense. I felt like I was in harmony with life.”

That first experience while attending the University of Missouri in Kansas City captured visitors’ attention, and soon she was hired to remake their homes. One of her first major projects was for a client in the Union Hill District in Kansas City, Missouri. It was a Victorian Rowhouse kitchen that was featured in House Beautiful magazine. Since then, her work has also been featured in Traditional Home, Architectural Digest, Plaza Deco Sweden, and many other publications.

Soon she moved to New York City, where she landed a position with Ethan Allen on Fifth Avenue. She was living in the East Village with three roommates and dived deep into the counterculture movement, got to know the members of the Ramones band, attended poetry readings, met Allen Ginsburg and Dennis Hopper, and as she says, “had some wild times.”

She began reading 19th-century literature and studying the arts and crafts movement. Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s ideas about connecting art and nature captured her imagination. She soon found New York “confining.” She adds, “In New York, I would have had to climb the social ladder to keep progressing as a designer.”

She missed wide open spaces, the “groundedness” of people, horses, and “Nature with a capital N” in the Midwest and saw that she was getting further away from creating for herself. After two years in New York City, she returned to Kansas City, waited tables for six months, and then started her own design firm.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

She adopted her last name, “Katillac,” because of her love of music. Ahead of a Bruce Springsteen performance in Kansas City, a promotion gave away a pink Cadillac because of his song by that name. The winner lived around the corner from Kelee, who had moved to the Country Club Plaza. She loved Bruce Springsteen’s song and admired Elvis’s pink Cadillac, too. So she bought the car but used a French spelling with a “K” and a “T”.

With her new design firm, she wanted to test her theory that creativity in the home could influence a person’s well-being. That made her style eclectic, and she immediately attracted a lot of clients with her fresh, upstart style.

By 1996, she wanted to fulfill a desire to give back. She proposed doing workshops for Habitat for Humanity, to help new homeowners find their talents, learn the skills to “do-it-yourself,” and express their own styles in their new homes. She did a pilot workshop, and it was a huge success. She taught people how to make window coverings and reupholster furniture, which ultimately gave these homeowners a subtle new vision for their lives.

“Think about a chair on a curb. That might be perceived as a negative. But if you conserve it, replace the fabric, you’re shedding the old and creating a positive new vision for the future,” she says.

Soon, the Habitat for Humanity founders, Linda and Millard Fuller, asked Kelee to take the program nationwide. The workshops included other instructors as well as volunteer artists and talented Habitat community members that used Kelee’s curriculum. She did workshops across the country for three years.

“I was able to walk arm-in-arm across America with my Habitat friends. I bore witness to the challenges people of color still face today,” she says. She saw racial profiling more than once, when she would be riding in the back seat of a car driven by a black women and filled with black women except her. Officers would immediately release the car when they spotted Kelee.

Her first book, House of Belief, Creating Your Own Personal Style, included projects from the Habitat workshops, along with nine other case studies of her work for clients, including professional athletes and leaders of Fortune 500 companies. House of Belief was profiled in USA Today and on Oprah.

The Habitat work also inspired another passion. She desired to incorporate into her design work recognition of all of the people who built pre-Civil War homes. She wanted to represent the diverse hands that built America’s landscape. “People of color have not been depicted on fabrics, wallpapers, and in the design industry,” she says.

One example in the Blosser House is a photo of Major Charles Young, a buffalo soldier during the Civil War, staged in the gentleman’s bedroom. His uniform inspired elements of the window treatments. Another example in the book is in the Aderton House, her home in Arrow Rock, where she has hung artwork by Ken Gonzales-Day, in which the artist juxtaposes photographs of a circa 1520 Bust of a Young Man by Antico and a 1758 Bust of a Black Man by Francis Harwood. The piece asks viewers to ponder what makes these men different, if anything.

Kelee now more firmly than ever believed our homes heal us and shape us, and that jump-started yet another new passion, which was to design sacred places and a genuine sense of belonging in homes for kids. She and her husband, Steve Heiffus, founded Design Gives Back. Steve, who grew up in Grant City near the Iowa border, was a top architectural designer in Kansas City, and she and he had an instant connection. He volunteered with her Habitat for Humanity projects. They married in 2003.

They both had come to believe that the power of creativity could aid in healing for the critically ill. Kelee began doing “Miracle Makeovers” for children with cancer or other diseases that left children and their families with little hope. She turned the room of one child with sickle cell anemia, who had spent much of his life in hospital rooms, into a pizza shop that the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles inhabited with him, since he loved both.

She has many stories, some of which were published in Guidepost, about children who were given only three years to live, but lived seven, some who have recovered entirely, and others who simply have a higher quality of life, living with their disabilities. “What we can do for a room, we can do for our bodies,” she says. “Our Creator gave us the ability.”

This experience led to her second book, Rooms for Believing and Belonging.

Kelee saw this principle at work in the Blosser House, too. After Kelee began work on it, the owner Arthur Elman learned he had cancer. Kelee saw how the creative process, choosing the color yellow as a bold accent in the gentleman’s drawing room, for example, would pull him forward, give him a shot of energy. Kelee says the look on his face, as he was drinking a Negroni cocktail, sitting in the gentleman’s drawing room, was one of fulfillment.

He lived to see the fruit of his labors before passing away.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

Miracle makeovers could be described as the theme of the makeover of the Blosser House as well. Sherry Mirador, Kelee’s design associate, said the first day that she walked into the place, “I was like, ‘This place cannot be saved.’ What I saw was a house beyond repair. But in Kelee’s sight, it was savable. If anyone could do it, she could,” Sherry says. “She’s a creative genius.”

Sherry has immense respect for Kelee as a mentor too. “She has so much integrity. She would fight to stay within the historic elements but still be able to introduce design elements from the time the house was built up to the 2020s. I’m a seamstress by trade, and Kelee challenged me in ways I normally wouldn’t have challenged myself. Working with her allowed me to move beyond limitations I might have placed on myself.”

Kelee, age 63, and Steve, 78, had already moved to Arrow Rock after falling in love with the tiny historic town, before she began the nearby Blosser House project. Restoring it was an all-consuming, 10-year project.

Today, Kelee’s and Steve’s theory about creativity and healing is being put to the test most severely with Steve’s diseases, Parkinson’s and AFib. Steve fell ill as Kelee was working on Historic Style. He has good days and bad, and Kelee is his caretaker.

Photo by Aaron Leimkuehler

Kelee began working on the book immediately after finishing the Blosser House, and she says it’s the hardest thing she’s ever done, taking what she has learned and trying to communicate it in a way to help others. She also lived with the weight of trying to honor all of the people, the Blossers, the Elmans, and the diverse people who built the house, as she tried to stand in their shoes, feel their points-of-view, and do what she loves.

The last handwritten note from an interview with Kelee quotes her saying, “I think of Bob Dylan.” Nothing more. No context. Dylan didn’t make it into any of the design diaries found in most chapters. In these diaries, Kelee shares random thoughts, feelings, and her playlists, which include such diverse songs as Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” Edith Piaf’s, “La Vie En Rose,” Alanis Morissette’s “You Oughta Know,” Gregorian chants, and Frank Sinatra’s “Fly Me to the Moon.”

But for Kelee, Dylan’s “Forever Young” seems right: “May God bless and keep you always; May your wishes all come true; May you always do for others, And let others do for you.”

And her aura? We think we see all the colors.

Click here to purchase Kelee’s book.

Feature image by Aaron Leimkuehler.

Article originally published in the March/April 2024 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

Before & After: The Thompson House Restoration

The home built by some early northern Missouri settlers was on the verge of destruction when Ellen Dolan and a team of concerned community volunteers stepped in to save it. Take a look at some of these awe-inspiring before-and-after photos.

Order Now! Kelee Katillac’s Historic Style

Interior designer Kelee Katillac is widely known for her incomparable mix of color, couture, pop culture, and history. In Historic Style, Katillac reimagines what preservation can be with a renegade attitude and bold Mick Jagger style.

Zack Workman’s Barn Restoration

After retirement, Zack Workman wanted to focus on his art. First, he needed a workshop. He found the perfect spot in an old Sears and Roebuck barn in need of restoration. These before-and-after photos of The Barn at Greystone will amaze you.

New Cambria House Spans Centuries, Many Generations

Like most old houses, a two-story home built around 1890 in New Cambria has layer upon layer of stories—both the kind you tell and the kind you build.